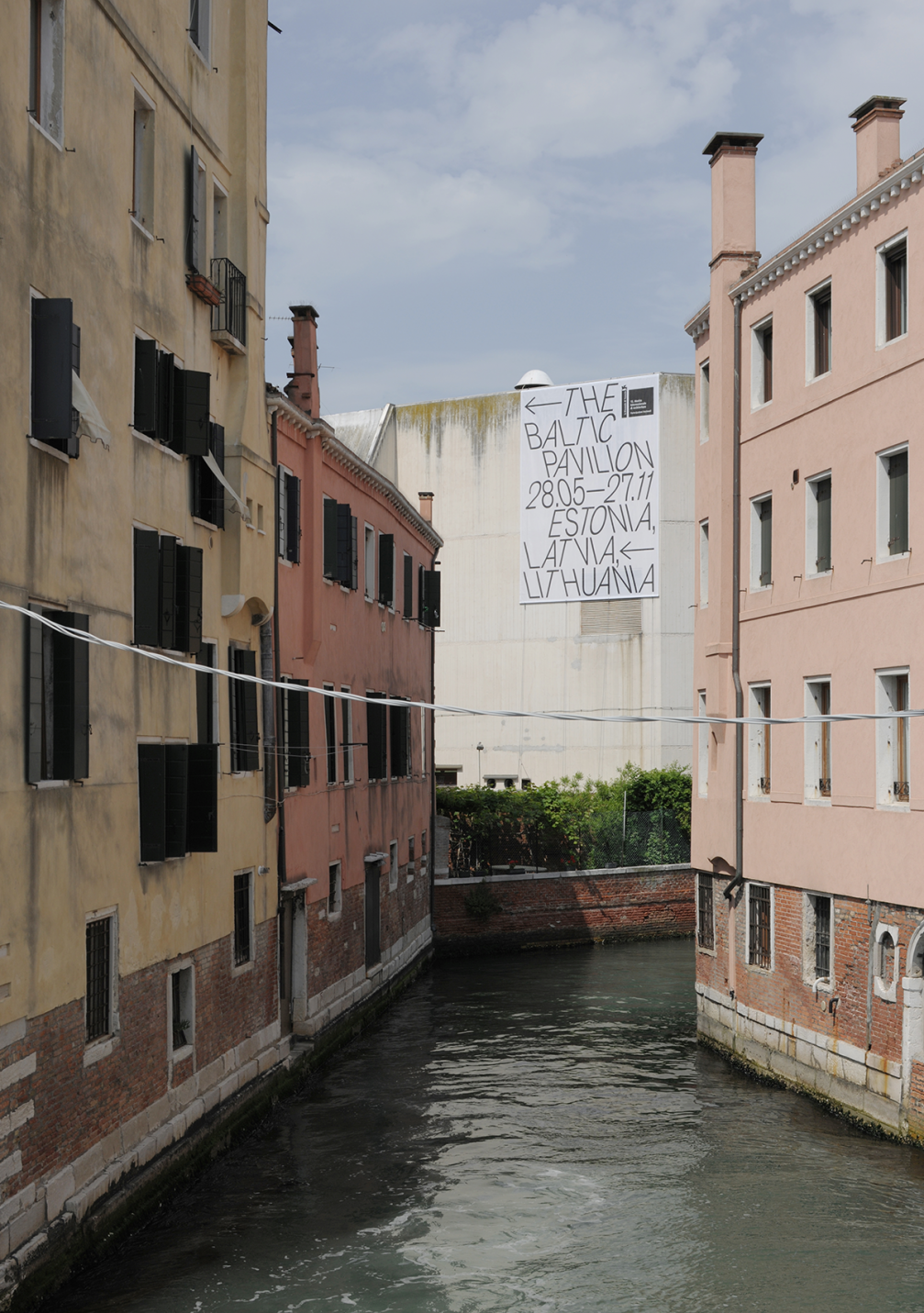

In the two weeks since the first united pavilion of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia opened at the Venice architecture biennale, it has been widely published in the international architecture media. It stands out among the rest with its scale, ambition and focus on subterranean and infrastructural spaces. By involving a broad circle of authors in the making of the exhibition, the curators have managed to build an impressive collection of curious objects and ideas from the Baltics.

Visiting The Baltic Pavilion is like finding yourself inside a life–sized Pinterest board — there are visually attractive objects scattered all around, potentially tagged with #Baltics, #resources and #infrastructure. Individually and as a collection the items are curious and inspiring — where else could one find a map of blooming plankton next to a Rail Baltica–themed set of playing cards? There are over 100 objects on display, featuring samples of rocks, a piece of an underwater power cable, photographs of industrial landscapes, a pile of firewood, a collection of ceramic sculptures, videos of microrayons and kolkhozes. The peculiar selection gradually uncovers a story of three small countries transitioning from the Soviet Union to the European Union — their inventory of the existing underground resources and infrastructural networks, attempts to stabilise the inherited economy and yet unachieved but promising future prospects. All that plays out underneath a white fabric sky that softens the robust geometry of Palasport Arsenale.

The Baltic Pavilion is a physically challenging exhibition — in order to see the objects the visitor must climb up and down the gymnastics hall tribunes, at times sticking their head above the white canopy, disappearing into spatial pockets or balancing on the edge of a step next to a large photograph. As a renaissance cabinet of curiosities it overwhelms with its diversity and richness, but does not offer a predefined route thematically, chronologically or geographically. This can make the visitor feel either liberated or annoyed — depending on the number of pavilions they have already visited that day. To get to know The Baltic Pavilion thoroughly and in an unhurried pace, you’ll need approximately 2 hours. To understand the meanings of the exhibited objects and to begin seeing links amongst them, you should be interested in and already know a thing or two about the Baltics.

After visiting The Baltic Pavilion I can’t help but wonder — would I be able to see the complete picture if I wasn’t from the Baltics myself? Would I have the patience to read all the descriptions of objects if I didn’t know the curators and feel obliged to show respect to their work? Is it enough to look at the work of geologists, engineers and spatial planners from a purely aesthetic perspective? I wish the curators had guided me just one step beyond — over the bridge that connects looking at things to thinking about things.

The relevance of cabinets of curiosities varies — some merely represent the adventurous life and broad interests of their owners while others have served for research purposes or been transformed into museums. I hope that The Baltic Pavilion will have an afterlife too — the relationships between the exhibited objects deserve to be studied further.

Viedokļi