Reinis Suhanovs received the Scenographer of the Year award at last season’s «Spēlmaņu nakts» («Players’ Night»), recognising his stage design for the plays «Persiešu valodas stundas» («Persian Language Lessons», performed at the Žanis Lipke Memorial) and «Arī vaļiem ir bail» («Whales Get Scared Too», at the Latvian National Theatre). At the Latvian National Theatre, an architectural object sits on the stage; and in the Žanis Lipke Memorial, the architecture — not originally designed for theatre — is made to accommodate a stage.

«Anton Chekhov once said there was nothing more terrible than sitting down in front of a blank page. This is also true for an empty stage room,» says Suhanovs on doing creative work in the «black box» of contemporary scenography. «Playing outside of a typical theatre environment is not only very interesting; it is often also easier than playing in a theatre. In an environment with context, with matter that has already been worked on and lived in, the task of the scenographer is to find a sensitive, witty and artistic way to add to it.»

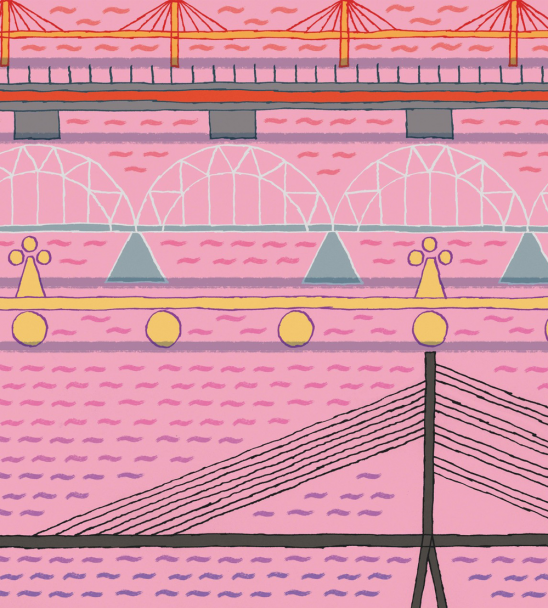

Latvian theatre is increasingly finding its way into unconventional spaces — the International Festival of Contemporary Theatre «Homo Novus» stages plays both in Riga’s theatres, as well as in museums, outdoor spaces, industrial spaces, abandoned buildings and elsewhere. One of the basic aims of the annual Valmiera Summer Theatre Festival, led and curated by Reinis Suhanovs, is to introduce festival–goers and local residents to an often–unseen side of Valmiera’s urban environment; to this end, the festival includes plays staged in industrial areas, the forest, an ancient stockyard, a swimming pool, a bus and other unconventional spaces. The theatre troupe «Kvadrifrons» has been active in the Riga Circus since 2018, making original and experimental use of the historically rich spaces at the circus. Suhanovs is quick to note, however, that the 1990s phenomenon of staging plays in unconventional spaces is more an act of remembering than of new discovery: «Wherever you can look, that’s where the stage is.»

These unconventional environments are particularly well suited the festival format — adapting premises for visiting plays has the benefits of low rent, a large staging area and an environment rich in imagery. «Much can be learned from an existing context; this reality allows as to absorb the valuable,» Suhanovs says. «At the same time, a powerful environment — which, in the case of Latvia, includes all of the small theatre stages — has limitations that eventually lead to repetition. This is why everything must begin in the «black box», where, each time, we create detailed rules for the game and a new spatial world.»

Persian Language Lessons

Russian playwright and director Gennady Ostrovksy’s play «Persiešu valodas stundas» («Persian Language Lessons») premiered in November 2017 at the Žanis Lipke Memorial designed by Zaiga Gaile. The play is based on an imagined episode from Polish Jewish writer Bruno Schulz’s life in a concentration camp during World War II. Reinis Suhanovs’ role as a scenographer for the play is no coincidence — he is the designer for the layout of the museum’s permanent exhibition. Music for the play was composed by Jēkabs Nīmanis, author of the memorial’s audial presentation.

It is hard to imagine an environmental context more appropriate for Ostrovsky’s play than the museum; still, staging a play in a space not designed for theatre imposes certain practical limitations and narrows the form in which scenography can be realised. The memorial’s premises are ill–suited to both contemporary «black box» scenography and the traditional coulisse scenography approach. «There is a third way that I call installation-type scenography, where space is defined not by the interior of a «black box» or through coulisse manipulations, but rather by an object. An added benefit is that you can easily bring the installation, stage a play, then take it and leave,» says Suhanovs.

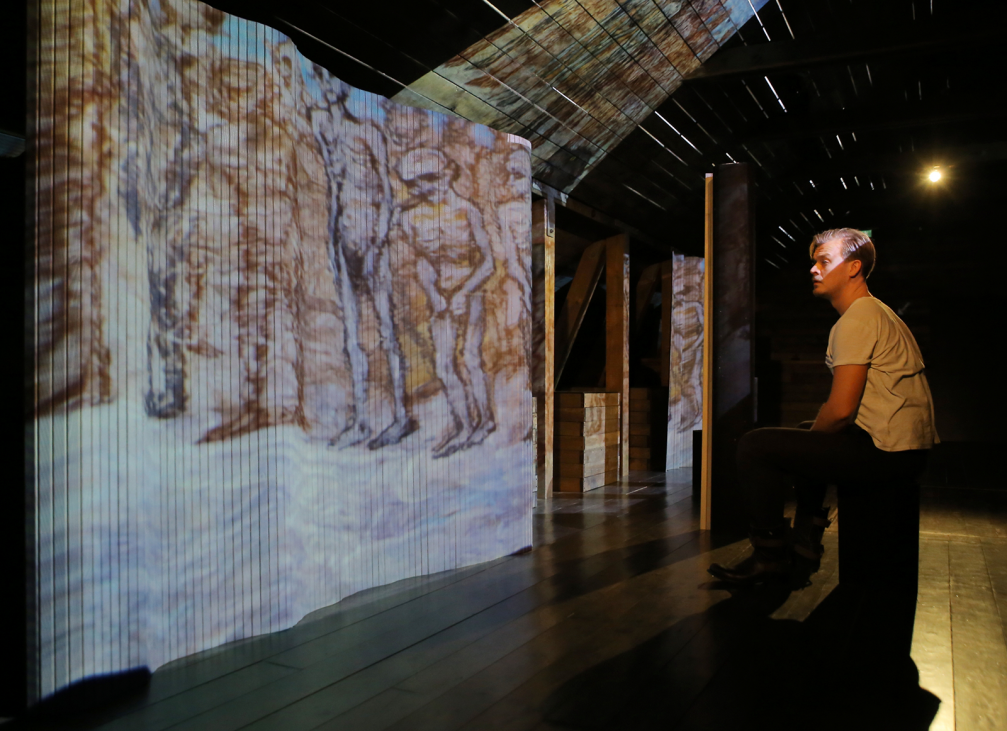

The idea of a mobile, adaptable space echoes the environmental context: a sukka — a fragile wooden structure with transparent paper walls painted by Kristaps Ģelzis — sits on the ground floor of the Lipke Memorial, right above the basement bunker. It is a temporary shelter — a direct reference to the biblical story of the mobile home with views of the Promised Land, gifted by God to Moses on his way through the desert. «The sukka is a temporary home, and this play the same — it’s temporary theatre that we can pick up and bring along,» Suhanovs explains.

The collection at the memorial also includes a Torah — a scroll of Jewish sacred writings — re–imagined through the scenography as a spatial conceptual object consisting of board panels of various sizes that can be rolled up like scrolls. «Torahs, or rugs, are a central semiotic element of the play; at the same time, they are highly functional as they complement the actor. As an artist, I’ve created a modular structure that the director can rearrange freely. The scenography is live; it responds to the actor in real time,» explains Suhanovs. During the play, the scrolls serve not only as books and rugs; they also morph into stools, an oven, the chimney of a gas chamber, a children’s bedroom, a hideout. The curved shape of the panels lets them stand upright, forming a vertical wall that serves as a projection screen for videos created by costume designer and animation artist Velta Emīlija Platupe. Suhanovs stresses the importance of the videos in the play: «Velta processes themes of the Holocaust and its tragic history in the abstract. Directly depicting the things happening in a gas chamber or designing the stage as the interior of a death camp would be too much. All of that is already in the text. A panel that rolls up into a gas chamber chimney is a less obtrusive solution. There is no need to physiologically burden the viewer with additional emotion. Should someone wish to emotionally connect to the content, they will, but the aesthetic of a play should not be intrusive or bothersome. This is how I search for my scenographic language — the viewer should be able to connect to the next layer of depth of their own accord, but the external form has to remain complete, as a neutral background. The more you read it, the deeper you can go.»

Whales Get Scared Too

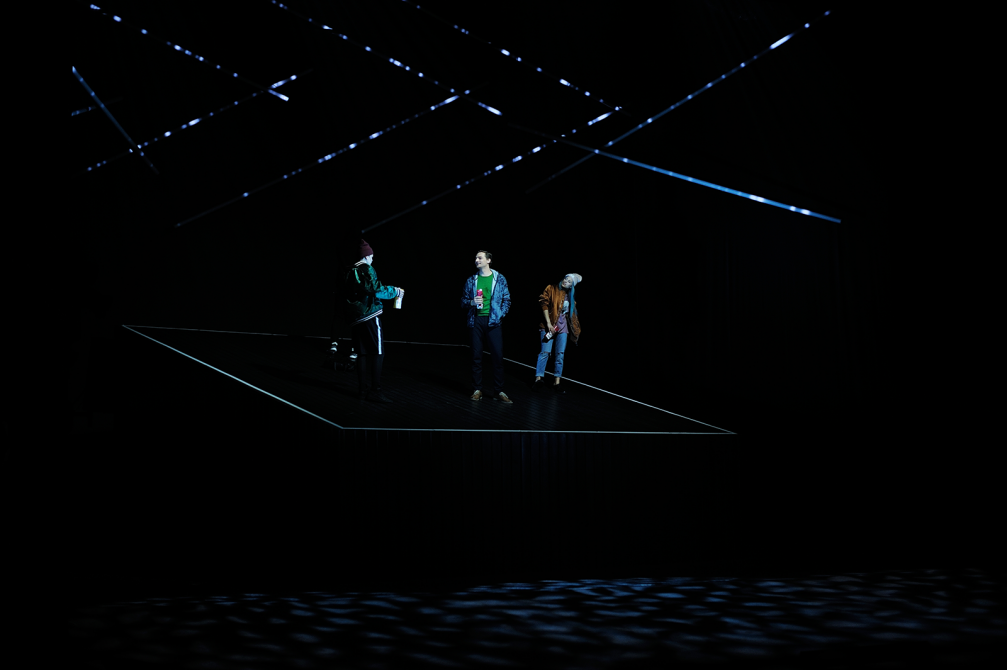

The Latvian National Theatre play «Arī vaļiem ir bail» («Whales Get Scared Too»), directed by Elmārs Seņkovs, received 9 nominations and 4 yearly awards last season — to Igors Šelegovskis as the New Stage Artist of the Year, Artūrs Dīcis for his original script, Oskars Pauliņš for his stage lighting and Reinis Suhanovs for his scenography — as well as the viewer’s choice award. The play tells the contemporary tragicomic tale of average Latvian Jānis Bērziņš’ struggle with mid–life crisis, depicted on-stage as a series of short, dynamic scenes. Suhanovs notes that Dīcis’ writing resembles a film script more than it does a theatre play: «The rhythm of the scenes could have easily resulted in a compartmentalised sort of «door comedy» stage design with action moving from room to room. But the conceptual starting point for the play was found precisely in thinking about the basic differences between cinema and theatre.»

Visually, the stage design consists of an archetypical black wooden building that, through constant revolution and with the aid of a couple of props, conjures the theatrical space. Continuous movement is the main element of the stage aesthetic, supporting the flow of the play. «The subjective point of the cinema audience is in constant movement in relation to space, while in theatre, the scenographic world is frozen in time. In this play, I offer as the static point of reference this spatial object — the house —, in relation to which the audience finds itself in constant movement, travelling around it along with the entire theatre. Like in real life, the continuous movement provides changing visual and architectural information,» Suhanovs explains. The turning of the stage revolve also influences the technique and style of acting — instead of ending, scenes are turned away from the stage, or, more accurately, the stage turns away from the scenes, leaving the actors off–stage. Suhanovs stresses the significance of stage lighting in the overall stage design composition: the light, too, is ever–changing, just like in nature. The dramatic culmination of the play takes place as a window is punched into the architectural form, piercing the facade both literally and metaphorically and connecting the inner world of the characters to the outer shell.

In response to his «Players’ Night» award, Reinis Suhanovs notes that conceptual artistic explorations with special importance for the author like his stage designs for both plays are rarely understood and recognised by the public: «This is, of course, a pleasant pat on the shoulder and a surprise. But where I as a scenographer get the idea for a space and what the audience eventually sees are two completely different things. In reality, there is no need for the audience to know this, since visual imagery influences the subconscious.»

The play «Whales Get Scared Too» can still be viewed at the Latvian National Theatre; tickets are available on the theatre’s website.

Viedokļi