In the picturesque Amata region, in the Gauja National Park, near the Stūķi cliff, there is Stūķi farm. Several years ago, a family saw the boulder ruins so characteristic of the Latvian landscape and decided to restore the buildings to their former glory. The renovation of both farmstead buildings lasted for seven years, and this year the project won one of the Latvian Architecture Awards, receiving praise for the atmosphere created in the building. The author of the project, architect Andra Šmite, shares her thoughts on the project.

The opportunities of working remotely have created a basis for more and more Latvian families to choose the countryside as their place of residence. During the pandemic, the desire to be closer to nature has become more pronounced than before, and I believe we can talk about a phenomenon of moving out of the cities. Young professionals settle in rural areas. In my circle of acquaintances — around Cēsis, Valmiera, and Kuldīga. Stūķi barn — a newly renovated home in the Amata region — belongs to a family that divides its time between Riga and Kārļi.

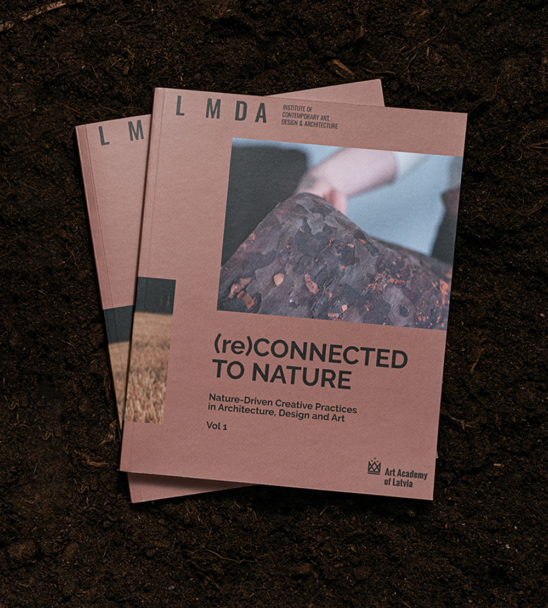

It’s possible that it is the pandemic that has created the «new rustic» trend in architecture and design, which symbolises the longing for an untouched rural environment and contact with nature. More and more designers and architects are asking the questions: «What are we creating? Why and how do we do it?» Work in the field of design and architecture now also includes social and environmental responsibility. In the Stūķi barn project, social responsibility manifests itself as respect for the material cultural heritage of Latvia, the construction methods and materials used in it. In my opinion, social responsibility is also the client’s desire to renovate a farmstead, while the extra money could be spent in other ways as well.

It was a common responsibility of ours, the architect and the client, to restore what was restorable and to do it in the best possible way. The year 1931 is drawn on the concrete above one of the entrances of the barn. I can only imagine how grand this farm must have been and what its owner was like if a building like this was built for cattle, not humans. A building that can be restored and inhabited by a family almost a hundred years later. I think that this could be a separate direction to be supported by the state — to provide assistance, at least in the form of a real estate tax discount, to those residents of Latvia who invest their funds in historic property restoration. Even if the building is not a listed architectural monument.

Although the Stūķi farm does not have an official status confirming its value, the landscape of Vidzeme is inconceivable without the long, stretched outbuildings, which are partially hidden between the wavy hills. The rusty auxiliary building also lies between the hills. In fall, its brown façade merges with the background of the golden autumn of Vidzeme. It seems important to me that the Latvian Cultural Canon finally includes landscape as well, and I catch myself asking the question — which of them is the most important and most beautiful to me? Is it the Daugava landscape, Zemgale plain landscape, Gauja valley landscape, Latgale lake landscape, Latvian forest landscape, seaside landscape, Abava valley landscape or the hilly landscape of Vidzeme?

Perhaps this house embodies the longing for an untouched countryside, which has become an unattainable dream for the average person elsewhere in urban Europe. It is not for nothing that this year’s Paris autumn design fair provided a significant place for the longing after the «new traditional» — being in nature in an uncluttered, natural and free environment, where the view through the window does not stop by the wall of the opposite house, but goes far. This direction includes new design thinking based on local material culture and heritage, where the place, the craftsman, the carpenter, the tradition and the material are the starting points for creating objects.

Undoubtedly, special places affect how things arise and what form they take. We have nothing to be proud of but what’s our own — authentic and local objects have value. The materials used in the Stūķi barn — wood, stone, lime, tar, forged metal and linen — are used to achieve a human-centered, modern, and local design. An essential part of the design of the Stūķi barn is the work of carpenters, blacksmiths, metal designers, potters, restorers, and handicraftsmen. I would especially like to praise the work of Latvian carpenters — in my opinion, we have a very high quality of carpentry, our artisans craft objects and details that are considered exclusive elsewhere in the world, such as solid wood drawers with dovetail joints, with ease and happiness. These are things that can also be called simply beautiful.

I think it’s important not to be shy to admit that beauty itself can be a value and a pleasure. One can be happy about how beautifully Latvian roses bloom, how light shines through the porcelain of Laima Ceramics, how the Mālpils wooden benches gray in the rain, and how a shadow is cast on the wall by the hooks forged by a blacksmith from Turaida. To rejoice as the grey stone after treatment with linseed oil shines like a loaf of freshly baked bread, as old boards can be rubbed almost white with green soap, and as the air smells of sprats when the shutters have just been covered with tar.

More about Andra Šmite’s projects — on the architect’s website.

Viedokļi