The village of Piedruja-Druja is located on the Latvian-Belarusian border, where the construction of an approximately 145 km long metal fence and other protective structures is currently being completed to limit illegal migration, which Latvia and other EU countries consider a hybrid attack by Belarus. The essay on Piedruja-Druja is part of a research project led by Belarusian designer Darya Ahrameika and Latvian researcher Danute Līva. During the walk, they focus on the village’s mixed cultural landscape, divided community, humanitarian crisis, and militarisation of the border zone.

Let’s start with the basics: I don’t know where you are or who you might be, but chances are, you won’t be able to visit Piedruja–Druja. The village is part of the Latvia-Belarus border strip. To enter its Latvian part, you must possess a special border pass issued by the Latvia State Border Guard. Generally, obtaining this permit is difficult — unless you’re white, European, and have a specific reason for your visit that isn’t tied to the ongoing humanitarian crisis.

The village holds a dual citizenship, with Piedruja in Latvia and Druja in Belarus. This duality has become its defining feature, as it’s often framed as the furthest corner of Latvia or the edge of the European Union. To make it spicier, the Daugava–Dzvina river flows through it, and the border runs straight down in the middle. Since the border is part of the Piedruja–Druja body, it’s deeply affected by the current politics, which, often negatively, affect the local community and refugees. It has become a sort of playground for state decisions. Even as I write this, I don’t know what it will look like in two years.

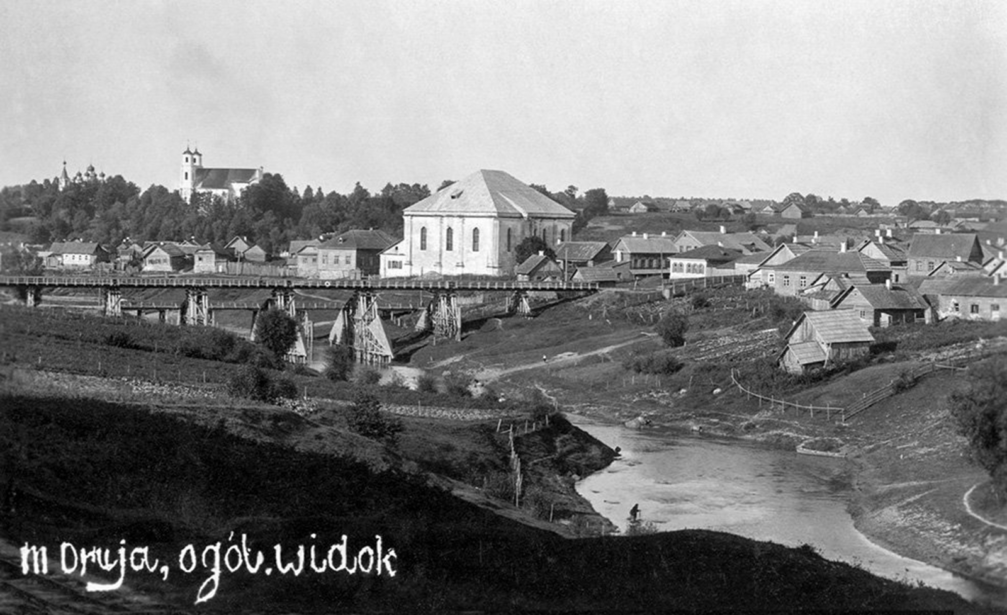

There was a time when this watery divide didn’t exist — during the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Russian Empire, and Soviet era, Piedruja–Druja was whole. People crossed the river freely, visited one another, moved to another riverbank, fell in love, and married across the banks. It’s almost absurd to imagine such closeness today. The divide gradually emerged after both countries gained independence and Latvia joined the EU, with the last straw being the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the humanitarian crisis. These events have led to the government’s decision to pursue the militarisation of the borderlands.

The humanitarian crisis — often referred to as a migrant crisis — was the main reason the border wall between Latvia and Belarus was completed so quickly. This migration route has been used since at least the 1990s but escalated in 2021. In response to EU sanctions, Lukashenko’s regime authorised 12 companies to issue Belarusian visas, particularly in Syria, Yemen, and Iraq, although the countries of origin have shifted since. Belarusian authorities are using refugees as weapons in their hybrid warfare, as the visas are accompanied by a false promise of «safe entry» into the EU.

The media in Latvia is using a dehumanising narrative around refugees, calling them illegal migrants and sometimes portraying them as terrorists. While in reality, they are people fleeing places affected by climate change, poverty, and war, including women and children. It’s unfortunate to see such responses from a country that itself has a fairly recent history of seeking refuge.

A year ago, I, an artistic researcher, and my friend Darya Akhrameika, a spatial designer, started visiting and researching Piedruja–Druja. Alas, this journey has been bumpy for us; to research Piedruja–Druja on-site is complicated. We visited Piedruja twice — first in 2024 and again in 2025 — and the accessibility of fieldwork is changing rapidly, even within the span of a year. This year, Darya was denied her border pass, as her Belarusian passport was used as a reason to claim that she poses a threat to national and state security. When visiting places by car, one might not be allowed to step out, even just to see a church, for example. These obstacles cultivate a lack of understanding of what is happening at the edge of the country and the violence against refugees taking place there.

Much of what I share here comes from our research and conversations with locals, including time spent with our collaborator Anna Griķe — an activist, anthropologist, and board member of the Latvia-based NGO I Want to Help Refugees. Recently, Anna published an article critiquing the absence of any mention of the humanitarian crisis at Latvia’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale, pointing out how architecture, particularly in this context, cannot be pulled away from politics.

So, for now, the least we can do is take a guided walk through Piedruja–Druja via this text.

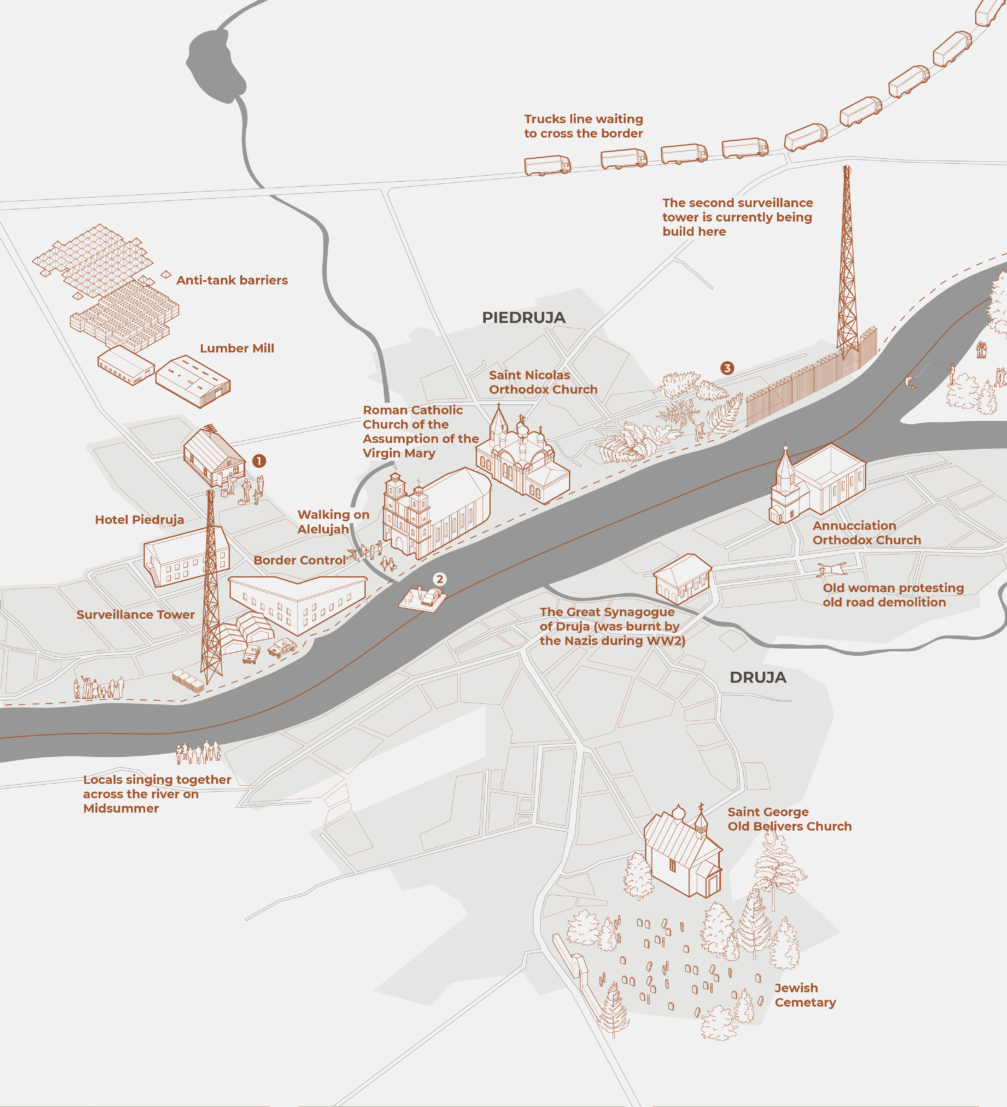

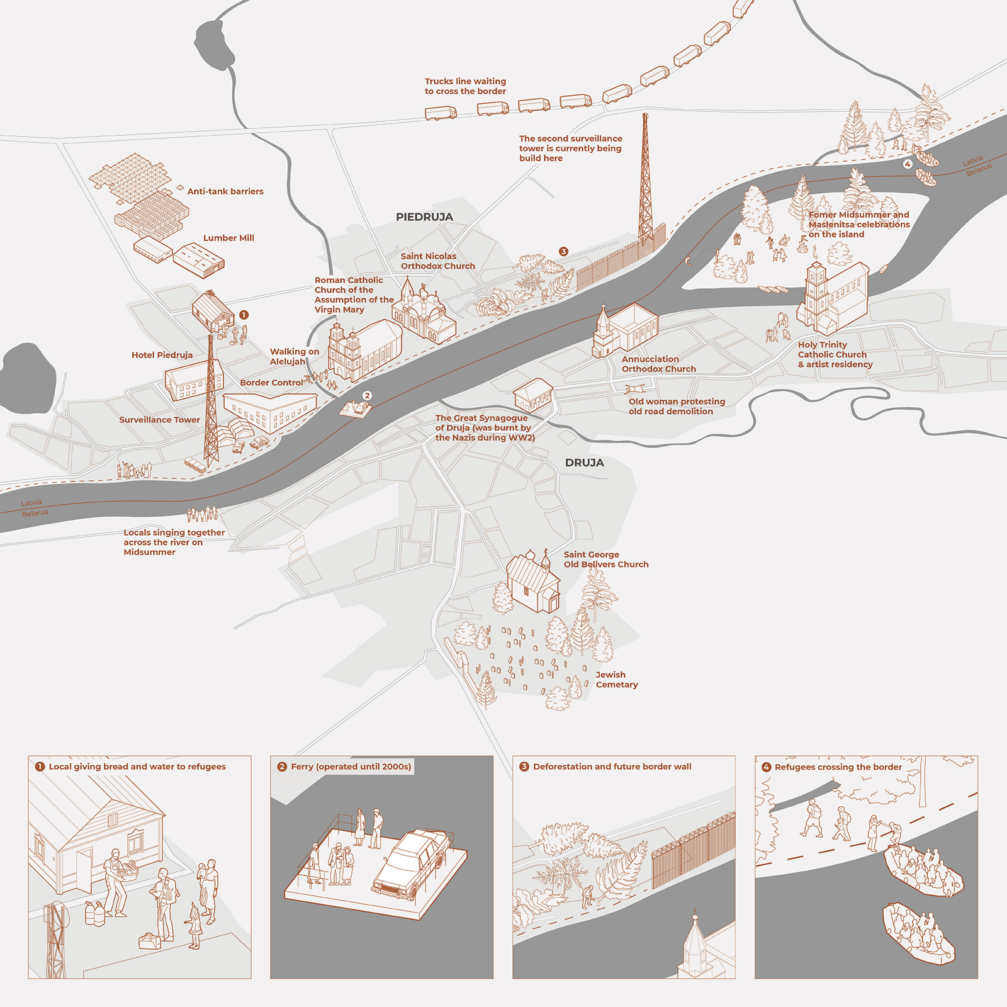

Let’s begin on the Latvian side! Instead of a grand Welcome to Piedruja! sign, you’re greeted by an abandoned Soviet lumber mill and freshly placed off-white anti-tank barriers — pyramids and modular concrete blocks stacked tightly together. They form a jagged, fortress-like meadow, hopefully awaiting for nothing to happen. Evidently, locals talk about it often, mostly criticising its cost and pointlessness. Many here live in poverty, without proper social support, making such militarised spending feel even more absurd in their eyes. One man said to us: «Do you really think, if Belarus arrives, this thorny meadow will stop them?» That question alone hints at the complex identities people who are used to shifting borders and changing anthems have here. Their sense of self isn’t bound to a single nation; instead, it’s a blended borderland, where several languages are spoken daily.

Going deeper and looking to the right, you’d see the only hotel over here, originally built as a two-storey Soviet apartment building. A business initiative by locals, who offered experiences like rafting from Belarus to Piedruja, fishing, and local cuisine. Now, barely anyone stays here, except for some relatives of locals and, last year, two Lithuanian construction workers, who were finishing the border wall. They were happy to be here because the pay was better than in Lithuania. They joked that Latvia must’ve liked how they built the wall back home, so they were invited to build one here as well. However, they were happy to go back home soon, as it was sad and challenging for them to witness families being pushed back through the border wall to Belarus.

The violence against refugees is an underreported and hidden issue. After Belarusian border guards leave the refugees at the border, they enter the brutal reality of pushbacks. From that moment on, they are unwelcome in either country and are constantly pushed back, only being admitted on «humanitarian grounds» if their life is in serious danger. Many experience numerous pushbacks until they run out of water and food. In 2024, there were 5,388 attempts to cross the border, and only 26 people were accepted on «humanitarian grounds». Sometimes people are pushed back to Belarus multiple times a day; therefore, several attempts could involve the same person. Often, border guards use electroshocks and noise and rubber charge grenades towards refugees. How did we reach a point where such violence is acceptable? Why can’t we recognise other human lives as equally valuable as ours?

I’ll be straightforward — like the hotel, much of the village is abandoned, empty, and ghost village-like. And this isn’t solely because of the rural decline; it’s due to the increasing militarisation and humanitarian crisis. This has fragmented the inhabitants’ lives and added more and more restrictions on what they are or aren’t allowed to do. Even mushroom picking and fishing require approval from the border guards. The guards have become the new nobility, deciding who may go where and who may visit whom. The restricted access deepens the isolation between Piedruja–Druja and the rest of the country, making people feel excluded and forgotten.

Continuing the route, we pass a vernacular home. One of its inhabitants recently passed away. This was the only person Darya and Danute met who had helped the refugees by giving them food and water and pointing them away from border control. The current, abusive system towards the refugees includes the prohibition of giving aid, and locals are expected to report anyone that seems like they could be from a so-called «third world country».

The same person who recently passed away, was someone Darya and I met while he was collecting snails in a plastic bag right next to the border control. Throughout the village, you’ll notice green posters announcing that someone is buying snails (with a required diameter of at least 2.8 cm), which will eventually end up on plates in fancy restaurants somewhere in Western Europe. He used to joke that during the Soviet times, he didn’t have to do such nonsense, because the employment salary was enough to cover the costs, unlike his current pension of 150 Euros.

Usually the biggest or the «main» building in the landscape of every small latvian town is the Palace of Culture; here that role is filled by the border control. It’s part of Latvia’s efforts to strengthen its eastern border, in order to join the EU in 2004. From a bird’s eye it is supposed to resemble a seagull, who is protecting Latvia. On the ground, it looks like any other mediocre early-2000s building. But this one is surrounded by a surveillance tower, military tents, Hesco bastion and quad bikes.

Moving deeper into Piedruja, yellow warning tape is wrapped around trees, screaming: «Borderland. Forbidden to stay without a passport and permit.» Another reminder of how politicised Piedruja has become, where local needs are secondary to national security. It’s a tough question, and there’s no single correct answer, since Latvia is protecting itself from its aggressive neighbours — but often this defence is mixed together with the refugees, who are also framed as a threat. A threat to what exactly? These are people in need of a home, weaponised by Lukashenko’s regime because of their vulnerable situation. These two narratives — the defence of Latvia and the plight of refugees — should be disentangled, and migrants recognised as human beings in need of international protection by the EU. What’s happening here mirrors Europe’s other borders (e.g., the use of pushbacks, surveillance, exclusion) — and it’s nothing to be proud of.

While the border control symbolises both protection and division, it stands on a site that once represented quite the opposite — a ferry. Every day, it carried people across the river in just a few minutes: horses, cars, children on their way to school, and people heading to church, the cemetery, shops — or simply going to party, or visit family and friends. After the Soviet collapse, it was sometimes called the international ferry. It stopped running in the early 2000s. For years, it remained here, lying in the grass and slowly rotting away — a painful reminder of a kind of mobility that now feels like a rare privilege.

Today, looking at the other side of the river, it may seem miles away. But is it really that far? From time to time, alternative forms of communication can be observed, such as broken conversations between fishermen about their catch or someone pretending to be fishing while smuggling alcohol and cigarettes. And on Midsummer’s Night, a disappearing but magical tradition continues — people on both sides of the river sing to each other across the water.

The centre of Piedruja is small but charming. It has two churches — Catholic and Orthodox, a school that closed in 2009, a local shop, and many beautiful vernacular homes. These days, it gets busy when the truck drivers, who are awaiting their turn to enter Belarus, come here to buy food. If you’re planning a barbecue, be sure to reserve your shashlik early — before the shelves are empty, due to truck drivers. On Sundays, church services are held in three languages — Latvian, Polish, and Russian. Every Easter, after the church service, a tradition called Walking on Alelujah (Staigāt pa Aleluja) takes place, where local children visit nearby homes and are gifted Easter eggs or candies. It is often accompanied by the playing of musical instruments. The Catholic church, rising tall above the trees, is looking across the river towards its sister in Druja.

And here begins the tale of how we might move towards Druja — through a hidden, underwater tunnel, supposedly connecting both riverbanks. I can’t guarantee it exists, but I won’t claim it’s just a tale either. Some say it was built for Polish–Lithuanian nobility or monks. Along its path, the tunnel is said to surface on the island that lies in the middle of Piedruja–Druja, now part of Belarus. Locals warmly remember celebrating Midsummer and Maslenitsa on the island or swimming at the sandy beach. Boats once floated back and forth here, too, just like the ferry.

Druja is where the village was born, when in the 16th century a stronghold was built for Polish–Lithuanian nobility. From there, Druja grew into a small trading town — a middle stop point between Polotsk, Vitebsk, and Riga — eventually expanding to both sides of the river. Incidentally, Druja was considered as an alternative location for a fortress, which was ultimately built in Daugavpils. Imagine how different this place would look today if the decision had gone the other way!

Like many other towns in the region, Druja had a thriving Jewish community — half of the village’s population. There were around eight synagogues, a Jewish school, and several organisations, including a youth group founded in 1925 that prepared members for migration to Palestine as part of the early Zionist colonial project. Today, the community is gone, and many of its buildings were destroyed during the war. What remains is the country’s largest Jewish cemetery, with mossy, old gravestones scattered across the green landscape. It’s assumed that Piedruja also once had a synagogue.

During our research, Druja remains more absent and even mysterious. There is simply less publicly available information, and on-site research was largely carried out in Piedruja; however, people there had many stories about Druja too. Darya visited Druja in 2024 and met a local who is working to preserve the area’s past and frequently helps out the locals when needed. He’s restoring historical buildings, running the Cultural Palace, and organising a summer school for teenagers who help with the renovation of the Orthodox church. It still has a few old stone-paved roads — planned to be replaced with asphalt, until a retired woman protested by lying down on them. Druja also has an artist summer residency programme that takes place in the Catholic church. Overall, Druja is a much livelier and more active village than Piedruja.

Although the political context across the river is different, in Druja people are still allowed to swim and fish, and there’s no State of Emergency as in Latvia, where such a legal framework is intended to prevent refugees from entering. The regime in Belarus wants a humanitarian crisis to happen, and they’re not hiding it. Yet, many aspects on both riverbanks remain the same. Both share similar «twin structures» — historical stones, Catholic churches, and vernacular buildings — along with shared stories of division and long-distance friendships and hope for a future closer together. Like the story of two cousins — one on each side — who eventually stopped calling, locals realise they may never meet face to face again.

Judging by today’s events, division is something that will only increase. For instance, the land along the river in Piedruja is currently being deforested to build a fresh wall next to the river. This will be a «cherry on top of the cake», taking away the water from the locals, an aspect that is important to their life. Moreover, numerous locals have expressed that they will feel like they’re in a cage or a zoo, monitored at every step.

Piedruja–Druja is becoming a fortress, following an imagined line drawn by humans on a map. But unlike the fortresses of the past, this one excludes vital parts of itself. Piedruja–Druja materialises through the memories, languages, buildings, traditions, and waters it holds. It belongs to both banks. Many locals would be happy when fashion returns to tearing the walls down, not building them up. An era when Piedruja–Druja can be experienced as the locals would hope — with an operating ferry in the river and parties on the island.

As a place with a history of being split and reunited, always on the edge, locals see these questions differently from people in the capital. Here, the militarisation and surveillance take physical shape — not just as the news headlines. And clearly, they leave no positive trace when they prevent locals from carrying out daily activities and seeing people important to them. Who wants to live next to a surveillance tower or anti-tank barriers? Who wants to be prohibited from touching the water that is just by their home? Who wants to be unable to visit their family? How can defence measures respect local lives more? How can border towns remain united — even in times of crisis and polarisation?

Borders aren’t simply places where something ends, and something else starts — they’re gradients, where cultures, identities, and languages come together. How could such a village without walls arise and flourish again, especially in today’s political context? When could this happen? What needs to change for the walls to disappear? Would a unified village mark a hopeful, melancholic end or unwanted political change? Or perhaps something else entirely?

Follow the Piedruja–Druja artistic research project on Instagram.

Viedokļi