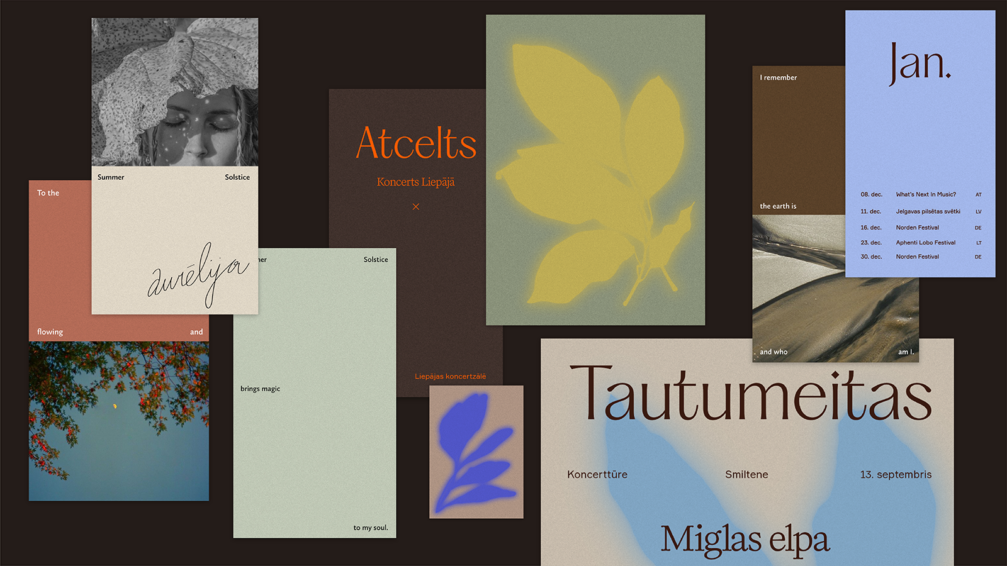

Creative director Dārta Apsīte believes that we need the poetic and the beautiful as much as the practical. Under her leadership, a new phase in Riga’s communication with its residents began — her urban campaigns, both praised and criticised, aimed to foster a sense of belonging to Riga and Latvia, winning several awards. Currently, Dārta is taking on a new challenge and, together with like-minded women, has founded the design and communication studio Ausme.

Your studio Ausme is still quite new, but you’ve all come in with substantial experience. What led you to start your own studio?

It was a coincidence. Although the idea of my own studio had been in the back of my mind for a long time, it seemed that before that I had to gain some experience. Previously, I worked for the Riga City Council, where I had to build my own team—it was basically a small in-house studio. In this job I realised that I like to bring together professionals and thinkers from different fields to develop ideas together and to come up with creative solutions. I concluded that I had a lot to say—I am interested in the search for identity in contemporary design and other creative expressions.

When I left my job in the municipality, I was faced with the choice of working for an agency or creating something of my own. At the right moment, the entrepreneur Egle Klekere approached me and said that if I had the impulse, I should create, offering me her support. I decided to give it a try. I asked Beāte Broka to join the studio—she is a wonderful project director who understands the business side. I handle the creative concept and the strategic direction of the studio, and Beate takes care of business development, running the studio and client relations. Designer Kristiāna Marija Sproģe, who worked in my team at the Riga City Council, also joined us. She has a wonderful and very fresh style, and we think visually alike. A new addition to our team is Lauma Studena, another creative project manager.

We connect, breathe, and sleep with each of our projects and have set our quality bar very high. We work in a small «strike team», but we have artists and designers with their own unique style that we can bring to a fitting project.

What are Ausme’s ambitions?

Firstly, we would like to connect the art world with the commercial world. I think all of us have an understanding of both sides—we understand the artist and the client. We can translate an artistic concept into a marketable quality, which is important. I feel that there is a desire in the industry for something real because people are tired of advertising.

Secondly, in the future I would like to not only serve clients but also create something of my own, gather like-minded people around me, and talk to the public. My sister is studying ecophilosophy, and I’m very close to tradition and mythology. We have wonderful discussions about different worldviews, also in the context of ecological challenges. If we look at the traditional cultures of different cultures, there is no separation between man and nature. This is a conversation that I would like to promote with like-minded people in the wider public. To create research and think tanks, to involve local craftspeople, and to include a poetic perspective on the relationship between man and nature.

So far, your most visible work has been at the Riga City Council, which essentially started a new phase in the municipality’s communication with the city’s residents. Tell us about this experience!

The work in Riga was wonderful in the sense that we had freedom and the opportunity to shape the outcome until the very end. It’s important to me that in any material the essence of the idea is translated accurately. For the Riga campaigns, we created all the material—right down to the Facebook cover image.

When I was offered a job in the municipality by the then head of the Riga Mayor’s Office, Evija Celma, at first I was sure I didn’t want to do it—it didn’t seem like an attractive place for a creative to work. The City Council had just changed management, with Mārtiņš Staķis at the head, and after several attempts at persuasion, I decided to give it a try. The first challenge I faced was a lack of identity. Clearly, it would be too expensive to change the entire visual identity of the city at once, so we started with small steps. First, we worked with Overpriced to organise digital communication, and then the snowball started to roll—all departments wanted to use the new visual identity because no one had a common guideline before.

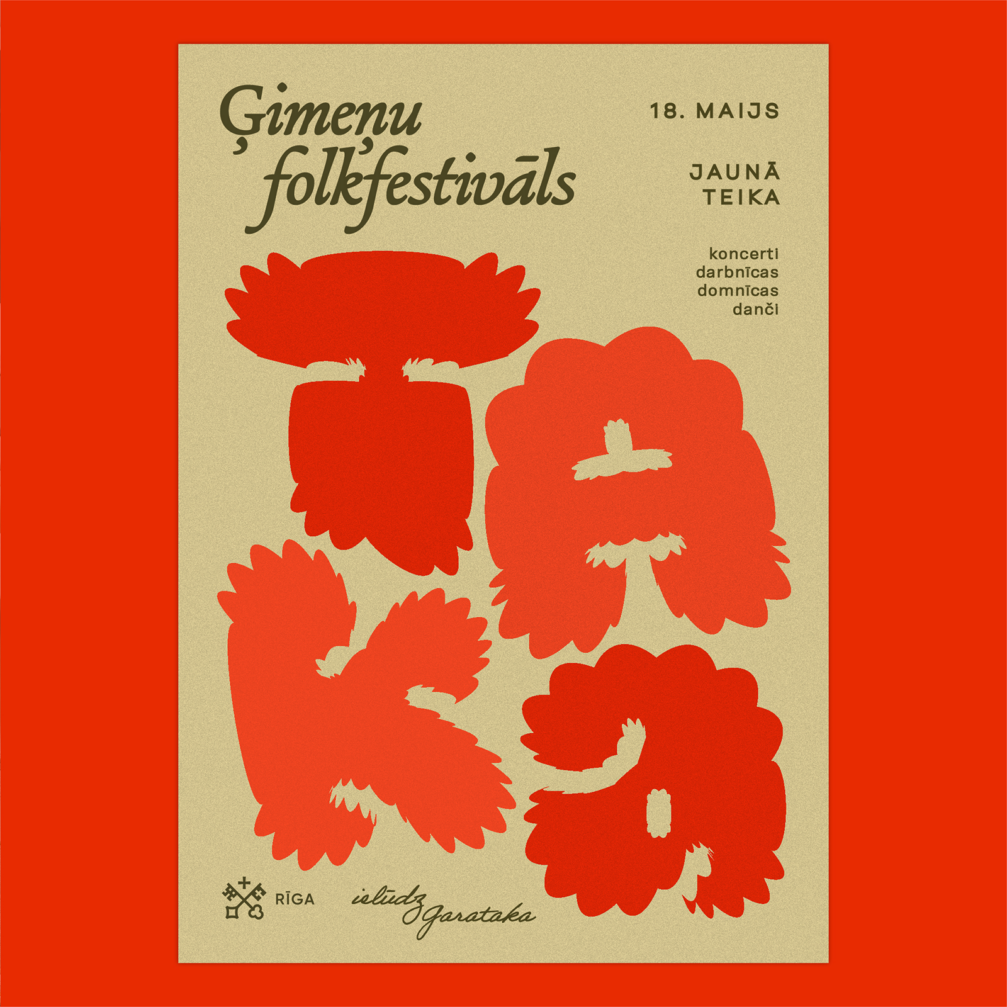

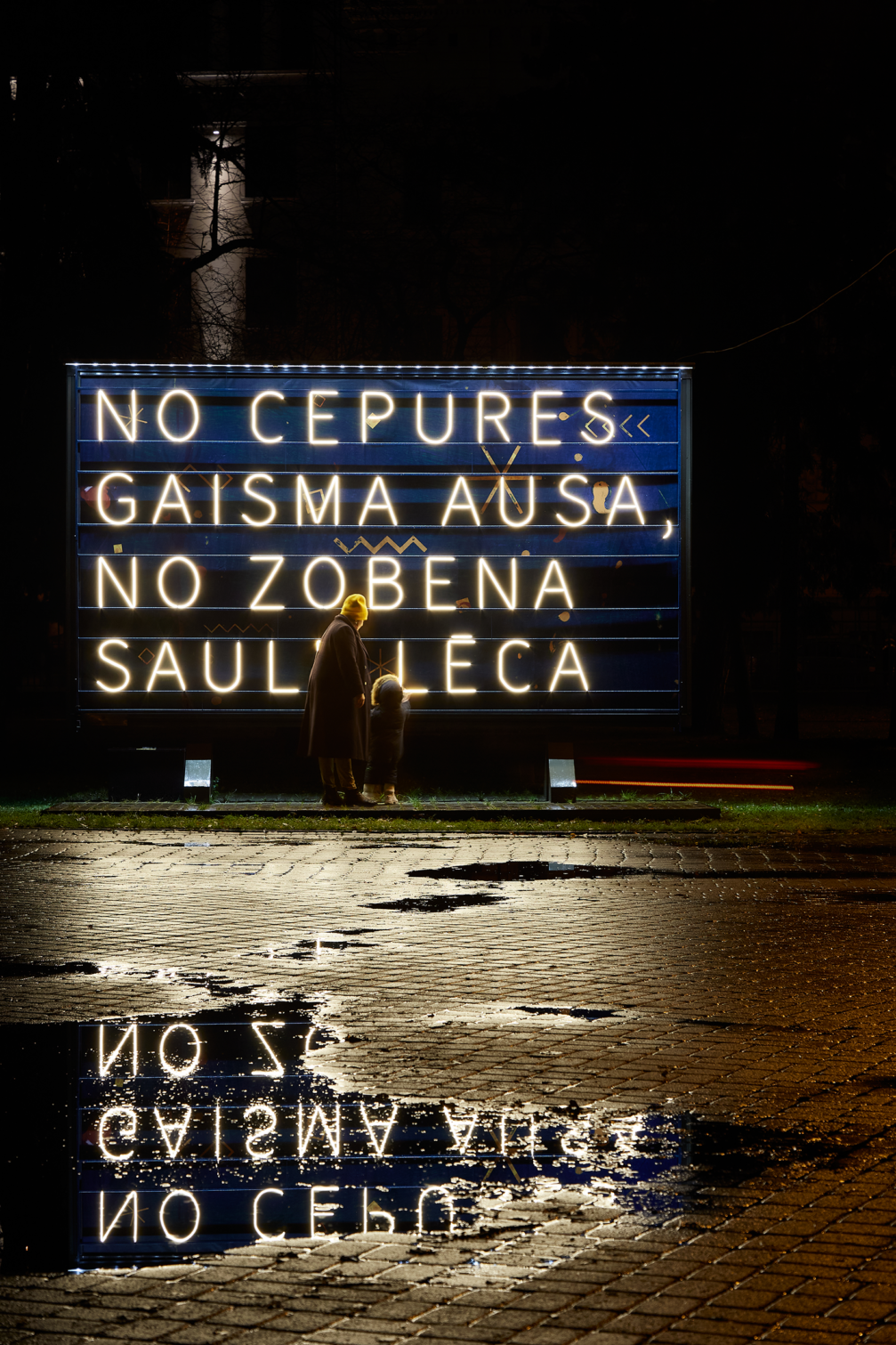

I worked in the Communications Department, where I led my own team. The first urban campaign launched in 2021. As national holidays approached, other departments hinted that we needed to communicate something, but we had neither a main visual nor a concept. It’s clear that a government office doesn’t normally think much about these things, but I felt it was important to present Riga’s communications in a unified way—both in message and in visuals. Thus, the first communication campaign, Raise Latvia with Work, Song, Language, was born, which I developed together with Renāte Lagzdiņa. Artist Paulis Liepa created the festive graphics, while Krišs Salmanis helped with environmental objects—light installations featuring folk song verses. Of course, the campaign’s implementation wasn’t without difficulties or Twitter outrage.

I remember the moment when, in dusk, I first noticed the poster from my window. At first, I couldn’t tell exactly what it was, but it instantly caught my interest. The next morning, in full light, I was delighted to see something truly beautiful on a poster stand! The ensuing public outrage felt so unfair.

That was my first encounter with such a reaction. The City Council had a poor reputation, so people disliked things by default. I wasn’t too surprised by the negative comments. Naturally, there were a few mistakes in the campaign’s implementation, but that seemed inevitable given our one-and-a-half-month deadline.

With a small budget, we created not only the poster but also continued the story through light installations. We felt it was important that the installations be spread across all of Riga—not just in the centre, but also in Vecmīlgrāvis, Ķengarags, and other neighbourhoods. The City Council staff were sceptical and thought that the installations would be quickly vandalised or stolen—but that didn’t happen. We realised that people do need things like this, and everyone loved the illuminated verses.

In the end, the initial backlash helped put municipal communication on the agenda, and we received several awards. When haters appeared, they were matched by just as many supporters. Crucially, the leadership at the time wasn’t scared off by initial criticism and allowed us to continue. That’s why it’s important to have courageous people in power.

I’d like to think that, overall, people did come to love the municipal campaigns.

Not at first. Then came Robert Rūrāns and accusations of «Slavic colours» and that we were cancelling the word «Christmas». However, eventually people began to look forward to our work—there followed the Riga Summer of Courage and Joy and the campaign featuring flags and Knuts Skujenieks’ poetry.

As the next national holiday approached, politicians had grown wiser and waited for us to present our concept. For some reason everybody assumed that flags in the streets weren’t enough—that they also had to appear on posters. Meanwhile, I really wanted to speak about Latvia through various symbols and endeavour to move people. Ultimately, we landed on stories of flags and Knuts Skujenieks’ words. In collaboration with designers Jānis Klaučs and Eva Abduļina, we designed the campaign to be visually minimal, with great respect for the content.This campaign was also recognised abroad. I was pleasantly surprised that professionals outside Latvia could appreciate such a local message.

For your first national-holiday campaign, you received a European Design and Art Directors Club (ADCE) award, and last year, you were judging entries in the competition as a jury member. What was that experience like, and how would you compare our local scene with the works you saw?

Serving on the jury confirmed for me that localised, heritage-based content is highly valued right now, and those were precisely the strongest works in the competition. Europe is thirsty for something authentic. I vividly remember a clip for the Spanish football club Real Club Celta, where traditional music was fused with contemporary street culture. Even in conversations with fellow jurors, I felt how intrigued they were by the idea of locality. It proves that we can confidently take our work beyond Latvia—people want to see what we create. We shouldn’t fear that we won’t be understood; we simply need to tell our story better, grounding it in truths that are universally felt.

You already mentioned that your work aims to speak about belonging to Latvia and foster a sense of community. In your view, what is modern Latvian identity, and why is it important to discuss it?

I believe the Latvian worldview is very poetic. I wish we weren’t ashamed of it—that we didn’t smirk at it as something naïve. It seems that today’s world leans towards realism, but I feel that the beautiful and the poetic are vitally important because they give us hope. They allow us to build an imagined world, through which we can also perceive the beauty in the real one.

There’s constant debate about what a «true Latvian identity» is. I always want to dig deeper and seek that sense of Latvia we hear in folk songs and fairy tales—I don’t want to talk about the mundane but about greater things. For me, Latvian identity is about clarity of thought and a sense of beauty, about Latvian ethics and aesthetics, and our strong work ethic. It’s humility towards nature and our fellow humans and our ability to speak in symbols.

Could one say that the profession of creative director is, in a sense, a means of self-expression for you?

Yes, without doubt—yet I certainly don’t consider myself an artist. Lately I’ve had an internal debate on this point. An artist expresses themself no matter what; in advertising and communication, however, you must adopt the client’s ideas and objectives, so it can’t be purely individual self-expression. At the same time, that individual creative vision and signature style allow you to bring surprise into brand communication. That’s probably what differentiates studios from agencies: while large agencies can provide full service and fulfil every client’s wish, studios offer their own signature style. I think in the future the boundary between artistic expression and communication design will blur even more.

In my work, I feel drawn to combine the traditional with the contemporary, to explore mythic worldviews, and to work with music. I look for intersections between music, art, and communication to reveal my perspective on things. I’m deeply moved by the poetics of music, art, and traditional culture. I feel I can translate those highly conceptual ideas into something accessible and engaging.

You are not only a creative director but also a music-video director. What drives you to try out various creative disciplines?

I’m still searching for my path. The older I get, the more I feel I know less—that I must keep learning. There was a moment when I felt I had to choose between working in advertising or studying directing. When I had decided to leave communication behind and pursue directing, I was offered the job at Riga City Council.

Nevertheless, the video format remains very close to me, and I enjoy working with various audiovisual media. Music is also crucial to me—every clip I’ve directed, not just music videos, has been built around music.

I’ve collaborated on several music videos with the band Tautumeitas, where tradition and contemporary context come together very directly. When we conceptualised the video for their Eurovision song Bur Man Laimi (Bring Me Happiness), we wanted to speak through a mythological worldview understandable to European nations with ancient histories. We delved into myths and folktales and landed on the motif of the hollow tree, which appears in many cultures. Crawling through the hollow is symbolically an initiation and transformation, emerging into another parallel space and becoming something new. The Latvian world from which our fairy tales, legends, and folk songs spring is alive and pulsating, full of light. A person living in such a world is never alone.

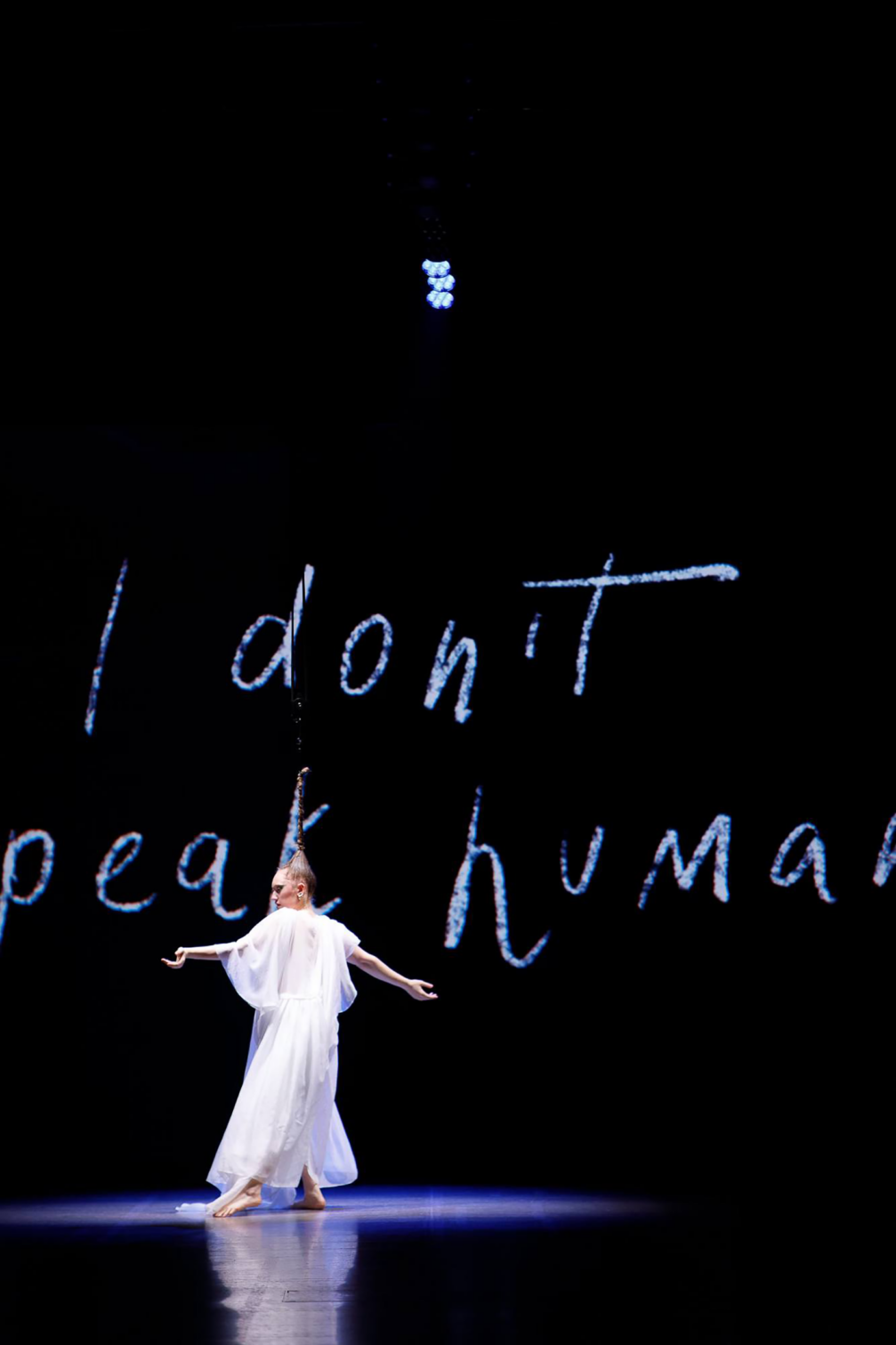

Just a few weeks ago, Ausme made its debut at Riga Fashion Week in collaboration with fashion designer Laura Anspoka’s brand Novaliss, helping to bring the creative concept of the collection I Don’t Speak Human to life in an audiovisual format. Here we developed an absolutely wonderful collaboration with musician Evija Vēbere, with whom we created the show’s soundtrack. That is perhaps the most beautiful aspect of our work—meeting like-minded people who inspire and move you with their vision of the world.

Which of your works are you most proud of?

My favourite works are, of course, those connected with Latvia. I particularly loved the Knuts Skujenieks campaign because it was so pure. I liked that we could speak through text alone without having to entertain people. I also treasure the Riga Midsummer campaign we made in 2023 with photographer Jūlija Sinka. I had seen her work on Instagram and thought it would be so lovely to weave Riga into a flower crown! It is a symbol of protection, but I didn’t want to place a literal flower crown on the poster; I wanted the wreath to surround the whole city of Riga.

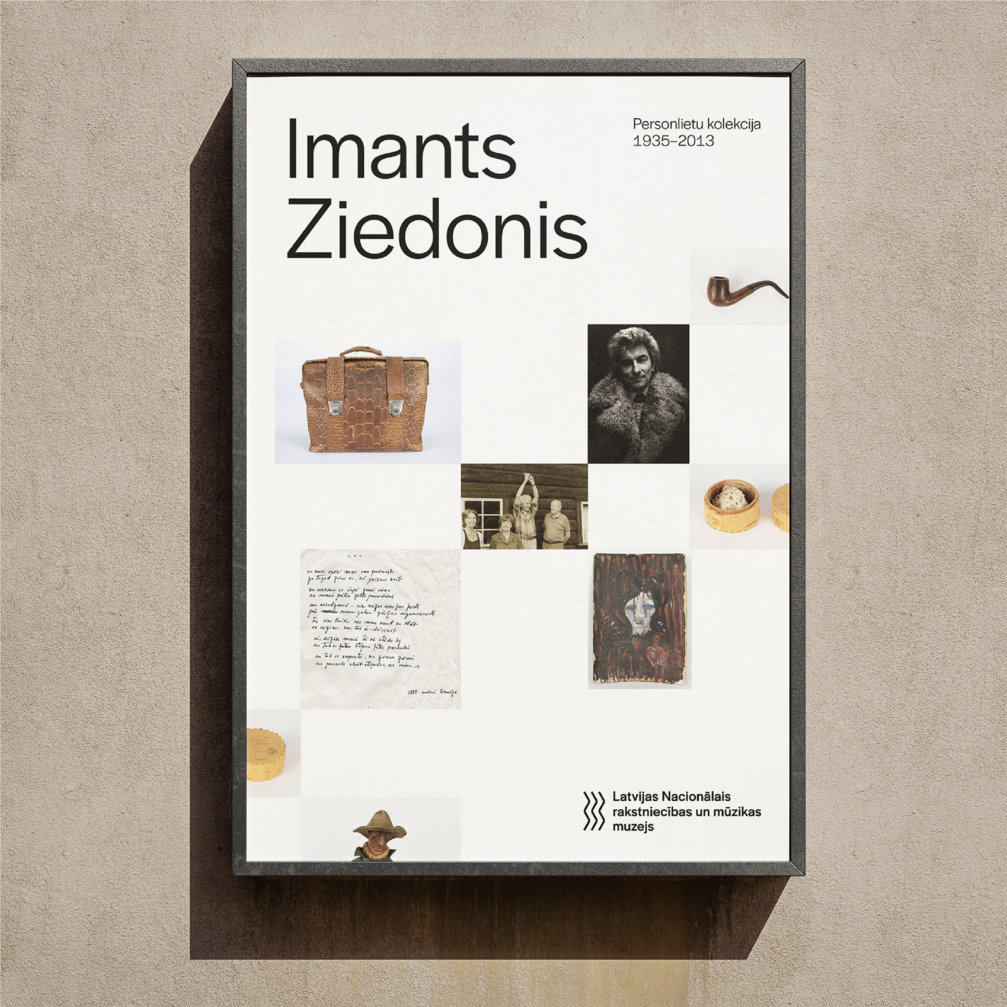

Ausme also recently completed the rebranding of the Latvian National Museum of Literature and Music, focusing primarily on the digital realm. As part of that project, we were able to immerse ourselves in and research the museum’s founding story, concluding that it has always been a trailblazer—different in both form and idea. That is what we sought to emphasise and highlight.

You can follow the creative work of Dārta Apsīte on her website and Instagram account.

Viedokļi