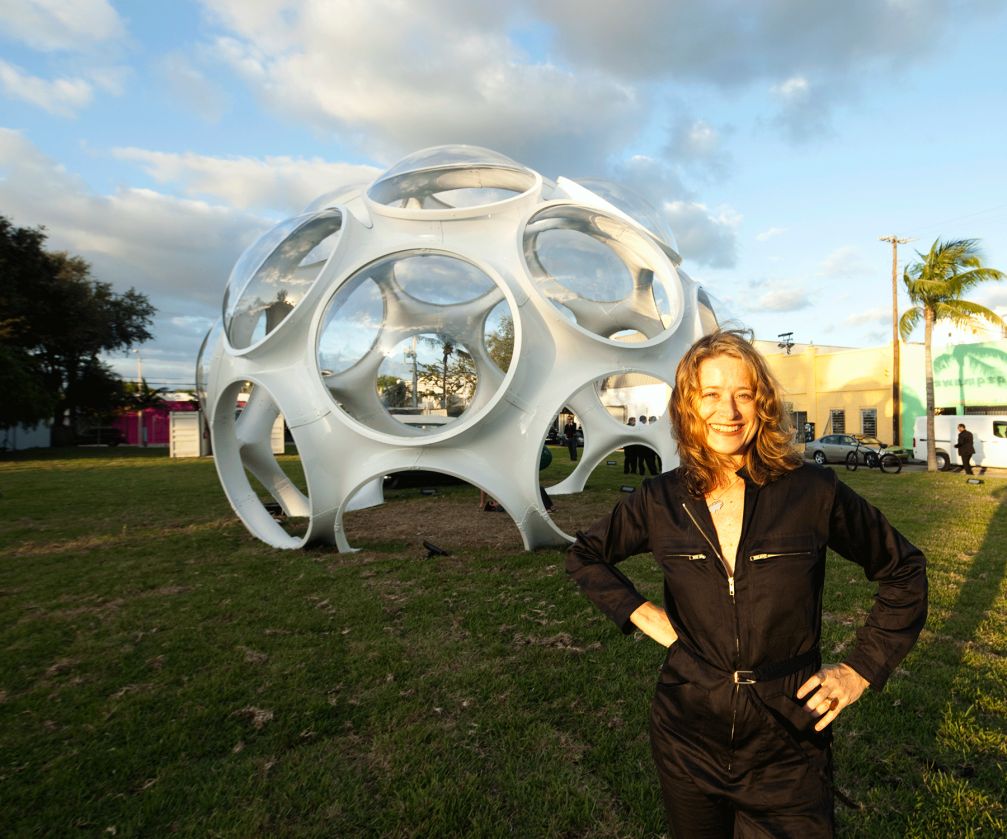

I had the chance to meet and interview Elizabeth Thompson, Executive Director of Buckminster Fuller Institute in November 2013. The Institute, based in New York, is focused on preserving, studying and extending the heritage of R. Buckminster Fuller (1895 – 1983) — probably the most influential design thinker, inventor and educator of the 20th century.

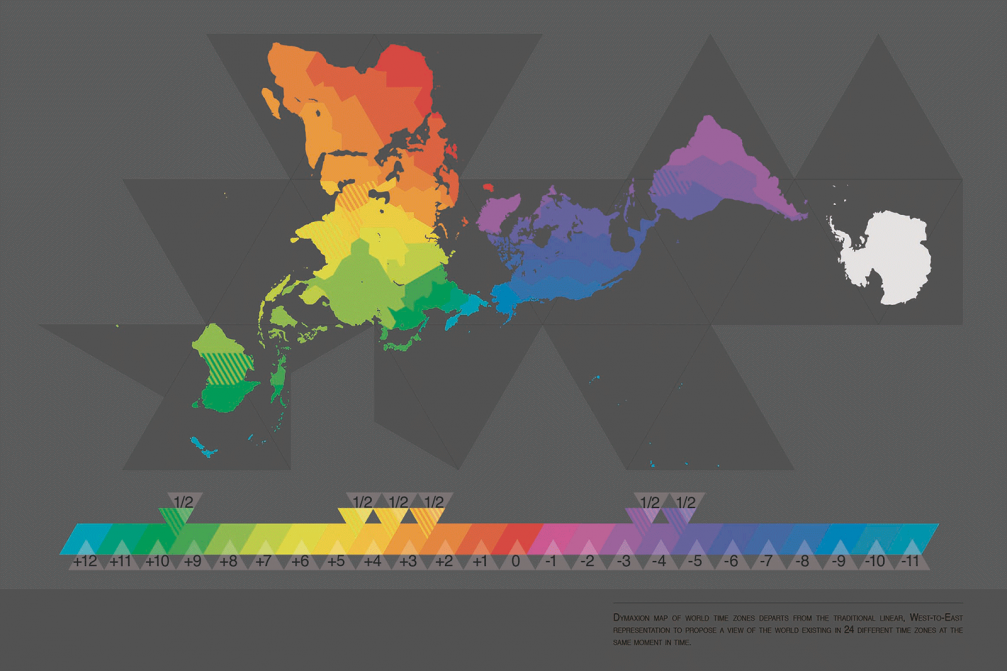

My contact with BFI started in spring 2013, when I responded to the Institute’s open call to submit proposals to re–interpret Buckminster Fuller’s iconic Dymaxion World Map which he conceived in 1938 and first published in Time Magazine in 1943. As it were, Oskars Weilands and I responded to the call and submitted an entry called Timezones, which was selected by BFI’s jury as one among 11 finalists, out of more than 300 entries. This made me curious to learn more about the Institute’s work and to establish closer communication; therefore, last autumn I visited them in New York with the support of US Embassy in Latvia.

What is BFI’s mission?

BFI’s mission is to promote the design principles underlying the profoundly relevant legacy of the 20th century visionary R. Buckminster Fuller. The principles stem from Fuller’s deep study of how nature works… and by extension the understanding of, as Fuller coined it, «the operating manual for Spaceship Earth». As an approach to addressing complex problems, they include comprehensive, anticipatory, ecologically attuned, scientifically verifiable, visionary thinking.

The principles encourage «starting with the Universe», in other words, seeing the bigger picture context of the problem–space and solution you are engaging, and «doing more with less» — accounting for each unit of energy required for the solution and maximising efficiencies.

What are you trying to achieve by running the Buckminster Fuller Challenge?

We are simultaneously seeking to encourage and support an emerging field of practice, which we identify as a «whole systems» design approach and celebrating exceptional examples of what Bucky called comprehensive anticipatory design science.

Are you achieving this? How can you know?

We know we are achieving this by the consistent increase in entries to the Challenge, the up–take of the whole systems comprehensive design language we use in our material by others, and the big impact that winning the Challenge has on our finalists.

[From BFI’s homepage: «Winning entries for the last six years have applied a rare combination of pragmatic, visionary, comprehensive and anticipatory thinking to tackling issues as broad as urban mobility, coastal restoration and innovation in biomaterials packaging. BFI has created an application process for entry to the Fuller Challenge in which global changemakers grapple deeply with a unique set of criteria. Internationally renowned jurors and reviewers look for whole systems strategies that integrate effectively with key social, environmental and economic factors impacting each design solution.»]

For instance, in 2013 the winner of the Buckminster Fuller Challenge was Ecovative: an innovative materials science company, which uses local agricultural waste to grow fungal mycelia that can be transformed into a number of eco–products, from packaging materials to building insulation and car bumpers. This is clearly an alternative to currently used non–degradable, environmentally harmful materials derived from petrochemicals.

What kind of a world are you trying to build by these and other activities?

Bucky called for identifying the «preferred state» as the first step of any design process — a rigorous exercise which challenges you to clearly imagine and articulate a future in which your solution has been fully and successfully implemented. He also challenged us all to «create a world that works for 100% of humanity, in the shortest possible time, through spontaneous cooperation without ecological offence or the disadvantage of anyone». This is the world we are building.

Is sustainability not already hijacked by corporations and used as a marketing tool? Or is it real?

The definition of sustainability has lost any rigor or standards for what it actually means. I think Bucky’s Challenge defines, from an operational vantage point, what en end–state of sustainability might require, at minimum.

[From BFI’s homepage: Entries must meet the following criteria:

- Visionary — put forth an original idea or synthesize existing ideas into a new strategy that creatively addresses a critical need;

- Comprehensive — apply a whole-systems approach to the design and implementation process and aim to address multiple goals, requirements and conditions in a holistic way;

- Anticipatory — factor in critical future trends and needs as well as the projected impacts of implementation in the short and long term;

- Ecologically Responsible — enhance the ability of natural systems to regenerate;

- Feasible — rely on current technology, existing resources and a solid team capable of implementing the project;

- Verifiable — able to demonstrate authentic claims backed by empirical data;

- Replicable — able to be adapted to similar conditions elsewhere.]

Is there something everyone could do about sustainability? Are designers somehow better equipped for the task?

Designers are fundamentally problem–solvers, and this is a highly useful skill set when it comes to achieving a sustainable future. Each of us has a role to play in meeting this goal. The opportunity is for each individual to bring what is unique to themselves to the task at hand and be rigorous in their self–assessment as to success.

Who is today’s Buckminster Fuller?

The globally distributed network of comprehensive design pioneers!

What are the opportunities and risks in crowd–sourcing design? Is this the future?

Ultimately major change has to work for people on the ground, in their lives. And someone has to be responsible and accountable. Certain types of design and visionary thinking lend themselves better to crowd–sourcing. Others do not.

What new opportunities does our always–connected, always–on age bring to design? How does it change design methods, processes, and, indeed, purpose?

It enables us to see the whole system in order to understand better the game rules at play in a way Bucky predicted but was not available to him while he was alive. The connectivity allows for «spontaneous cooperation and collaboration» to take place in real–time as we have seen in many world–changing political and social events these last few years.

Emils Rode would like to extend his heartfelt thanks to the US Embassy in Riga for their support that made this interview possible.

Viedokļi