Illustrator Sergiy Maidukov is one of the most accomplished graphic artists in Ukraine, combining expressive stylisation with scenic spatiality in his work. Sergiy started his career as a designer, but his pursuit of excellence led him to illustration, while his perseverance allowed him to collaborate with the world’s leading publications. Currently, the artist uses his talent to document what is happening on the front lines. He also immortalised the Ukrainian struggle for freedom on a collection coin of the Bank of Latvia.

Last year, you did a coin design for the Bank of Latvia. Can you tell us about the experience?

The first thing I want to do is thank all the people from Latvia for the incredible support for Ukraine! I appreciate it so much, I even have goosebumps while saying this. It really means a lot!

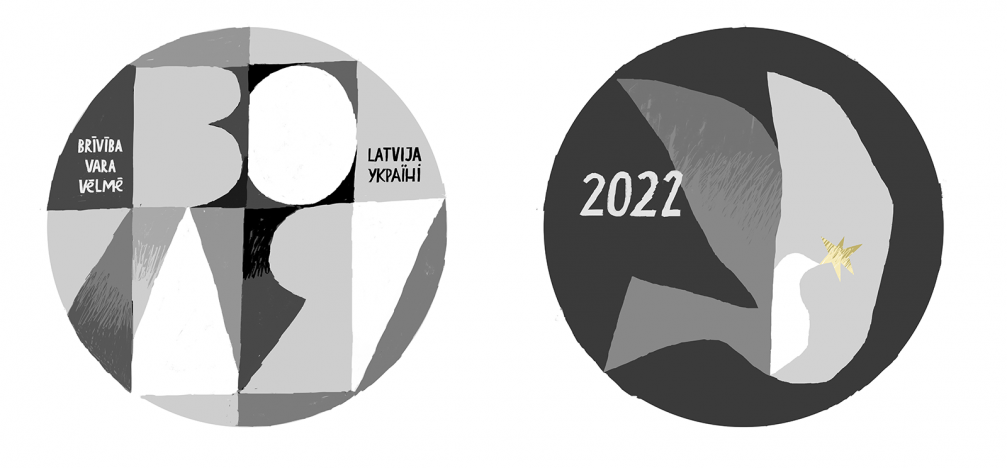

So, let’s get back to the coin. The Bank of Latvia invited me to participate in the design competition for Ukrainian artists. To my surprise, my work was chosen among the designs of other great artists whom I respect. For instance, Roman Minin is one of my favourite Ukrainian artists right now. I didn’t expect to win, I just thought that I was included for quantity.

Can you tell us a bit more about the concept behind the design and the meaning of the word «воля»?

When I got the invitation from the Bank of Latvia, I was very motivated by this word and it just stuck in my mind. All my ideas were either too conceptual or too simple, like Ukrainians raising their hands or a depiction of a sunflower, but images like that had already been seen again and again. So I asked myself, what is the most important thing for me right now? I realised, it is «воля». In Ukrainian, this word combines the meaning of strength, will, power, and freedom. It characterises so well what Ukrainians are doing. I had a word, so now I had to build something on top of that. I thought of Maidan, our Freedom Square, where the Ukrainian revolution took place. We cracked the stone pavement and used it to throw at the police. Fire and water cracked those stones as well. So I combined the stones of Maidan with «воля» for one side of the coin, and for the other I did a single piece of pavement.

After my concept was chosen as a winner, we explored some other ideas of mine. I had drawn this bird. I filled two sketchbooks with drawings of it while I perfected it. You can read the meaning of this bird in two ways — Ukraine is bringing a new start to Europe, a renewed understanding of freedom and dignity, and at the same time, Europe is giving a chance to Ukraine to join the European family. I loved this double meaning, and the Bank of Latvia loved it too so we chose this concept and combined it with «воля».

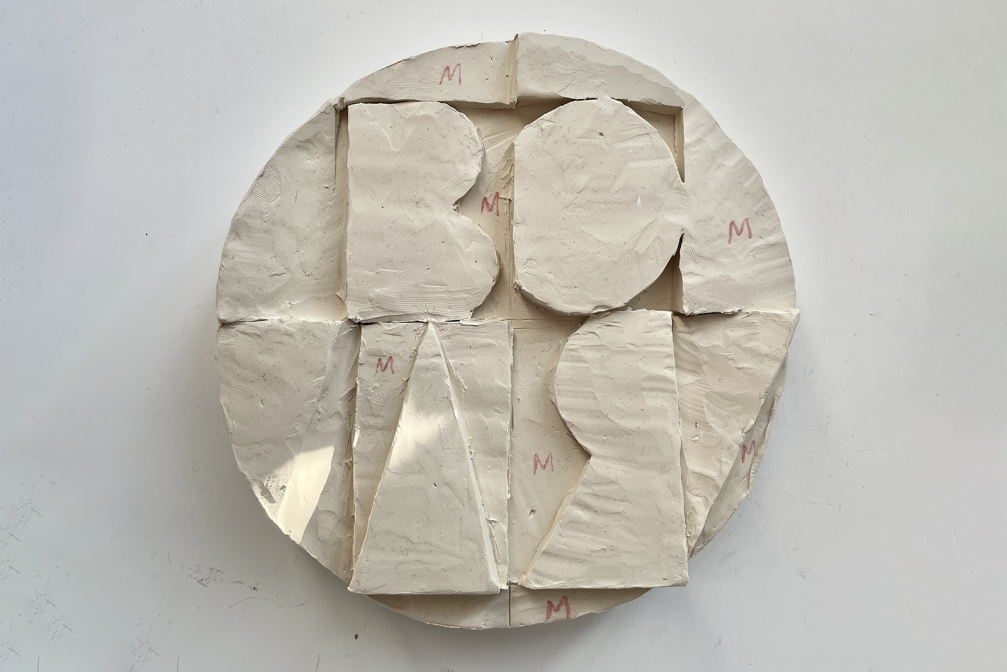

This has been the most unusual project for me in terms of media. I have grown as an artist because I needed to think three-dimensionally. I was lucky to get some sculptural plasticine and I got a burst of creativity working sculpturally. I plan to use the model to create some decorative plates and I will add some colour to them. It might be challenging though, because you need a lot of electricity for a kiln and it takes like twenty-four hours to burn the ceramics. With electricity going out, we risk cracking them.

You mentioned that you will make the decorative plates of your coin design colourful. You use a lot of bright and beautiful colours in your work. Does it come from Ukrainian culture and traditions?

Yes, you are right, it does come from Ukrainian art. Up until 2014, when the war started, I was keen to imitate Soviet aesthetics from the 1920s and 1930s. I was inspired by the artist Aleksandr Dejneka as well as some Latvian and Georgian artists, so I used a palette of limited colours. After 2014, I felt disgusted with Soviet art and I started my transition from what I loved to what I wanted to love. I came to use bright colours exactly because Ukrainian art has a very powerful palette.

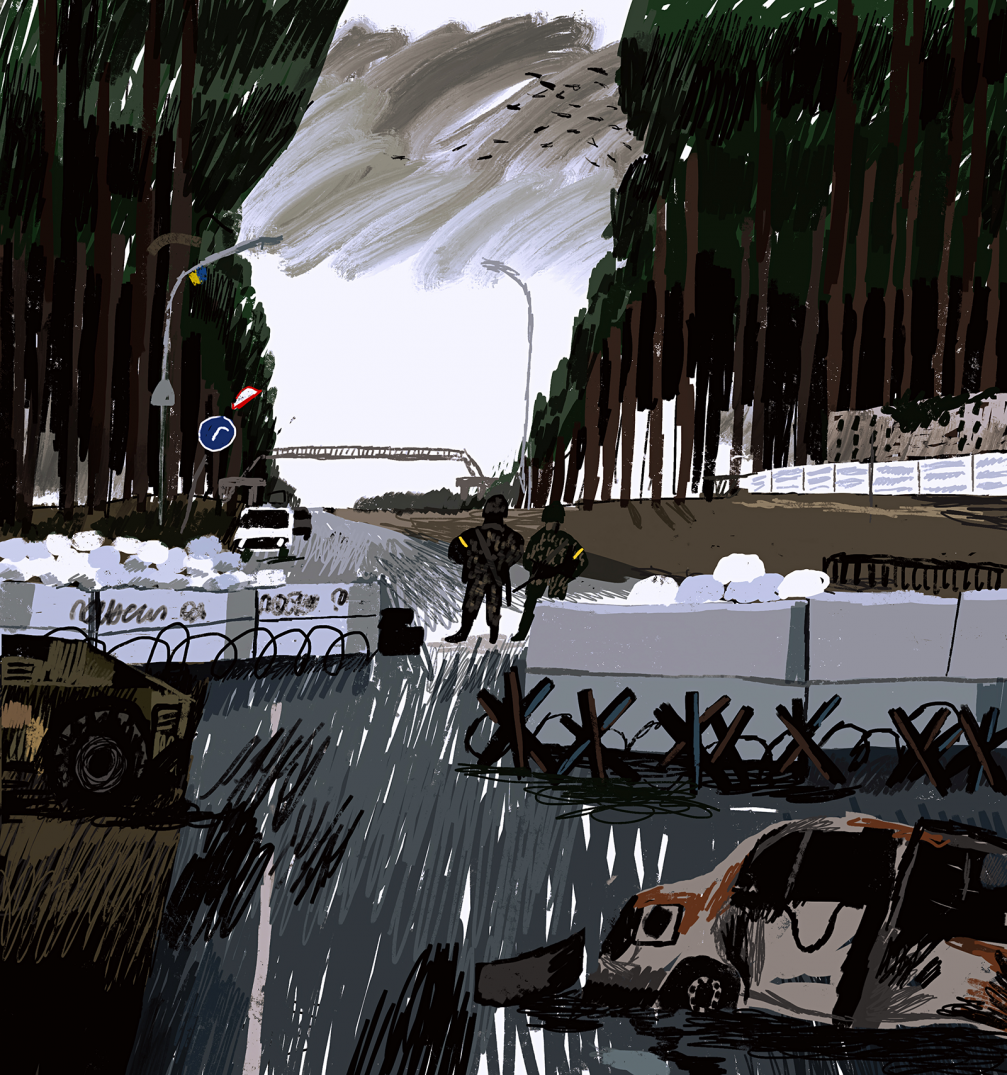

Has your illustration style changed again since this phase of the war started? It seems that your work is more urgent and emotional.

Yes, I do feel a transition of my style. On the one hand, I am happy with that. In art, change is very useful. You have to have different perspectives and explore new feelings and new levels of understanding, otherwise you just start to repeat yourself. On the other hand, I am not happy with this change. The sketchy lines and this emotional drawing style are mostly connected with the documenting I do. I love illustration because you can combine things and have a completely new message. When documenting something, you can still change the perspective and add some details that are not physically in your view, but you have less time to do the drawing. In some ways this documentary illustration style makes my metaphorical thinking weaker.

Do you feel like Ukrainian creatives find it important to document the war and use their creative skills to help Ukraine win this war?

It is important to tell the world what is happening, to reflect, to gain some money with your work and give it to the Ukrainian Armed Forces, to support Ukrainian people morally. Personally, I am motivated by two things. I had always been interested in war and I used to do some war archeology before the war started in 2014. We used to dig up helmets and guns from World War II. After 2014, my perception changed and I understood that my interest had been very superficial. If you are such a man and if you are so interested in adventures, go to the trenches! I think some part of me is still interested in war, so for me, going to the front line and documenting it feels like a necessity. At the same time, when I draw the things I see with my own eyes, I am compensating for my anger, sadness, anxiety, and fear.

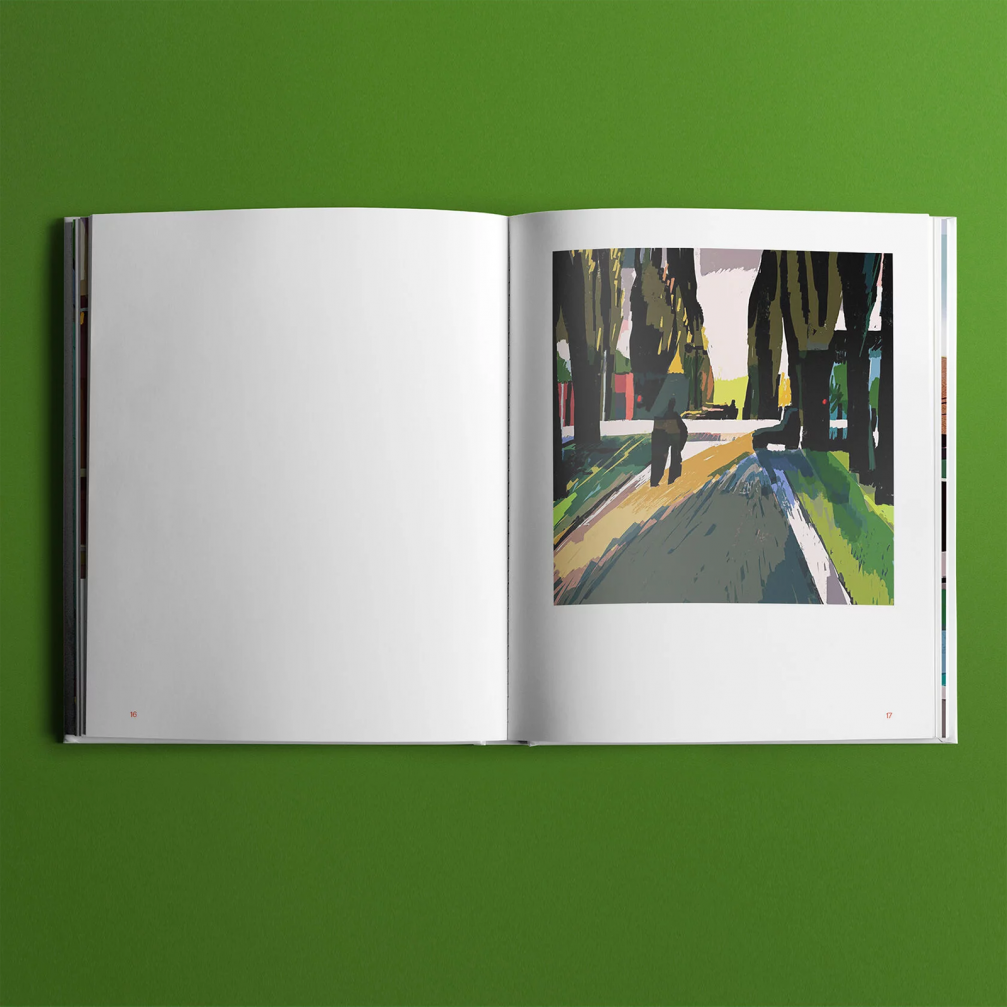

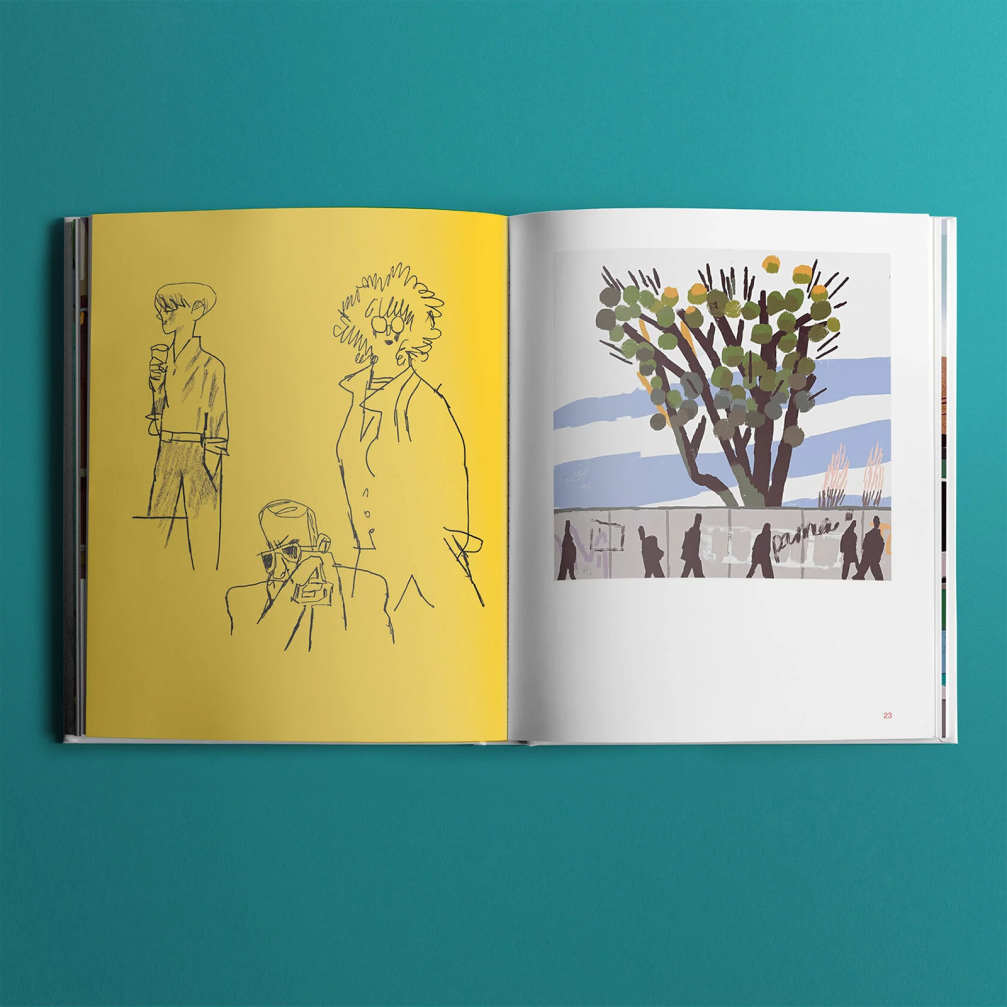

This is not the first time you’ve documented your surroundings. You also did a book about Kyiv in 2021.

The story behind the book is really simple. I wanted to do a graphic story and I saw many of my foreign colleagues using an iPad to do that. I got one myself and was very disappointed as I found working with characters and text bubbles on it very annoying. My new tool was just laying there for two or three months and then I finally decided that I should learn how to use it. I thought that it could work for drawing outdoors. Instead of bringing a box of paints, a palette, a beret and a scarf, I could just take my iPad. I started to draw things I see in the city and it helped me to develop my colour perception. I posted my drawings on social media and saw that people like them, so I decided to do a book. I was looking for a publishing house and IST Publishing, one of the best art publishers in Ukraine, was interested in doing this project.

We are planning for another book with my drawings of the war. I was hesitant at first, not wanting to commercialise my documentary work. As I said, it is my existential necessity to draw what is happening. But my friends and the publisher convinced me that this work is important. Despite the difficulties with electricity, security, and the economy, as well as the substantial deficit of paper, we hope to publish the book this year.

You used to work as a designer. How did you start your career as an illustrator?

I was working with brand identities, visual design, and print for a company in Donetsk. However, I felt that there is nowhere for me to grow, so I started to work as a freelancer for international companies. That gave me a chance to compare what design is like in the UK and what it is like in Donetsk, and I was not happy with the differences I saw, so I moved to Kyiv and started to work for an American company. But after a while, the company closed so I had to look for another job. I realised that I wasn’t a strong enough designer for the places I wanted to work at and the places that would hire me didn’t interest me. While I was looking for a job, I started drawing and posting pictures on my blog, and I also got some requests to do graphics for advertisements, thus doing something between illustration and design. In 2015, though, I stopped doing design altogether. I am a mediocre designer, but I don’t like to be somewhere in the middle of my community. I like to do something that is unparalleled.

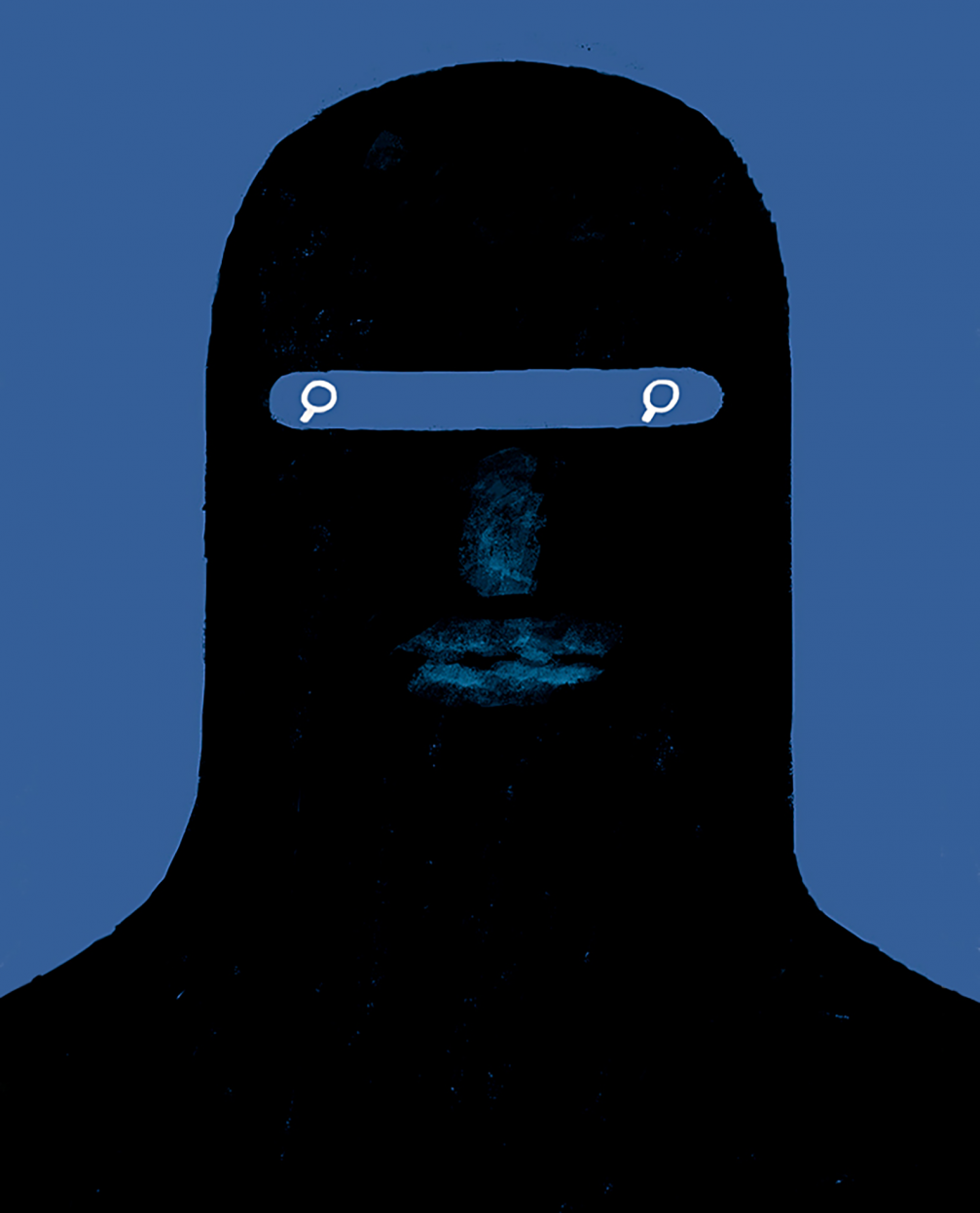

You’ve been very successful in illustration. You’ve worked with some of the most influential publications in the world, like The New York Times and The Guardian. How did you get to this international level?

For the first two years of my illustration career, I bombed editors with emails looking for work. I got some commissions from niche magazines like the Times Higher Education or a theatre magazine from the Netherlands. I was very happy, as nobody else was doing that — I was the first Ukrainian illustrator to work with foreign media. But still, my ambition was to work with the top media in the world, so I started the second round of email bombing. I got one commission in the first half year, then — two commissions in the next, then — three commissions, and four. Once you push through the threshold, you get noticed.

How is work now? I imagine that a lot of people see your illustrations now and the media all over the world want to get a Ukrainian perspective.

In the first five or six months of this phase of the war, world media showed an incredible interest in Ukrainian creatives, illustrators, photographers, columnists, and writers. My usual aim is to work for at least ten foreign media outlets a year. In 2022, I worked with twenty-one. I feel that this growth was fueled by war, and I am afraid that after the war ends, I will have to go back to my usual ten. Some of my colleagues who also work with foreign media have already experienced a drop in interest, but some of them have pushed through that threshold and they’ve got their ticket to work with the best art directors in the world.

Before the war, seeing a Ukrainian creative working on an international level was like seeing snow in the summer. Many editors and art directors thought that Ukraine was just some weird part of Russia or the USSR. Now, the world has noticed Ukrainian artists in music, in cinema, in illustration, in fashion, and in other fields. I hope that this interest will continue and will grow slowly and naturally. This was a revolution, now we need an evolution in the presence of world culture.

Can you name some of your Ukrainian colleagues in the creative industries whose work we should follow?

Oleksandr Grekhov, Maksym Palenko, and Anna Sarvira are my colleagues in illustration — they have a sense of humour and depth that I really respect.

I want to support the mother of my daughter, ceramist Tania Shku, at any opportunity. I love what she does. Other people who are dear to me also work in the creative sphere. Sofiia Horbachevska, a friend of mine, is a ceramic artist who is growing rapidly. Another friend, Daria Levchuk, creates fonts and graphic design. In architecture, I highly value my friend Slava Balbek’s studio Balbek Bureau. Currently, they are engaged in many social projects. Slava is a human engine. He has also founded the furniture brand Propro, which produces things of exceptional quality. I have used and tested them myself.

I have always wanted a carpet of the brand Gushka, and the softest blankets are produced by the Ukrainian brand Woolkrafts. They have great taste and quality. I have collaborated with this company myself.

Design brand Gunia Project offers ceramics, clothes, and accessories that translate traditional Ukrainian «visual melodies» to modern taste and market. In my opinion, the clothing brand Oliz follows a similar path — they have departed from traditional visual expression without losing their roots. The brand Lutiki offers elegant and affordable jewellery that feels contemporary, but refers to Ukrainian culture. I gave my daughter a Lutiki necklace, which resembles a pumpkin seed.

I would like to highlight the publishing house of contemporary art and culture, IST Publishing, with which I launched my book of Kyiv illustrations. In my opinion, they are the best in Ukraine. I should also mention the studio Grafprom, which helped with the design of my book. They have outstanding creative directors who have received many awards. Voluminous books on Ukrainian visual culture are published by Rodovid. Their approach is academic but not boring. The MOKSOP museum publishes books about one of the most important directions in Ukrainian photography — the Kharkiv School.

Last question. What will you do after Ukraine wins the war?

I would do two things. I come from Donetsk and there is a treasure of mine — our family photo albums with hundreds of photos, so the first thing I would do is to go to my parents flat and get the albums.

With the start of the war I decided to get rid of my prejudice for other people. You might base your perception of a person on one thing they did or said. I had a few of these misconceptions about others myself, but then I saw that one of them is now doing important things for Ukraine, the second one is on the front line, the third is helping children. Similarly, before the war, my perception of Crimea was that it was a beautiful place wasted — ugly architecture, bad service for a lot of money, garbage, and no evolution whatsoever for thirty years . So the second thing I want to do after the war ends, is to go to Crimea as a tourist and just be open, to engage with the problems instead of distancing myself from them.

You can follow Sergiy Maidukov’s work on his Instagram page.

Viedokļi