Architecture is like a language — its power arises, and its meaning changes, through use. To explore how different space-makers understand inclusive and safe spaces, artist and designer Liene Pavlovska spoke with interior architect and artist Maike Statz, architects Arnita and Kārlis Melzobs from the studio Gaiss, architect and visual artist Pauls Rietums, and the artist duo Paula Veidenbauma and Diāna Mikāne, who work together as the collective Gel.office.

While studying at the Studio for Immediate Spaces programme in the Interior Architecture department at the Sandberg Institute, I went on a research trip to Berlin. By a happy series of coincidences, my friend and I were able to visit a residential module in Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation. The apartment owner, an enthusiastic architecture fan, was delighted to show us its details. The building was designed as a self-sufficient organism, where residents could spend their time developing their creative potential. Next to the apartment entrance was a special hatch, allowing delivery workers to leave milk, bread, and newspapers without direct contact with residents — unseen, like shadows. The building was conceived as a complete microcosm, so that in an ideal, utopian scenario, its inhabitants would have no need to leave the comfort of their own walls.

The way an employer treats those doing seemingly «lower» work reflects the value system of a company or institution; likewise, the space allotted to the people who perform the work of maintaining and sustaining everyday life speaks volumes about the architecture itself. Early in my creative career, I supported my practice by working in various cleaning jobs. This role was a little like being a secret agent — I had to be invisible, often working at night or in the early morning. As a cleaner, I experienced spaces in a tangible and tactile way, and through these encounters, the patriarchal nature of space and socio-economic inequality often became apparent.

The visit to Unité d’Habitation and my experience as a cleaner became one of the driving forces for my master’s research, which sought to uncover and examine how architecture — as I had personally experienced it — has influenced, or can influence, personal and collective events. What is the power of architecture, and what are its limits? I explored this in conversations with other space-makers whose practices embrace sustainable, inclusive, and critical approaches to architecture.

What, in your opinion, is inclusive architecture?

Gaiss:

Inclusive architecture can be understood by anyone; it requires no manual. Regardless of abilities, everyone should be able to enter through the same doorway comfortably, without assistance, without having to follow specific instructions. In our work, the entrance is a crucial starting point for inclusive architecture.

One of our boldest proposals was for the 2010 competition to renovate the Latvian National Museum of Art, in which we suggested cutting through the historic staircase so everyone could enter the museum through the main entrance.

Maike:

Inclusive architecture centres the creativity, needs, and desires of those who have historically been marginalised or made invisible in space and space-making practices. I’m particularly drawn to the term «unruly bodies», which I first heard used by activist and architect Jos Boys, to describe bodies that don’t conform — queer, disabled, elderly, neurodivergent, or children, for example. These are bodies often treated as exceptions in spatial design. Inclusive architecture creates conditions where such bodies have agency. It doesn’t prescribe how space should be used, but allows for adaptation, fluidity, and difference. I don’t believe any single space can meet everyone’s needs, but inclusive architecture shifts who is centred in the design process. It challenges the assumption of a normative user and asks who is given the power to shape space in the first place.

In 2023, I co-curated Dissident Publics with the collectives Exutoire and Nogoods. It was a co-creation project exploring the social and spatial potential of public space from queer and intersectional feminist perspectives. Public spaces can be sites of exclusion or threat, particularly for LGBTQIA+ communities. Through collective workshops and prototyping with a group of artists and architects — Léa Brami, Mahé Cordier-Jouanne, Lexie Owen, Liene Pavlovska, and Jan Trinh — we reimagined how public space might affirm rather than suppress difference. The resulting installation was both a spatial proposition and a platform for public events led by local queer practitioners.

I think the term «inclusion» itself also deserves critique — it can imply that some people are already inside, and others are being invited in on certain terms. Truly inclusive architecture rethinks those terms altogether.

Pauls:

Inclusive architecture is well aware of its users, it recognises that it makes mistakes, and is ready to change.

And how does sustainable architecture manifest itself?

Pauls:

The most concise way to describe it is to see architecture not as an object, but as an extended slice of time. The thoughts and understanding of sustainability in architecture are evolving quickly and constantly. When I began studying, the trend was to teach about passive houses — hermetically sealed, highly regulated new buildings with minimal energy loss. By the time I finished my studies eight years later, my tutor Charlotte Malterre–Barthes was urging a complete rethinking of the architect’s profession and the necessity of building anything new in Europe at all — instead suggesting we focus on restoration, maintenance, and securing dignified living space for all through changes in legislation. I find it exciting to imagine how we’ll think about sustainability ten years from now.

Maike:

I see sustainable and inclusive architecture as closely linked. Sustainability isn’t just about environmental impact — it’s also about how a building relates to its social and material context. Sustainable architecture works with what already exists, rather than relying on novelty or extraction. It values reuse, repair, and adaptation.

I’m especially interested in how care and maintenance are incorporated into design. Architecture often focuses on a final form, with little thought for how a space will be used, supported, or sustained over time. Truly sustainable architecture considers the people and systems that tend to it — cleaners, caretakers, communities — as integral, not incidental.

Gaiss:

For us, sustainable architecture means responsible use of resources — prioritising reuse, care, and repair before creating something new. For example, in our work on the Lielvārds office, we exposed the building’s structural shell and service systems to make its future adaptability clear. The office is located in the Valdemāra Centre, a building that might seem aesthetically outdated in today’s context. We see value in working with such buildings, giving them a new visual framework and making them more pleasant. Our goal was to create a contemporary, comfortable workspace that revealed the building’s potential. We deliberately exposed the reinforced concrete shell, with its striking column capitals that reveal the building’s structural logic, and highlighted its existing qualities. The service systems are visible, separated by lightweight partitions — this clarity and openness allow the space to be reconfigured and adapted to changing working patterns and needs, ensuring it remains in use for a long time.

Gel.office:

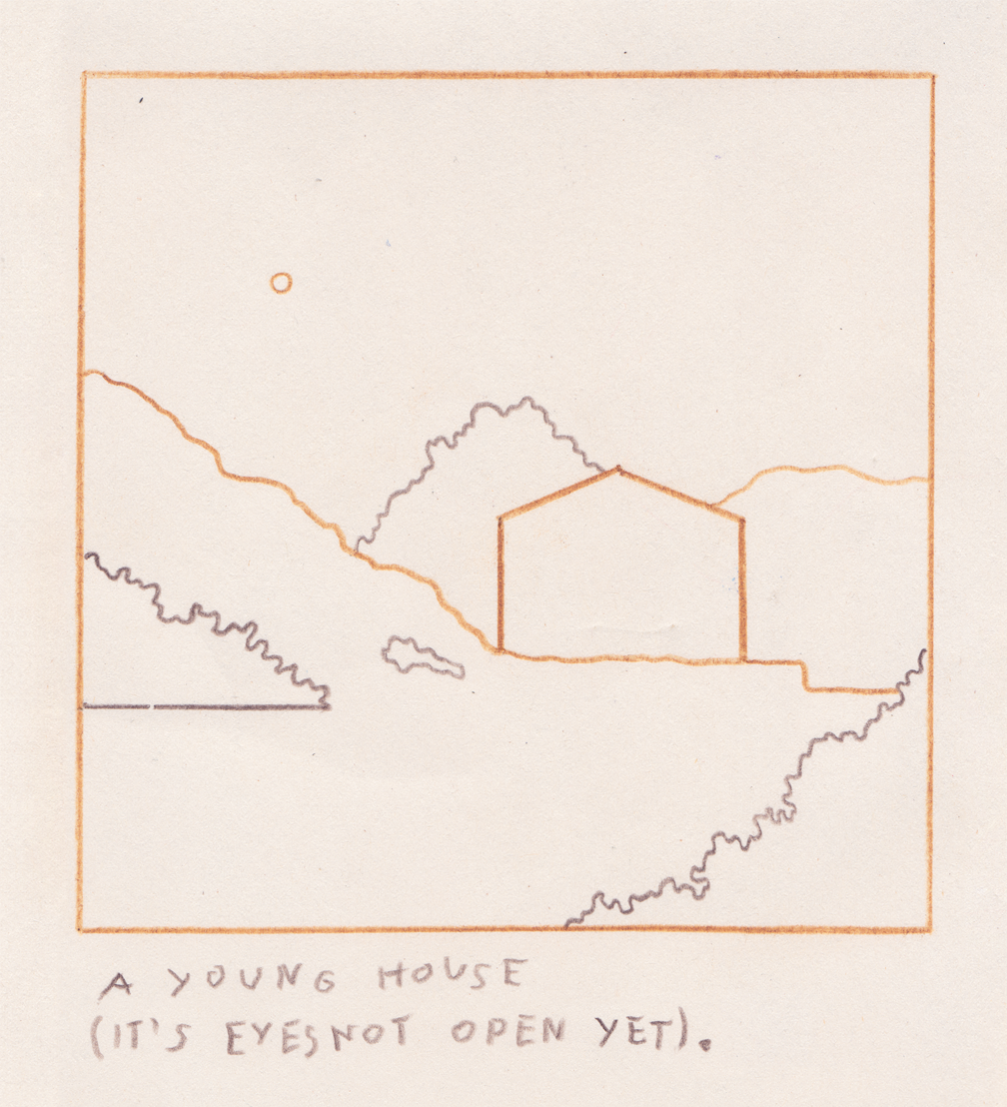

Sustainable architecture breaks from the paradigm of productive construction. We can talk about interaction with the environment and cultural context, socio-economic sustainability, and inclusion. In the context of our artistic interventions, we often think about time and space: when is it better not to intervene or not to build at all?

This June, we spent a month in an art residency in Vilnius, exploring the case of the Lithuanian National Stadium — a project that has been started and cancelled several times, with its foundations built and demolished more than once. Today, it is a vast inactive construction site in one of Vilnius’s residential districts. Surviving multiple systemic and economic changes, the stadium has become something of an urban legend, revealing the dramaturgy and tensions of urban processes — both personal and collective. What happens when a vision becomes reality? Looking at the ambitions and promises behind architectural projects, as well as their ghostly presence in the city, we thought about what it means to live amid unfinished visions, and imagined ways of inhabiting them.

During the residency, in collaboration with the Architecture Fund Lithuania and French artists Lucille Leger and Jacques-Marie Ligot, we created an archive of the stadium’s waiting spaces. When a project has been stalled for forty years, it becomes a kind of hourglass. How do you archive time when it’s no longer counted? What light-touch acts of resistance can oppose the prevailing logic?

What, in your opinion, is a safe space?

Gaiss:

A space where a person knows where they are entering, and understands where they can leave. They can see daylight and the outdoors, and can orient themselves indoors. In our projects, we plan windows carefully — through-views are important, as are intermediate views that help one understand their position in the building in relation to the outdoors. One example is our House with Four Roofs. This linear building stretches across the plot, with multiple intermediate views that extend the interior space and reveal its relationship to the garden.

Gel.office:

A space that is transparent, accessible, sufficient, planned, welcoming, and inclusive. Equipped with doors that can be closed and opened when needed, and with at least one window for fresh air. A place where you can think, speak, and plan ahead. With a healthy microclimate, without mould. A space you can rely on.

Can an architect improve the order of the world?

Gaiss:

The order of the world is created collectively, not by an individual or a representative of a single profession. Architects must work with collective interests and needs, with the planet’s resources, and with human well-being — and do so responsibly and optimistically. That’s when there is a chance to improve our surroundings.

Gel.office:

Anyone can create positive change in their immediate microcosm. In our practice, we don’t offer technical solutions, but instead aim to expand the space for reflection, where things can be questioned and contemplated freely. One of the focal points we’ve worked on recently is the Rail Baltica project here in the Baltics. In 2024, we organised the artistic research project Baltic Lines, involving 14 artists from the Baltic and Nordic countries, which culminated in an exhibition in Vilnius. Our curatorial focus in Baltic Lines was not technical in nature — we didn’t ask whether the train was necessary or when it would depart. Instead, we sought to think critically about the direction of its integration, asking: where is it going?

Maike:

Historically, architecture is full of utopian projects — mostly by singular male architects — reflecting a belief that architects have the power to fundamentally change the world through design. On the one hand, this idea feels like it promotes a kind of god complex, but on the other, architecture deeply shapes our lives and can have long-lasting environmental, social and political impacts, so architects should be aware of this responsibility.

What working methods or strategies do you use when getting to know a space or environment where you will be creating?

Gel.office:

We always start by asking — is intervention justified, and if so, what kind of materiality can represent it? Because we describe our work as context-sensitive, we begin by looking for historical and contemporary traces in archives, books, and online, to build a broad understanding of the situation. We try to find oral testimonies and urban legends, myths, and stories. We reflect a lot on our position, on what we can speak about from our own perspective.

Maike:

My working methods shift depending on the project, but I often begin by getting to know the space and its context by writing and listening. I do this through site visits, conversations with people who live, work, or use the space. Writing helps me process initial impressions, emotions, memories, and questions that this may evoke. I try to reflect on my position, what it means for me to be there. This approach combines intuitive and personal responses with collaborative and research-based strategies.

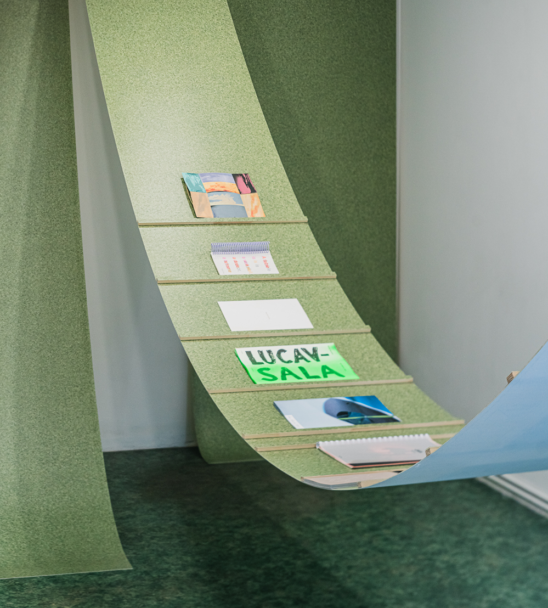

For example, in Hosting Space, a project I led at Hordaland Kunstsenter in 2023, I was commissioned to transform the entrance, reception, café, and bookshop. The aim was to create a space that reflected the centre’s focus on mediation and considered how visitors are welcomed and engaged. Instead of separating design from the art centre’s programming, I proposed merging the two: the design process unfolded as an exhibition and public programme addressing topics like accessibility, support, and gathering in art institutions. Materials from the exhibition and events were later integrated into the renovation project.

For example, in Hosting Space, a curatorial and design project I led at Hordaland Kunstsenter in 2023, I was invited to redesign the entry, reception, café, and bookstore of the art centre. The brief was to create a space that reflected the art centre’s focus on mediation, and to challenge ways of welcoming and engaging with visitors to the art centre. Instead of separating design from the programme, I proposed combining the two: the design process unfolded as an exhibition and public programme exploring access, support, and gathering in art institutions. Materials used in the exhibition and events were later used in the renovation.

The programme involved artists, architects, researchers, and care workers, who hosted workshops, screenings, and talks. This holistic approach made visible the many dimensions that shape that shape how people experience space — not just the physical elements, but also atmosphere, communication, and community.

Pauls:

I haven’t arrived at a specific algorithm for starting projects. Overall, I enjoy that working with space and context forces me to keep an open mind and accept that I will learn a lot from the place itself during the process. Lately, I’ve been drawing on the work of conceptual and performance artists from the 1970s to the 1990s, like Rirkrit Tiravanija and Bonnie Ora Sherk, who focus on the body and its actions in space rather than on the space itself or the objects within it. This helps strip away the unnecessary. Sometimes, all you need for a sports hall is an unused field and some sport to be played.

Viedokļi