Board game publisher Brain Games dates back to 2004, when it brought Settlers of Catan to Latvia. The company localises board games in the Baltics, oversees game stores as well as publishes and distributes its own games worldwide. Egils Grasmanis, CEO of Brain Games, has been with the company since the beginning and has been involved in each of these areas.

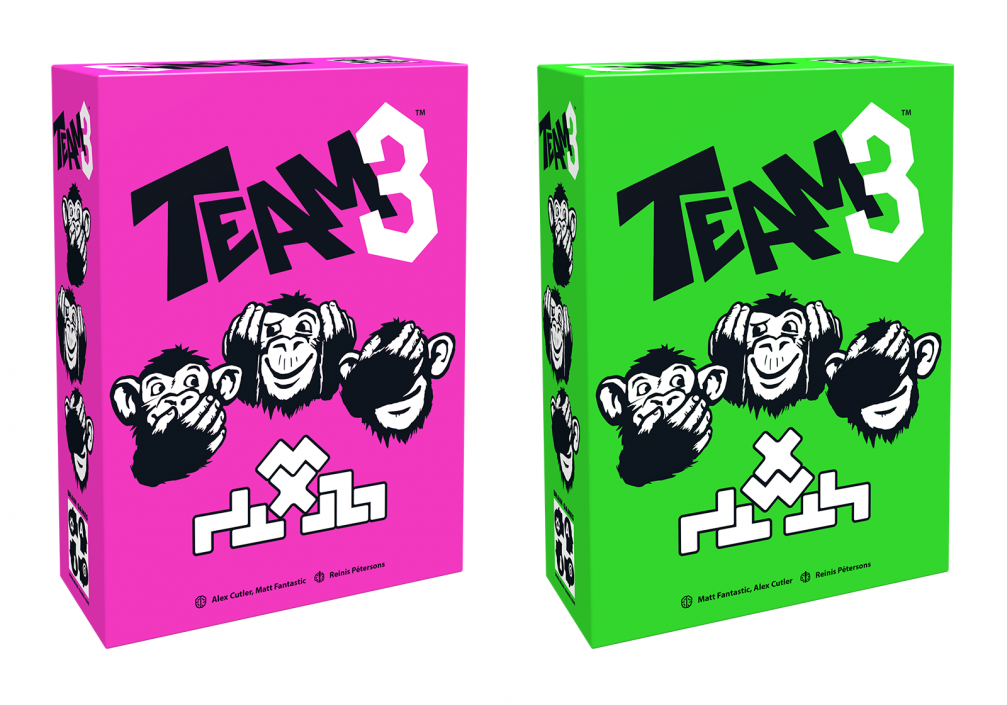

In 2017, he took the stage at Spiel des Jahres to receive the award for the best children’s game. After winning the prize, IceCool quickly became popular with children and adults around the world, creating a powerful platform for future editions of Brain Games. The most promising of these is Team3, released this autumn.

Even before Team3 came out, you mentioned in various events and interviews that it would be Brain Games’ next big game. What gave you the confidence to say that?

When we meet with our international partners, we show them the games we are working on and the games that we are planning to release in the next 1–2 years. We take into account their reactions and level of interest, this is the first signal. Regarding Team3, everyone was pretty sure that the product was simple enough and unique enough to succeed. From these first signals we figure out which game would be the favorite of the year, and we reinforce our efforts at the development stage, invest more in the top product, however sad it may be for the authors of the other 3–4 games.

The board game market is saturated. We just returned from Essen (Essen Spiel 2019 — auth. note) where we saw over 600 new games. Although the largest, it is only one of many industry exhibitions. There are thousands of new games every year and in order to stand out, the game must have unique design, mechanics, packaging and materials. There were many versions for the cover design of the Team3 prototype, and there was a lot of discussion. For a moment, it seemed like we were already grinding it too much. I would say that what we did was quite bold — we wanted to be different.

So you present to partners about five games you have chosen to publish in a given year. What’s the work put in before that — how do you get to the five?

Game ideas are sent to us on a very regular basis, with an average of 1–2 ideas per week. Even this morning, an Italian author messaged me on Facebook. We, as a publishing house, have made ourselves quite well known internationally.

The first step for us is to read the rules or watch the video and see if this is something unique enough or if we can add something to make it unique. About 10% of the games make it through this filter. Then we ask the author to send in a prototype. When we get the game, we put it up for playtesting. We look at how the testers have rated it, and then we filter out some more. We continue playtesting the remaining games, play them with our staff. We then proceed with signing a contract with the author and start thinking more concretely — what the target audience is, what the price of this product should be, and then materials, design, theme come in — everything is put together.

How big are the changes in the design process — both in terms of game mechanics and visual design?

Professional authors have usually put in enough work to make sure that what they submit to the publisher is clear — both in terms of rules and mechanics. That’s the key — if you have unique game mechanics that work, things are easier. But there have been a couple of cases when we have signed a contract and after a year and a half of development, we realise that we have tried to change the game so much that it is better to give up this product. We involve the authors in the development process, sometimes ask them to test something, improve the gameplay. There are also products that are perfect right away.

The only rookie this year is the designer of Farm Rescue [Harris Tsagas — auth. note] from Greece, who had never released anything, but we signed the game an hour after playing the prototype. We changed Farm Rescue a little bit in terms of components, improved a little. The author was very involved in the process. When we first demonstrated the game in Birmingham, he came and presented it himself, and now for Essen, he had also made a farmer suit for himself.

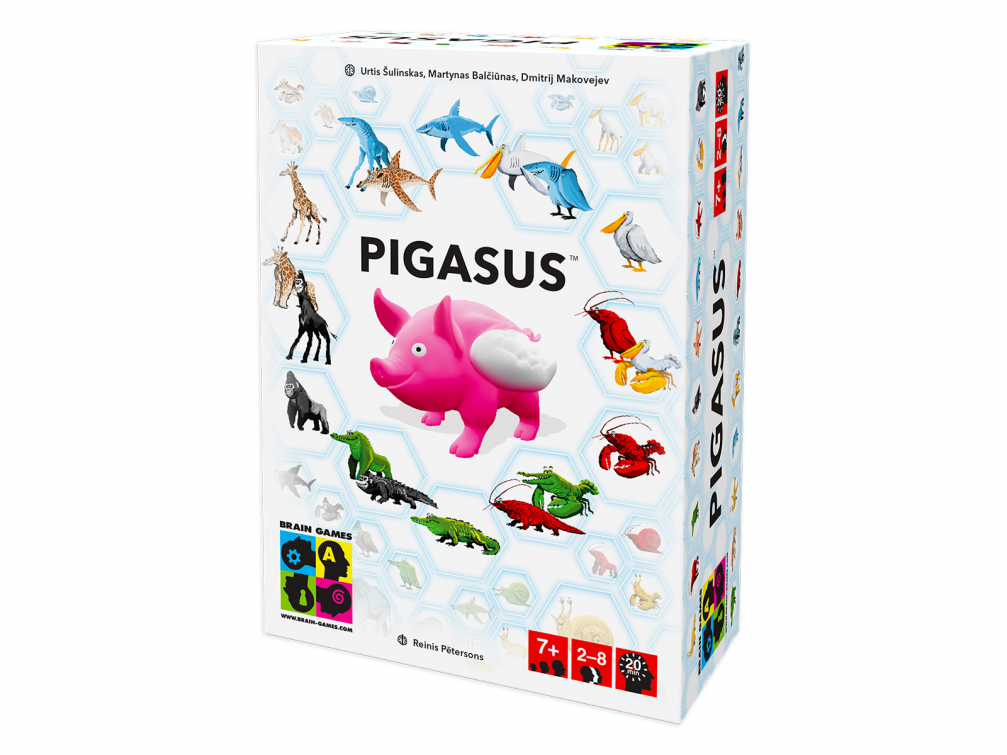

The rest of our games are works by well-known authors in the industry. Pigasus is by a bunch of Lithuanian authors, of whom the main one is Urtis Šulinskas. He is the most prominent board game author in Eastern Europe or at least in the Baltic States. We’ll definitely keep hearing about him, he’s a rising star, also nominated for a prize in Chicago (Toy & Game Innovation Awards — TAGIEs — auth. note). Team3 is by a duo of authors who are well known in the board game industry. Mike Elliott who designed Snowman Dice is a living legend. This is his first children’s game and he has put a lot of trust in us. If we didn’t have Team3, then Snowman Dice would be our number one game right now.

For all of this year’s games, illustrations were made by Reinis Pētersons, with whom you have been working for a long time. What is important for board game illustrations and what makes your collaboration so successful?

First of all, Reinis likes games, so he can delve deeper into the product than many others. Reinis is very talented as one can see by his work. He picks up very well what we want and is able to carry it out in many ways. With this year’s games we have been successful in making the games’ design and illustrations relevant to their target audience, and this is very important. In the past, we paid less attention to it. Om Nom Nom, for example, has good illustrations, but they speak to a different audience than the game mechanics. Targeting and customising your game design and illustration are key to a successful product.

Most games by Brain Games have tactile elements — in IceCool it is the penguins, in Team3 — the shapes, in Pigasus — the squishy toy. How do you deal with this material design side?

The tactile character is what distinguishes tabletop games from online and mobile games. It would be very difficult to convert IceCool and Team3 into an electronic environment because they are physical products. Creating such a product is not complicated, but it is more expensive. When designing Farm Rescue, we had a choice between making cardboard shapes or fine plastic miniatures. We chose the minis, and this meant that the price of the game would exceed 20 euros, which is the threshold for children’s games. Now, after the Essen exhibition, we have realised that in a number of countries we will be releasing the game without miniatures — our partners can choose whether they go for them.

The choice of materials is made in very close cooperation with the manufacturer who is highly experienced. We describe what we would like to have, the manufacturer makes and sends us a prototype, we feel it, test it, and give feedback on it, and then they make the next prototype. Obviously, we would like these products to be manufactured in Latvia, and we did that in the first year, but that’s not realistic, because then we have to become a manufacturing company. We work closely with the RTU Design Factory, where the first penguins were created, as well as other creative people in Latvia.

Brain Games has successfully emerged in the children’s and family gaming segment, where the Kinderspiel des Jahres prize for IceCool in 2017 has probably played a big role. Do you like to be put in such a box yourself?

We haven’t deliberately put ourselves into this box, and you’re right that IceCool played a big part in it, in particular, the small fact that we added a penguin theme to it. By its gameplay alone, IceCool might have been an adults’ game.

How did you come up with the topic «penguins at school»?

As soon as we started sliding the figurines on a table. Who else slides like that? It was pretty obvious that they were penguins. In the beginning, there were gates set up on the table through which figurines passed. But the penguin school came after the boxes appeared. And this is a theme that is more appealing to children.

Mostly we publish kids games, true. But we want to change that with our next project, which we plan to launch on Kickstarter next year. This will determine how successful this game can be. It’s going to be IceCool for adults, with similar mechanics and boxes. There will be boxes on two levels, and you can jump from top to bottom with figurines — mechs. We have showed this game at the biggest shows in North America and also in Essen, there is a lot of excitement.

Don’t you risk losing your existing focus and thus your partners’ interest?

We are still a small publishing house, and we need an assortment to appear somewhere as publishers, we can’t do without it. For example, in 2015, when we felt we had two unique international products, Logic Cards and IceCool, we did not transfer [distribution] rights to anyone else in the US market. We decided that we would try to launch our own brand in the US and opened a company there. It was a bold decision that strengthened our brand, and now we can hand over the distribution to someone else.

Much like we represent the Settlers of Catan in the Baltics, most of our international partners are local publishers to whom we transfer the rights to publish one of our games. In Japan, for example, we have four partners, each of which publishes a different game.

How much of your day-to-day work does it take to find partners, bring products to new markets?

We are no longer actively looking for partners because we already have contacts everywhere. Of course, there are markets with enormous potential, say India, where board game cafes are booming right now. This is a big, uncovered market not only for us, but for many other board game manufacturers as well.

We meet and talk to publishers and distributors at major trade fairs, and it is important for us to showcase new products. In Essen, we had meetings every half hour for 4 days and there were many people that we weren’t able to meet due to time constraints. Finding partners is not as difficult as creating a good product. If you have a good product and a good price, then everything falls into places.

Brain Games has been nominated for the Best Marketing Campaign in the Chicago Toy & Game Innovation Awards. What is your approach to marketing?

In the IceCool campaign, we gave away a trip to Antarctica. It is a travel destination I have long dreamed of, and it is not a place one could easily get to. People had to send in videos showing a creative use of IceCool penguins, and then the best video got a trip for two to Antarctica. A total of 252 videos, mostly from the US and South Korea, were submitted and the contest was won by a US citizen traveling to Antarctica in December.

But when it comes to the campaign itself, I can’t say it was successful. It was pretty wild but unfortunately did not deliver the results we were expecting. I think we didn’t implement it properly, we are still learning every step of the way.

Are there other marketing techniques that may be more commonplace but work?

Most important, of course, is the opinion of the board game reviewers about our games — just like critics’ reviews or organisation awards are important for books and films. In board games, these are mostly video reviews — they give credibility and a desire for people to buy the game.

Social media activities and campaigns that motivate FLGSs (friendly local game stores) are also definitely not to be missed. If they like the product, they will open the box and show the game to buyers. If the game is on a shelf at Barnes & Noble or Target, that is not enough. The service is missing there. As a publisher or distributor, we need to make sure that FLGSs care about us. This is done by sending free copies or by organising in-store game plays. We should understand that well because we have such shops ourselves.

And finally — how do you see the future development of Brain Games?

Two or three years ago, we set a goal of investing more in the creative publishing process. We could do a lot better if we thought more about that, but our attention is too focused on sales right now. Ideally, we would like to become a studio that creates and publishes games, spending less time on sales. We may also be designing games for somebody else — we’ve been approached by a number of bigger industry players who might be interested. We are also looking at additional directions, which could be other games, not just board games.

Viedokļi