Until the end of the year, the Latvian War Museum is hosting the exhibition A Child’s Mind, opened last year and dedicated to children’s experiences of war. The museum describes it as one of its most courageous and emotionally powerful projects in recent years. The exhibition offers a platform for parents and children to engage in open conversations about complex and sensitive topics, including war, violence, and mechanisms of survival. The creators of the exhibition chose an approach centred on sensory experience, which young visitors can encounter through the play stations designed by the young design studio .obj.

Displayed on the ground floor of the Latvian War Museum, A Child’s Mind sheds light on the impact of warfare on one of the most vulnerable civilian groups — children. Its aim is to reveal the destructive reality of war through the lens of a child’s perception, showing how armed conflict and associated violence affect children’s emotional and psychological worlds, as well as their attempts to understand and interpret what is happening around them. The exhibition presents the individual experiences of six children, giving voice to their stories of displacement, life in camps, hiding, sexual violence, and other traumatic events. These narratives unfold through text, documentary video and audio materials, and a range of objects. Among them are a fabric Star of David that Jewish people were forced to sew onto their clothing in German-occupied Latvia, teddy bears that accompanied children during forced displacement, and a young girl’s coat made from blanket scraps in the Salaspils camp.

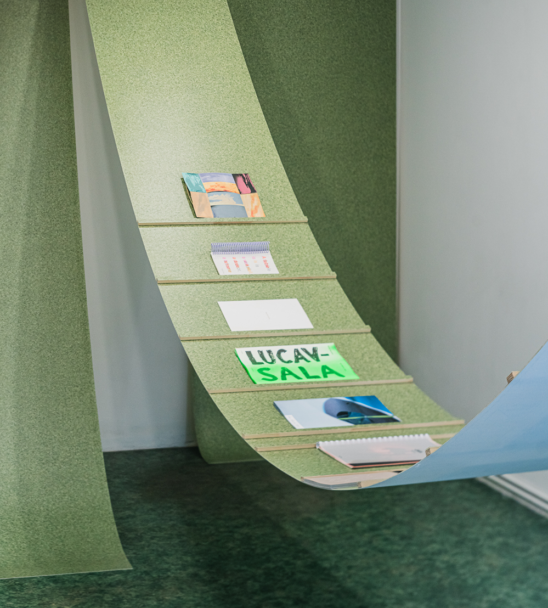

The exhibition is aimed at both children and adults, offering two parallel yet interconnected flows of information. How can an exhibition be made accessible, understandable, and engaging for such different audiences? This was one of the greatest challenges faced by the designers, Elīna Lībiete and Ivars Veinbergs, founders of the design studio .obj. Elīna notes that much thought was also given to the question of «what the role of a museum is at a time when all traditionally museum-based information can be found on Wikipedia». The creators of the exhibition sought to answer this by offering visitors an emotional, atmospheric, and bodily experience. Designers highlight the successful collaboration with child psychiatrist Ņikita Bezborodovs, who consulted the creative team and provided essential support in understanding child psychology during the early stages of the project.

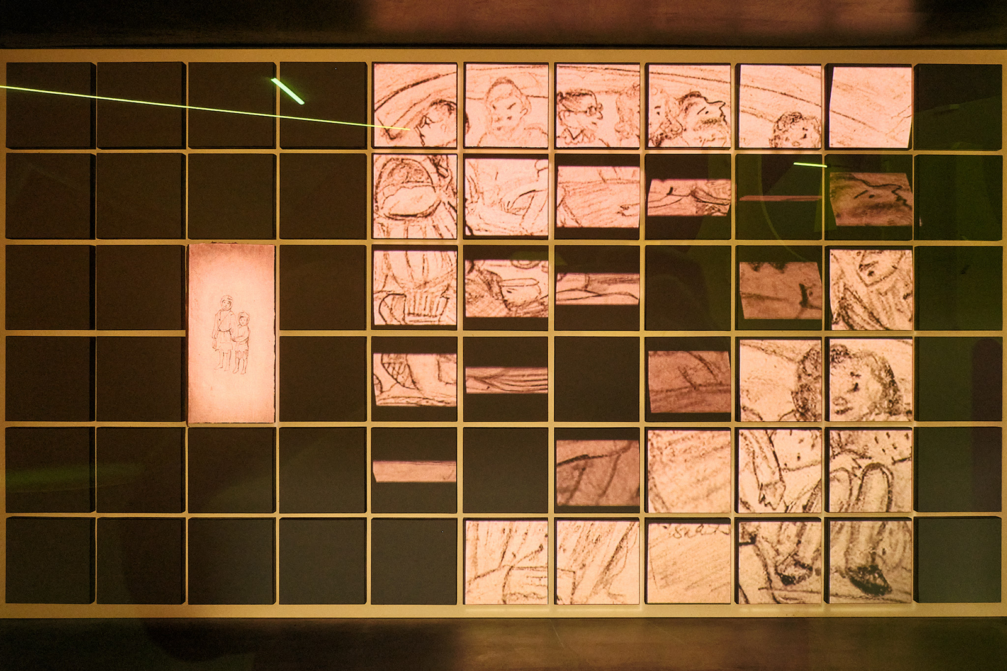

Due to the specific nature of children’s perception, even wartime conditions can be experienced as a form of play, fundamentally different from an adult’s viewpoint. This understanding is reflected in the exhibition itself, where documentary reality is combined with play areas designed for young visitors. A child’s ability to fantasise and play serves as a protective mechanism, shielding the mind from the horrors and fears of reality.

From the outset, the exhibition’s creators agreed that its core would be an invitation to experience specific emotions. For adults, this is achieved through historical narratives that provide full context; for children, through cleverly designed play stations and conversations with their parents. Documentary materials are positioned so that they are largely inaccessible to younger visitors. How much of the six stories to reveal to a child, in what way, and with which words is a decision left to the accompanying adult. «The ideal scenario we were aiming for is one where the parent listens to the story while the child next to them plays out the corresponding emotion, and then they talk about it together,» Elīna explains. She hopes the exhibition will encourage intergenerational communication and help adults explain historical and contemporary events to children in an understandable and emotionally sensitive way.

The designers have observed that children eagerly engage with the proposed activities, yet the exhibition is no less emotionally intense for parents. They watch their children, raised in times of peace, at play while reflecting on the content of the exhibition. Each play station contains a kind of catch — an interactive element, an unexpected technological solution, or a hidden idea. In the area with human figures inviting visitors to «dress up the freezing», children discover that it is impossible to fully cover them, as there are not enough clothes for everyone. This activity resonates with the touching story of the little coat.

Wartime presents a paradox: threats of death, which adults clearly perceive as danger, may appear to children as an exciting game. The remnants of war — warehouses, ammunition, and weapons— can be seen as mysterious and attractive toys. At the part of the exhibition titled Curiosity, the focus is on dangerous games involving unexploded shells or other wartime objects found on the ground, which became part of Latvian children’s post-war reality. This theme is complemented by the game Don’t Touch It. It consists of a board and several dice marked with numbers and ominous symbols that the child is encouraged not to touch. If temptation proves too strong, the forbidden game is played and the dice are thrown onto the board, where sensors hidden beneath may respond with a rumbling sound. Sometimes they activate, sometimes they do not — much like real life, it is a game of risk.

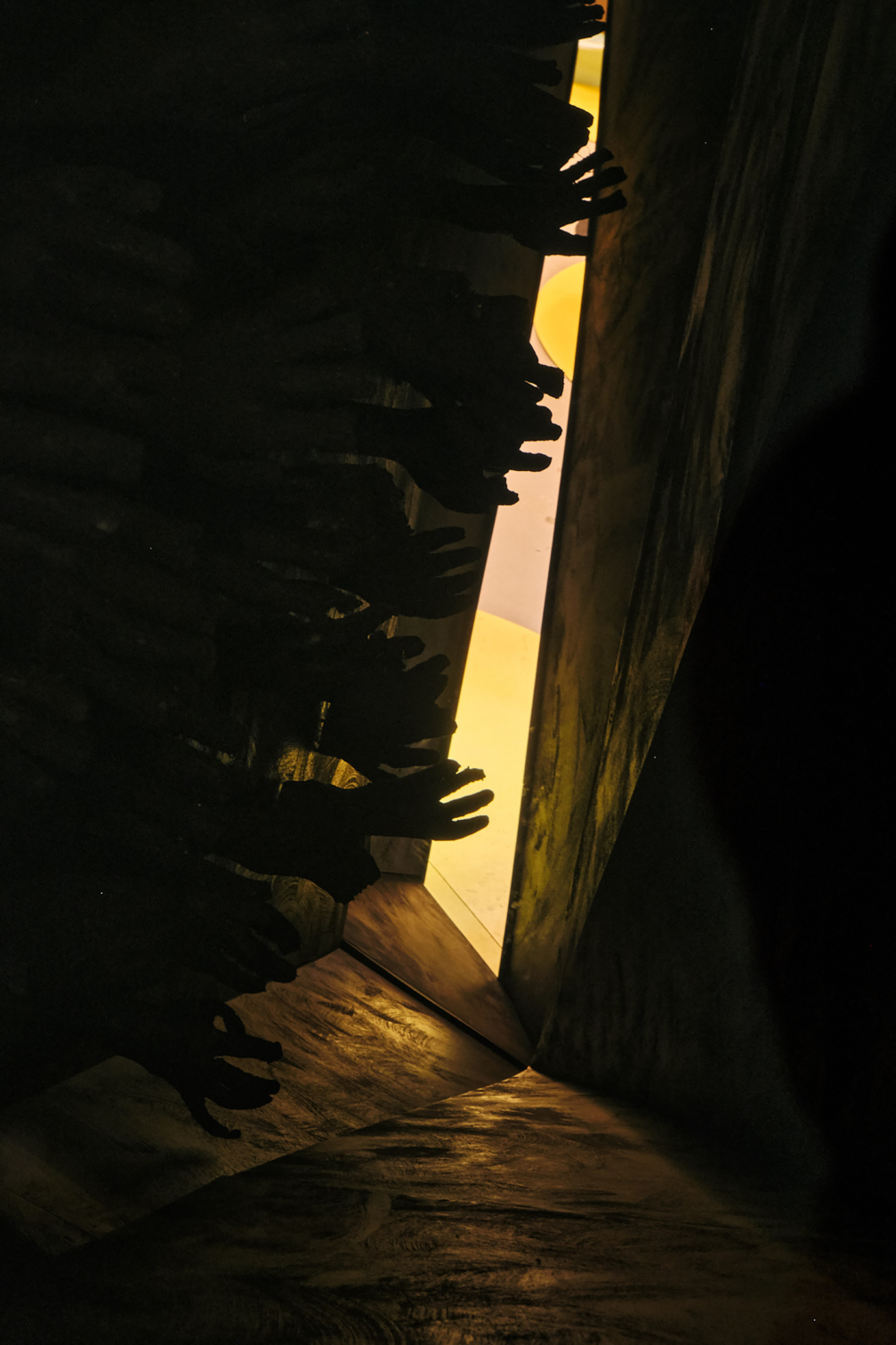

Responding to the prompt «Be as quiet as a mouse!» at another station also proves difficult, as the castle-like installation amplifies every sound made by the child. This serves as a metaphor for how vibrations and disturbances interfere with building dream castles, just as military conflicts disrupt plans, expectations, and hopes. «We tried to reveal the stories through emotional and bodily means. At one station, an adult must symbolically stand beneath planks, as if hiding, while the child plays in the nearby castle with the task of staying quiet. We noticed, however, that children mostly make noise deliberately, because interacting with the castle equipped with microphones is fun. This adds another dimension to the adult experience, making it clear how difficult it is to silence small children in a crisis situation when hiding is necessary. At the same time, through play, we wanted to give children the opportunity to experience a reflection of these emotions in a safe environment and on a small scale — emotions that are present in the historical artefact stories,» Elīna explains. The only exception is memories of sexual violence, which are not accompanied by activities and remain solely within the «adult world».

Visually, one of the key motifs of the exhibition design is contrast — the collision of two different worlds. «The aesthetic of the information flow intended for adults is rough, dark, sharp, and minimalist, while the children’s world is light, playful, and gentle, with rounded forms — abstract, yet sufficiently rich.» The gloomy polyhedrons housing content for adult visitors appear as foreign bodies intruding into the sunny environment of childhood days. They serve as reminders of the indelible marks and traumas that wars and related experiences leave on future generations. At the same time, a child’s mind is remarkably emotionally resilient, and in the exhibition design, playfulness and light ultimately prevail.

A Child’s Mind reminds us that war is not only a political or historical phenomenon but also a deeply personal and emotional experience, especially for children. It offers an opportunity to reflect on the past, to assess contemporary conflicts, and to ask questions about society’s responsibility in protecting children — both historically and today. The exhibition also marks a turning point in the way the museum seeks to shape public understanding of the impact of war. «Data compiled by UNICEF shows that in 2024, one in six children worldwide lived in conflict-affected areas. At the Latvian War Museum, we have clearly defined our aim to change how we talk about military conflicts. Traditionally, these have been stories told from the perspective of winners or losers, highlighting the experiences of commanders, politicians, and soldiers. We want to give a voice to those whose stories have not been heard before, and to talk about how war affects and transforms society. One exhibition cannot protect us from military conflicts, but I believe it can be the beginning of a path towards greater public understanding and participation in the defence of our country,» says Kristīne Skrīvere, director of the Latvian War Museum.

The exhibition was created by the Latvian War Museum and the Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia. Creative team: historical research, concept, and texts by Klāvs Zariņš and Maija Meiere–Oša; conceptual execution and texts by Kaspars Eglītis,; multimedia director Roberts Rubīns; designers Ivars Veinbergs and Elīna Lībiete (design studio .obj); child psychology consultant Ņikita Bezborodovs; curators Elizabete Palasiosa and Marta Kontiņa (Story Hub).

Viedokļi