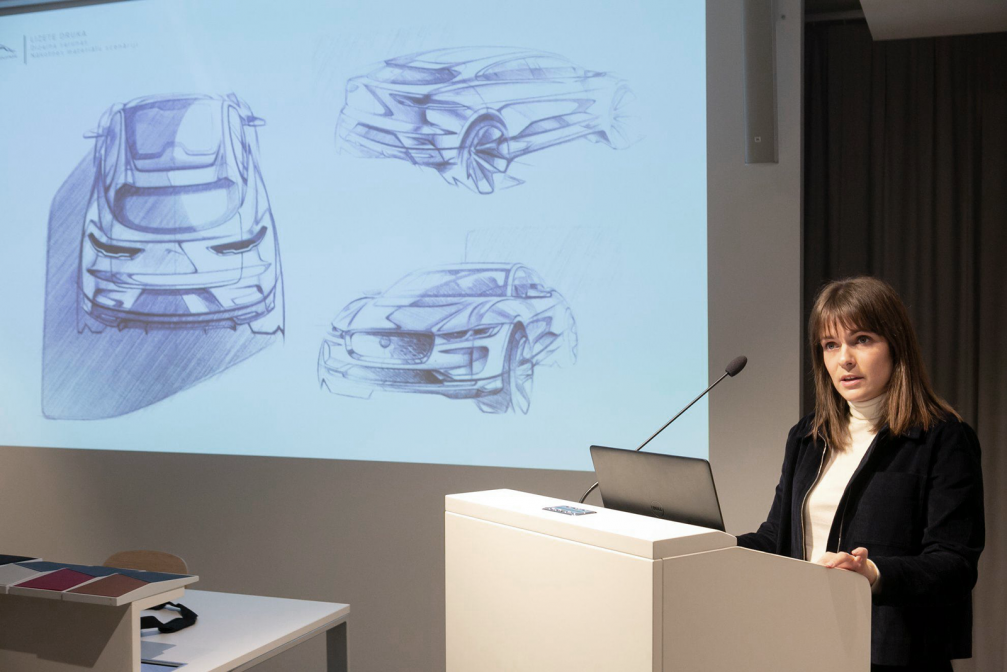

Lizete Druka is a Latvian-born designer who works as Design Experience Specialist in the UK-based Design Research team at Jaguar Land Rover, where she explores how the future is shaping the world of mobility. Having started her career in the Jaguar Colour and Materials team, Lizete brings a material-led perspective to automotive design. She kicked off the season of the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design talk series «Vārds dizainam» with a captivating presentation on future material scenarios.

How did you become interested in design?

Coming from a creative and scientific family I’ve always had an interest in the material world around us, from being obsessed with clay as a child, to learning how design can solve some of the most complex problems when studying for my undergraduate degree in Dundee. However, the moment I really became interested in design as a verb rather than a noun was after reading Malcolm Gladwell’s «The tipping point» in 2009. It helped me realise that everything is so connected and that design can have an emotional, human impact.

What originally made you want to explore the future of materials?

I have this obsession with touching stuff. Materials are everywhere. Especially when it comes to textiles, they are present with us from the day we are born to the day we die. Think about how textiles came about, what they represent and how they make you feel! Think about how simple, for example, knitting is. It is a technology that has existed for thousands of years, yet even today we are finding new ways to subvert it with new fibres, new technologies, and new applications. I think, particularly with regard to the future, we are at this really exciting point where we have to reassess all the material world around us, to really think what is actually appropriate for the future.

How does your work with materials fit into automotive design?

To bridge the gap from the future to today, I have been working to help understand how we can introduce more sustainable materials. In fact, there is no such thing as a perfect, totally sustainable material, there is only sustainable application; it has to be appropriate for its context. We are constantly researching and developing innovative materials for future contexts. It is getting much more sophisticated through processes such as life cycle analysis where you look at the implications of how something is applied, how it is manufactured, how it can be unmade. I look at every step of the design process, but material-led thinking is still very inherited in my approach. The material-led approach is about tactility and visceral experience. Especially in automotive, where a lot of innovations are intangible, the material world helps you to actually experience them in order to make sense of them. Materials tie it all together.

In automotive, we have to translate these really big questions about the future into something that can be emotionally resonant, tangible, and easy to understand. Facing big changes can be overwhelming. Maybe that is why I enjoy going to the Jaguar archive, as there is so much to learn from looking at the past through a modern lens.

What can we learn about the future by looking at the past?

In product design, there is a principle of «the most advanced yet acceptable». You see this a lot throughout the history. There have been examples when designers tried to take a leap so far forward there was no reference point, particularly when it comes to innovation and technology. We understand our world through our previous experiences. Step by step, in order to get to the future.

I think for us the importance of the Jaguar archive is the fact that we could have created the I–Pace model to look like a spaceship, yet we did well at balancing. It had historical cues to help us understand the concept; it feels familiar in a relatable way. Yes, there are points we are moving away from, but if we don’t look at the past, how will we ever learn? This is why even on our phones, the call icon still looks like a traditional handheld phone device. Or the trash can on the desktop… While we are going through revolutions, we still need things that ground us. As a designer, you have to take people on the journey with you. Sounds like an automotive pun almost! [Laughs]

As a designer, how do you prepare yourself for the future??

I am living in a constant process of learning. Maybe it is a skill in itself. I never had the patience to specialise in one particular skill; I used to stress being a jack of all trades and master of none. But I think being versatile and being able to jump between disciplines and, most importantly, having empathetic thinking is relevant, particularly when trying to design for the future.

Design and designers have to reinvent themselves. I feel like I live through constant phases. My most recent phase — last year I did a postgraduate certificate in Sustainable Value Chains at Cambridge University, where I got taught about how complex the move to sustainable future is and how to talk to people about environmental concerns. What I learnt was that you can achieve change and inspire change in others in a more systematic way — step by step, and not to eco-shame, which seems to be an emerging trend. We should not be too hard on ourselves. There is no perfect way to live.

Do you think designers should specialise?

No, I don’t think so. Being a designer, there is no way that you can master everything. At least in industrial design it’s very evident. There is a designer but it is a 3D modeller who will have to interpret a sketch to realise an idea; we have a whole team of incredibly talented craftspeople. They have tacit knowledge and years of experience with specific materials; they too influence the form and the use of material. By bringing different expertise together it becomes a meaningful collaborative process.

There is a beautiful essay written from the perspective of a pencil. To create this humble tool it took a lot of effort — hundreds of years of R&D by hundreds of people. While there is a desire in this extraverted world to seek recognition and affirmation as an individual, the reality, at least in industrial design, is that in order to create something you have to collaborate. And this is true not just in design, but even on a global scale — we know that we cannot achieve anything on our own. No wonder there are a lot of cheesy proverbs about teamwork. There is something in it! [Laughs]

As designers, we have to be much more aware of what’s going on. We have moved away from the designer being an individual. It is all about close collaborations now. We already have started seeing big companies joining forces, learning from each other. We will see this happening more often.

Another thing is the move towards mental health and well-being. Not just for individuals but also for the environment — to be present in the moment and experience it. In this context, it is interesting to think about the future of driving. Driving too could be a form of meditation in the right context.

No one knows for certain what the future holds. That’s why it is so important to look at different scenarios that could happen and build resilience for those. Regardless of what we will end up with, human beings are extremely resilient.

Do you think design will save the world?

What do we mean by «saving the world»? Do we want to continue living like we are today? Or do we need to take the approach that actually we need to design a better world in the first place? Buckminster Fuller famously said, «you never change things by fighting the existing reality, you change things by building a new model that makes the existing model obsolete». The past will save the future.

Viedokļi