Ever since 2010, when the multidisciplinary British collective Assemble made their debut in the architectural media with the inventive self-built cinema The Cineroleum, their works have continued growing both in scale and in recognition. The Turner Prize, awarded in 2015, made Assemble known beyond the architecture circles, drawing the general public’s attention to questions that are at the core of their practice: doing meaningful projects with local communities, keeping up traditions of craftsmanship and making things by hand, creating places and spaces with a purpose.

One of the founders of Assemble, architect James Binning, recently visited Riga to take part in the event series Kompass by Free Riga, and I had the opportunity to find out everything I’ve always wanted to know about the practice.

Do you usually introduce Assemble as a multi–disciplinary practice or an architecture practice?

I tried to describe it to somebody recently like this — we have three different approaches: we design buildings, we set up organisations, and we try to develop models or systems to address a lack of provision in the city. It could be a lack of provision of housing or workspace, or educational facilities, or healthcare facilities. Our job is to look at where there’s a lack of provision, identify a need, and design a response. Sometimes that response is a building, and sometimes that response might be a public awareness campaign or an invitation to an event which helps people to see something they’re already familiar with differently.

Probably 60% of our time is spent on architectural work. The majority of discussions that we have are around building projects, and then there’s a certain amount of time spent thinking about new programs, trying to write briefs and thinking about ways to make these briefs happen — finding sites, speaking to the city government about what we think could improve the mix of things happening in the city or a particular area.

You write the project briefs yourselves?

It isn’t such a common occurrence that the conditions to make good architecture are laid out in the brief, generally speaking. Often, lots of things are already fixed by the time a project lands on the table, so trying to work on stages even earlier than this feels critical. In the UK, procurement generally favours bigger practices and excludes smaller ones. So it is worth to invest some of the time in setting up better conditions to be able to do good projects which serve a purpose and are responsive to what the city needs. You can’t expect someone else to write briefs which you think are good and intelligent and see the situation as you do because you may be the only person who has all the skills, who understands the complexity in realising the project, the costs that are going to be involved, and the bigger opportunities behind this one piece of land. So, instead of investing resources in a design competition stage we invest them in business planning and setting up a development approach for a site.

How did you come to the realisation that you have to take a more proactive approach, to be more involved in the areas that usually aren’t the architect’s responsibility?

Quite incidentally. In our first projects, we didn’t have a lot of money, so we did everything ourselves. Quite quickly we realised that it’s not that complicated to take responsibility for building something yourself. If you’ve done the drawings and you’ve worked everything out, you have a greater amount of knowledge about the task at hand than a contractor who is looking at your drawings. You can call up somebody to get the price of materials and you can work out roughly how long the construction is going to take. Once you’ve done that a few times you feel a bit more confident, you actually know what you’re talking about, and the contractor isn’t doing some kind of magic that you can’t do yourself.

It’s the same with developing or business planning. Doing basic financial modelling or developments is not beyond the capability of most people using an Excel spreadsheet. It just feels like there’s value in taking on and having control over those elements of projects and then choosing where to give them away rather than the default, which is that these aren’t your responsibility at all. Fundamentally, architecture is a multidisciplinary practice — you have to understand economics, politics, sociology, structures. Architects are very well equipped to contribute to other areas that shape the design and set the bar in terms of a project’s ambition.

Can you tell me about the stakeholders involved in the Granby Four Streets project in Liverpool?

Historically, Granby was a reasonably affluent area with a very diverse community, and good quality housing that was built in the late 19th and early 20th century when Liverpool was a thriving city with a large port. By the 1960s, the city was much poorer, and there were parts of it that became very deprived. There was some civil unrest and that resulted in a number of communities, including Granby, being targeted, with tenants of social housing being moved out and distributed across other parts of the city. This left a lot of buildings empty, and the area suffered. More recently, there was a Government programme to demolish all the houses and rebuild them at lower density — the commercial strategy wasn’t to increase activity and to make it a more desirable place to live, it was just to clear the ground and rebuild the number of houses that the market demanded.

But a group of residents who owned their houses (rather than renting them as social tenants), wouldn’t sell them to the Council. So it couldn’t demolish all of the streets, although they did demolish quite a lot, ten of the fourteen streets in the area, I believe. At some point the Council even stopped collecting bins and providing routine maintenance to the neighbourhood, a cynical and aggressive effort to get people to abandon the area. But instead that encouraged the residents to try to reclaim the streets and to take control of the space themselves. Over time, they started to lobby the Council to give them control of the abandoned houses that were in a pretty bad condition, to set up a local market, to actively challenge the perception of the place which was still largely influenced by its tumultuous recent history. Eventually this group of residents formalised as a Community Land Trust, which is a bit like a nonprofit company. They got the Council to transfer the land into this Community Land Trust which meant that the house prices would never go up that much because the land value is fixed — meaning speculations wouldn’t be possible. Usually the value is linked to the local income level, and there’s a process of qualification to get access to the housing.

What was your approach to this community-led development?

It made sense to save what was already there because the quality of the urban fabric and the symbolic value of the buildings was so much greater than anything that could be built to replace them.

It’s an incremental plan, holistic but patient and capable of accommodating changing circumstances and responding to new opportunities. Refurbish some houses, think about how to reintroduce some businesses to the high street, think about the public spaces, opportunities for the local economy, jobs for the local people. Small bits at a time. Everything is quite responsive to a particular need or ambition, involves building a relationship and making a space which can support that need. It’s a project in which many more people have a stake in.

At the scale at which we’re working it’s as important that people feel a sense of ownership and authorship as that the building itself is good and does things well.

We’ve done ten houses now, and there’s a strategy for the whole area. Those houses that are in the worst condition, too expensive to refurbish, we’re going to turn them into new shared spaces, a public garden, studio space and meeting room, a new resource to continue to support the gradual transformation of the neighbourhood.

To justify someone having spent twenty years fighting the council there has to be some special element in the architecture. We’re trying to build something that feels both new and reflects the character of what was there before whilst being economical. Our skill as architects is not to create something very refined but to make use of materials which we can afford and just be resourceful, just do the simple things well. Often it feels like we’re just builders, really. These are decisions that any practical person would make, and there’s not necessary much artistry in them. But then each house also contains a set of small, highly considered elements which give the houses a character and a level of craft in their construction that is distinctive — cupboard handles, kitchen surfaces, a reconstituted stone fireplace made from rubble found around the area that forms a centrepiece in the living room of every home.

How is the refurbishment financed?

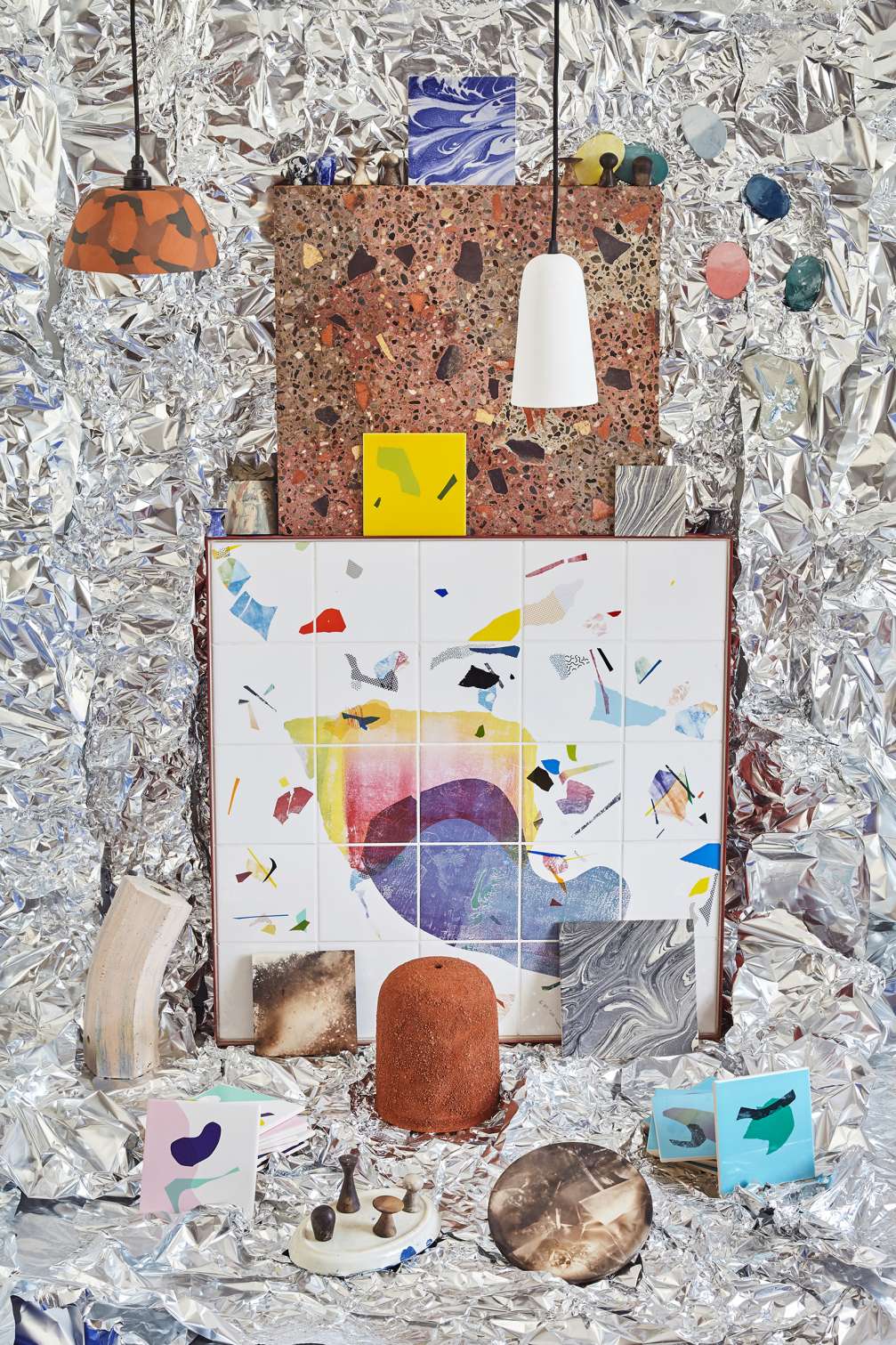

A mix of grants and some social investment, which gets paid back at a low interest. There are some grants available for community-led housing, Government grants provided to support small businesses in deprived areas. The social enterprise Granby Workshop, the ceramics studio that we started there, was supported through the Turner Prize — we were given an exhibition budget, and we spent it on developing a range of furniture and domestic items to launch the business. The exhibition was a showroom of all the products of the workshop. We kind of tried to use the media attention to promote this business to make it successful.

And has it been successful?

It’s still quite reliant on commissions. It has a close tie with us at the moment — we often subcontract or collaborate with Granby Workshop, if we get a commission, a shop fit-out for example, and we develop an interior product with this social enterprise. It’s a way for the workshop to build a portfolio, to produce new designs and to use our projects as a way of building capacity and technical know-how. The latest thing we did together was 12,000 floor tiles for the Factory Floor installation in the Central Pavilion of the Venice Architecture Biennale.

I have to ask you about the Turner Prize…

Changed my life! (Laughs). What do you want to ask?

Well, when you received it, some celebrated Assemble as the first ever architecture practice to receive the prestigious art prize, while others declared it the death of Turner Prize. What were the consequences for you? What doors opened and what doors closed?

It’s very rare for conversations within the world of architecture to break out of the professional circle and to reach a more general public. It wasn’t very big news in the UK, but it was on the TV, and there was a broader level of coverage than architecture is typically given. For a moment architecture was present in a discussion beyond the people directly involved in the industry.

For us, it meant that our projects, particularly things in Liverpool and Glasgow, were seen by a lot more people. And it was really good that it also promoted the work done by other people involved in those projects, like the legal structures set up by residents, which are becoming increasingly widespread and have the potential to be really significant in the creation of affordable housing across the UK. There were strong ideas in those projects that are replicable, they have the potential to act as prototypes for many other areas of cities experiencing a similar condition.

The people that gave us the prize knew exactly what they were doing — they took the decision that this is a project that can advocate some of the things that were important at that particular time, when severe budget cuts to art funding were happening. People were saying things like — where’s the tangible benefit in the arts? So it was useful to be able to put our Liverpool project in a newspaper and say — the biggest problem in the UK right now is housing, and the people coming up with the best solutions might be artists.

That’s the value of the prize — it’s a tool through which the art establishment are able to give some shape to the public discourse around art practice in the UK.

I think it has had some downsides too. I’ve definitely been told by a couple of people that chose not to give us projects that it had a bearing. Any project that we might get involved in instantly became «that project by Turner Prize winners». But for those community organisations that we work with it is legitimately important that their efforts are seen as their projects, not ours.

When I was finishing up my urbanism studies, I was fascinated by the work of Assemble and other similar collectives, like ZUS, Raumlabor and Exyzt. Yet they almost never hire, making it impossible to join in. Can someone from the outside join Assemble?

We always say — don’t join us, join up with other people. There’s nothing particularly innovative about what we did other than following through on the idea. The thing that we have is a critical mass of people, so enough of us were going in the same direction. When there are enough of you I guess you have a kind of herd mentality, you’re going somewhere and you all assume everyone else knows the directions. A lot of the first things we did were quite naive and born out of enthusiasm and frustrations with the reality of practice. It was a way of continuing to learn and recreating a kind of culture which existed in schools but didn’t feel like it existed in the offices we were working in, particularly at that time, 2009–2010. It was just getting together a group of people that share some interests and are ready to sacrifice some of their immediate personal comfort because by working together you might be able to achieve something unexpected.

Is there any established hierarchy within the group?

We don’t have a director and employees, it’s more like a membership model. We’re all equal partners. People have different roles, but they’re not very specific, quite fluid. There are quite different views on how we could operate, they vary from a much more structured company to complete anarchy. The model is editable — if we think something’s not working right or that we could try working differently, then we have the power to change it. It’s not the default for us that if you don’t like how things are going, you can just leave and go somewhere else because the relationships now are personal as well as professional and so there is a strong sense of mutual responsibility. Whatever Assemble is now, it’ll be something very different in a few years time because it’s a multi-authored vision for a model of practice that is constantly being rewritten.

In a collective of fifteen people, how do you deal with individual ambitions and egos?

I was listening to this podcast the other day, which was talking about lots of things, and there was this one section about polyamory. I think it’s a bit like a polyamorous relationship. (Laughs). It requires a lot of conversation, lots of hearing people out, understanding different ways of seeing the same issues, trying to be aware of the impact of the decisions you’re making on other people’s feelings and opportunities. You have to recognise that some things that you might choose to do other people might disagree with, might not reflect how other people want to work or are best at working. But you all have to trust that you’re pointing broadly in the same direction.

Viedokļi