Spatiality of the Border — Rehabilitation of the Latvian Eastern Frontier is young architect Marta Ventere’s call to enrich the landscape of the Latvian eastern border by bringing human-centric architecture into it. Together with like-minded collaborators, Marta is developing an idea to build at least fifteen small hiking cabins along the border, inviting travellers to explore the unique region and meet the locals. Begun as Marta’s bachelor’s diploma work at RISEBA FAD, the project materialised this summer in its first realised cabin in Dagda. The initiative recently received the Latvian Architecture Award 2025.

«From a spatial perspective, Latvia’s eastern border critically lacks new, human-oriented spaces balancing the layers of military infrastructure that have accumulated over the years,» emphasises the up-and-coming architect Marta Ventere. This summer, she spent her weekends in Dagda, where, together with friends and locals, she built a small hiking cabin — the first of at least fifteen planned along the 450 km route tracing Latvia’s eastern border. Although the process was not without its challenges, Marta expresses fulfilment with what has been achieved, sharing genuine joy and gratitude for the helpfulness and warmth of the local people.

Healing the border through architecture

When considering her bachelor’s project, Marta knew immediately that she wanted to create something meaningful, not to work on the project as a mere formality. Each year, RISEBA FAD sets a conceptual theme for diploma projects; that year it was «blindspot» — a term describing what we do not see, do not wish to see, ignore, or fail to understand. Around the same time, there were intense public debates about constructing the border fence, which led Marta, together with her supervisor, architect Liene Šiliņa, to focus on exploring the border region.

Applying the university’s theme to the border area, Marta realised that in strengthening Latvia’s border security, the true «blind spot» had become the local inhabitants — their feelings and desires left unconsidered. A friend’s remark also stuck in her mind: «Latvia ends where the borderland begins.» This prompted Marta not only to study the territory from a spatial perspective but also to get to know the people living there.

The key question Marta posed was: how can architecture help heal the border? She stresses that it is only possible to answer this question after experiencing the place first-hand. «People there are determined, industrious, and strong. It became clear to me that my project should not be sombre. As she delved deeper into the concept of borders and read theoretical works about their hybrid and ambiguous nature, Marta realised that healing could not come from a single universal solution — what was needed was something local and specific, something that would not intrude on the landscape but could serve as a catalyst for development.

One of Marta’s sources of inspiration for the project was the research Transnational Monuments: In Search for a Universal Sacredness by Belgian architect and artist Cédric Van Parys, which explores water collection points — chesmas — along the Bulgarian–Turkish border. «These small-scale objects are not political; they are profoundly human. Anyone can fill their water bottle, chat with a passer-by, or simply sit in silence and enjoy the landscape,» explains Marta. «At the same time, they have spiritual meaning — they symbolise the borderland inhabitants’ desire to stay rooted in strong traditions and foundations to overcome the instability and anxiety of everyday life. In Latvia’s eastern regions, crucifixes serve a similar function.» Marta was introduced to this tradition by Staņislavs Maļkevičs, who restores crucifixes in his spare time and whom she affectionately calls the «dad of the Dagda project».

Another important source of inspiration was the Scandinavian hiking culture and its network of cabins available to anyone free of charge, provided they are treated with care and respect. «As these huts cannot be booked or reserved, travellers often end up sharing them with others, forming new friendships along the way. Eventually, I thought — why not create something similar here in Latvia?» says Marta.

Human scale and perspective in borderland development

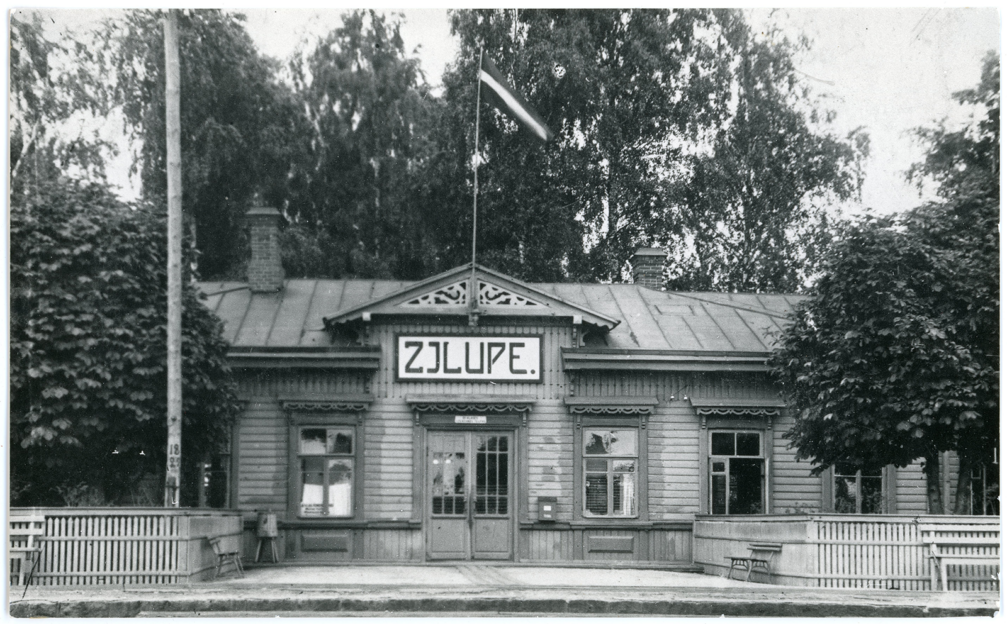

«The fence is necessary. That’s not in question. But when you go to the border, you see how brutally it is being built in some places — cutting through cemeteries and farms where people live. I think this process lacks balance, and the spatial environment should be developed not only for defence but also for people,» Marta emphasises. While researching, she was pleasantly surprised by newspaper articles describing the spatial development of the border region during Latvia’s first period of independence.

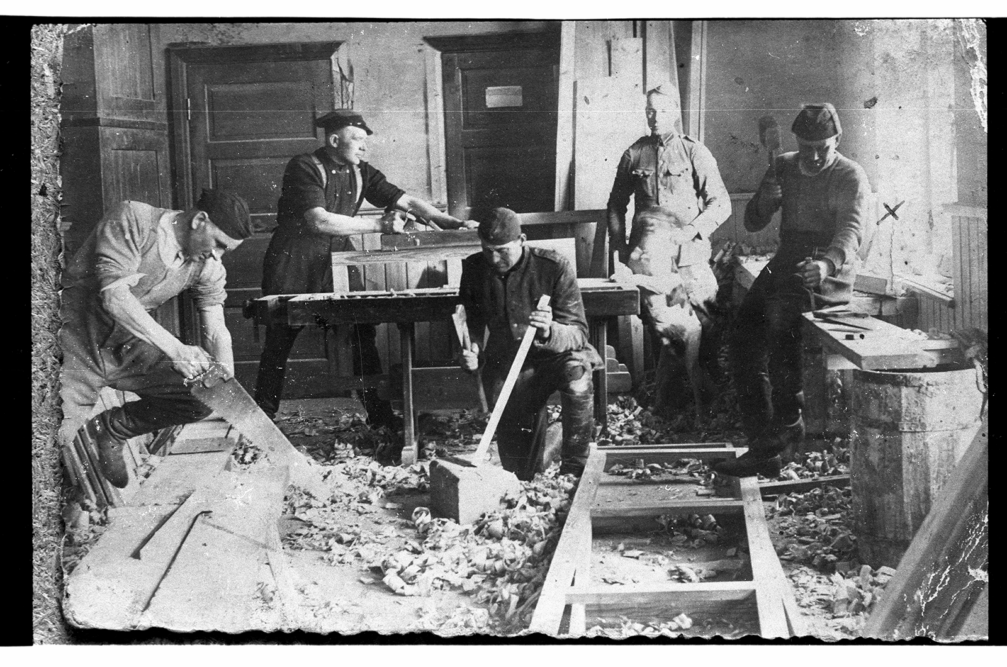

«Significant state funds were invested not only in military structures but also in building schools, churches, community and cultural centres, as well as in educating border guards. A 1937 headline in the Rīts newspaper mentioned that border guards were then called «beautifiers of life in the borderlands». They built and repaired houses with their own hands, maintained their surroundings, cultivated an understanding of good building culture, and inspired others, creating environments that could flourish alongside fences, watchtowers, and barbed wire. I believe that is exactly what the border area should be like today,» says the young architect.

Traces of that era’s legacy can still be found here and there in the border landscape. As different cultures have blended, a distinctive architectural and cultural heritage has developed — one that is unique not only within Latvia but also in a broader context. «Our goal in creating a hiking trail is to invite people to cross boundaries — to step out of their comfort zone and take the time to explore the border region, appreciating its culturally rich landscape and the sincere hospitality of its people. In doing so, we can bridge the divide between the border and the rest of Latvia,» Marta invites.

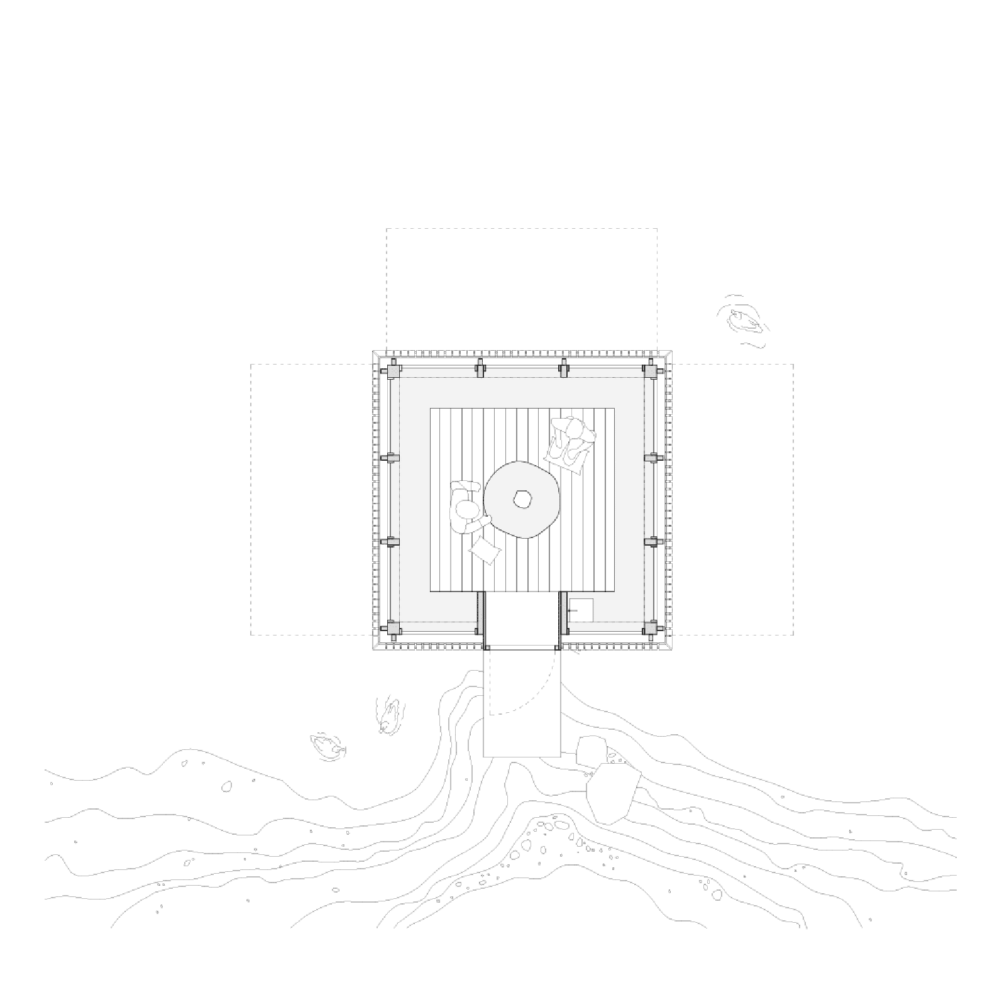

Her plan envisions a hiking route more than 450 km long along the border, with fifteen wooden cabins located roughly one day’s walk apart. They are intended to provide free overnight stays for visitors to the border region, while local residents could use them as meeting places, assigning them different additional functions — one might include a sauna, another could serve as a hunting tower or a ceramics workshop.

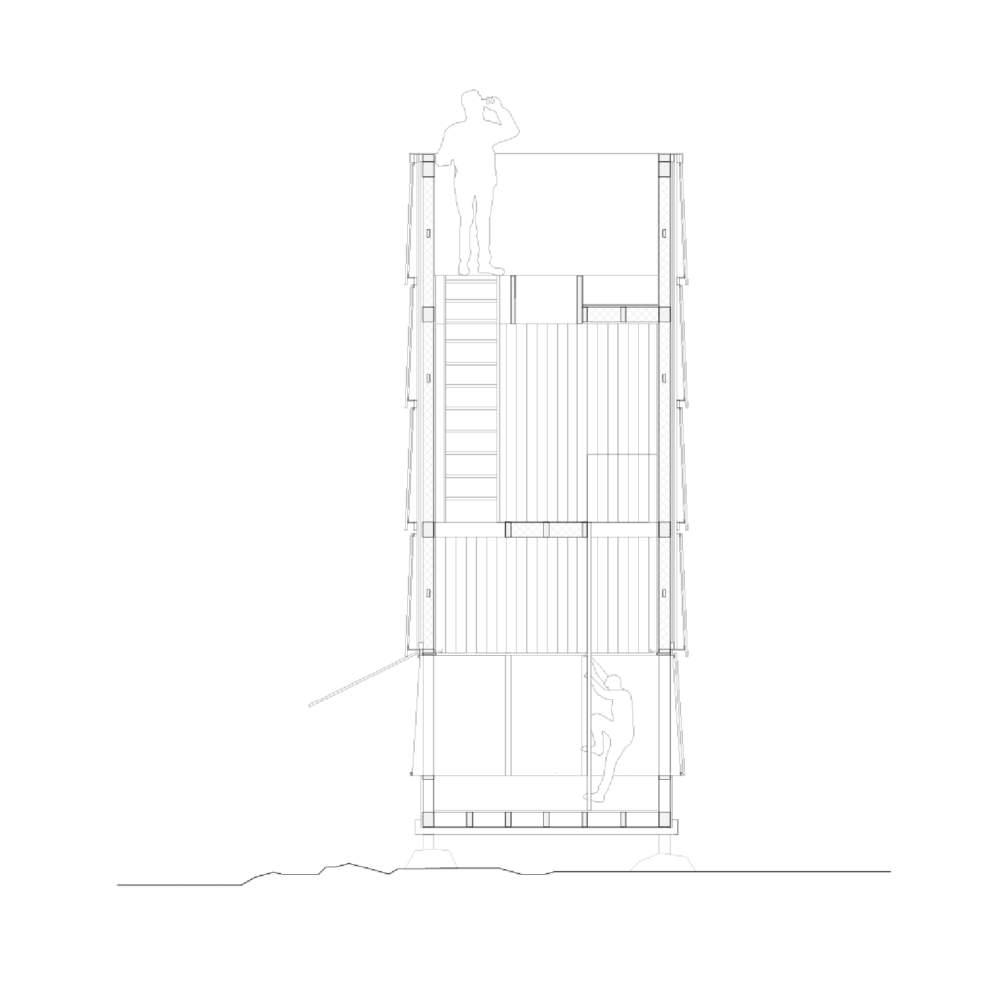

The cabins are to be built using traditional timber construction methods, employing wooden joints. The external form of the huts is inspired by the spatial structure of the border region. While travelling through the area, Marta observed that vertical typologies, like churches, chapels, guard towers, and grain dryers, dominate the landscape, which is why the cabin was also designed vertically. This allowed for the creation of a viewing platform on the roof, offering a broader view of the surrounding landscape. The area can also be explored by opening the shutters, which are installed on all four sides of the building. The viewing platform is reached through a circular hatch in the ceiling, symbolically marking the cabin as a point on the map. It is planned that each future cabin will incorporate a similar circular feature — a functional object such as a potter’s wheel, picnic table, or millstone.

Marta explains that through this project, she wanted to bring new life not only to the border region but also to the abandoned buildings visible in its landscape. The population in Latvia’s eastern border area continues to decline, and many properties lie deserted. Marta plans to use cladding boards salvaged from uninhabited and derelict buildings for the cabin façades. The available material will thus determine each cabin’s design, reinforcing their locality and diversity.

By creating infrastructure for tourism, it is possible not only to educate the public but also to provide an impulse for further development of the border region. The young architect is convinced that exploring this area would be interesting not only for Latvians but also for foreign visitors. The hiking route is designed to reveal various aspects of the border area and, in places, will approach the restricted border zone, accessible only with special permits. For this reason, some cabins are planned to be built directly near the border fence.

Building for people and with people

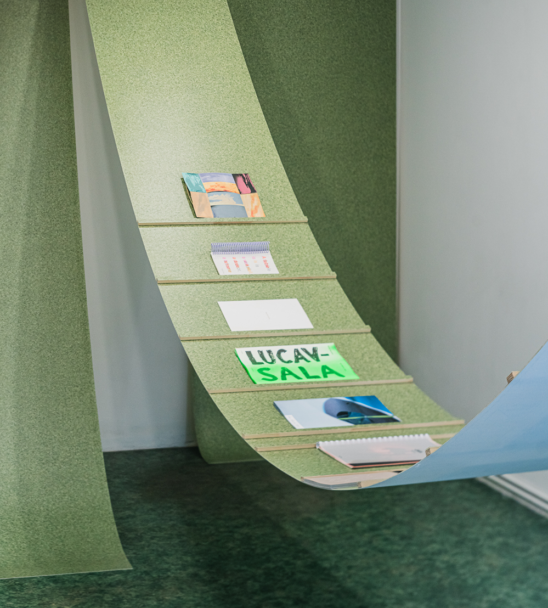

Marta explains that what began as research and a conceptual proposal quickly evolved into real action — it was actually members of the jury evaluating RISEBA FAD thesis works who first encouraged her to realise the project. With the support of the university and the State Culture Capital Foundation, construction of the cabin became part of the Dagda Architecture, Art, and Music Festival, organised this summer for the first time by architect Helvijs Savickis.

The pilot project proved to be an excellent learning experience, and the team already has ideas for improving and streamlining the process in the future. For most of the young architects and artists involved, it was their first hands-on construction experience — building something with their own hands gave the team immense fulfilment and a deeper understanding of design logic and architectural detailing. Invaluable support came from scenographer and carpenter Rūdolfs Bekičs, who taught the team how to work with wood, construct joints, and assemble structures. This summer, the main structure and façade of the Dagda cabin were completed, with doors and shutters installed. The cabin is now closed for the winter, and work will resume in spring to finish the details and interior.

Marta emphasises that even once completed, the cabin will never be a perfect, finalised project. She is fully aware that it will require ongoing care and small improvements over time. «It shows that the project is alive. It’s not something we can simply place there and forget. We know that, eventually, something will need painting or fixing. We’ll come back and do it!» The need for constant care also highlights how crucial it is to involve local residents in the project.

The first cabin in Dagda has already found its guardian — a neighbour, Igors, a beekeeper who used the unfinished structure to watch sunsets. A true craftsman, having built much with his own hands, he appreciated the design details such as the old façade boards and the boulders serving as the cabin’s foundation. As a gracious host, he helped the team out by donating old horse harness shafts — a suitable material for the stairs leading up to the viewing platform.

The cabin was originally planned to stand on four boulders, but moving them to the construction site proved impossible without help. Spotting some tractors nearby, the builders asked for assistance. Within an hour, entrepreneur Raitis Aizins and tractor driver Gunārs had organised everything and laid the foundation stones. Great support also came from the «dad of the Dagda project», Staņislavs Maļkevičs, carpenter and Krāslava Municipality deputy, who generously allowed the team to use his workshop and helped solve countless practical challenges.

Marta stresses that the people she met are among the project’s greatest values. When submitting the project for the Latvian Architecture Award, she was asked to indicate the construction costs — something difficult to define, as much was done seemingly for free, while the selfless work and help of people are, in truth, invaluable. «The core of our process is the human being. That’s why the construction involved not just a few individuals but a whole group of friends and colleagues — students of architecture, design, and art, as well as local residents. The experiences we gained while building just the first of the cabins could fill an entire book.»

Winning the Latvian Architecture Award 2025 came as a complete surprise — and Marta is particularly pleased that the project was recognised and understood by members of the international jury as well. The team hopes that this recognition will give new momentum to the project’s development and that next summer even more students from different disciplines, as well as craftsmen and masters willing to share their knowledge of traditional building methods, will join the process. Marta and her collaborators are now seeking supporters to establish their own studio and workshop that would enable the continuation of the project.

Viedokļi