The past year has been successful for the architecture office Ēter founded only less than four years ago. The day care centre Pērle for people with mental and functional disabilities, designed by Ēter, received the Latvian Architecture Award 2022, while the ASMR exhibition at the Design Museum in London earned the international Dezeen Award for both the best exhibition design as well as the public vote. While balancing the pragmatic and the poetic, Ēter translates cultural and societal processes into space.

Congratulations on the Latvian Architecture Award! What is the aftertaste of receiving this recognition, especially given that you had doubts whether to submit Pērle to the annual competition?

Dagnija Smilga:

Just today I read about the project initiated by the association Latvian Movement for Independent Life, which seeks to raise funding for the creation of a group house for young people with developmental disabilities — the publication referred to Pērle. I am very pleased with both the decision to apply for the annual prize and the resulting publicity, as we have managed to draw attention to social buildings within the context of architecture. I hope to see projects like this more often, because it is necessary for society to grow and develop. I don’t see Pērle as an outstanding architectural masterpiece — if we were to design it now, we’d do a lot differently. But it is an important victory against the overall backdrop of Latvia.

Niklāvs Paegle:

I hope, but I am not sure, that this victory is noticed by the municipalities and decision-makers responsible for the more frequent implementation of public buildings for social functions in Latvia. I have heard the view that Pērle is a very exclusive structure, but it could not be further from the truth. It is important to understand that this is a simple building of a tight budget and other structures created for vulnerable groups of society should also be at least like this or even better.

Kārlis Bērziņš:

The recognition we have gained is important to me because it is a testament that others also understand the social importance of this project, and it is the beginning of a much-needed dialogue. The previous year the award was given to the Mežaparks open air stage — a much more ambitious project, whose budget could cover eighty support centres like Pērle. I’d find that much more interesting because it shapes the common language of society and cultivates the ability to get along with each other. We want to talk about a new type of architecture that is not exclusive but thinks of the society as a whole. If we are able to give the most vulnerable individuals the best we can, we are a strong society.

Working on social projects like Pērle and the nursery school in Garkalne, you have to get out of your own experience to meet the needs of a different social group. How do you balance remarkably high demands on functionality and, at the same time, ambitions for a refined, playful aesthetic?

Kārlis:

In the case of Pērle, the playful style stems directly from a deep understanding of the future users. We wanted to create a special environment rather than a minimal or reduced space that creates a flat experience similar to that of a hospital.

Dagnija:

The project programme and the technical specifications were very pragmatic — we need this many rooms. But if you’re a curious architect, you create more than just a number of rooms. Even the much-discussed terrace — its unusual and flowing form is very much suited to the trajectory in which the customers of the day centre move. The tactile plaster that had caused lengthy discussions with the builder has proven itself to be a direct sensory way for these people to meet the building. We balance functionality and aesthetics — we let ourselves play, and these aesthetic games also work at the level of experience for the user. We’re not afraid of solutions that are not purely practical. Sometimes it is necessary to weigh at what point it is worth sacrificing something pragmatic in favour of the inner poetics of a building. But we are never dogmatic in our approach.

Niklāvs:

It’s a serious game — we have to abide by the budget and the specific demands of the client. We can’t play without a frame, but rather within a limited range. But I try to stick to not taking myself too seriously. Such light-heartedness has given us the freedom of expression and the customer the opportunity to receive the unexpected, to accept it and enjoy it.

How do you manage to find this middle ground between strictly fulfilling the client’s requirements and self-realisation and play?

Kārlis:

We try to get the client interested in topics that we are interested in ourselves.

Dagnija:

Although the construction process of Pērle was difficult, the project was largely about cooperation. Seeing the day care centre manager present the building to the jury of the architecture awards made it clear how much we had learned from each other.

Niklāvs:

Both at university and in practice, I have had the experience of working on projects where it is not a physical location that is chosen as the context of a building, but a particular group or subculture of society, its features, rituals and the material world. In my view, a contemporary architect needs to be a very skilled interpreter. To be able to translate culture into space, a material into geometry, a client’s preferences into real environments. It’s when we translate that we can create value because something new is emerging.

Kārlis:

What Niklāvs calls translation, I call poetics. We live in the most complex time ever, and translation is no longer just a transfer from one language to another, rather a poetic interpretation. You carry something you see on the streets, onto a piece of paper, or take a digital phenomenon back into the analogue setting.

You mix digital tools with analogue models a lot in your work.

Kārlis:

Transferring from nature to a digital model and then back to an analogue model is a method we work with a lot. A model provides a connection to the physical and the spatial. Working only in a BIM environment, you can lose sight of what you create. The analogue medium is important for understanding the poetic concept.

Dagnija:

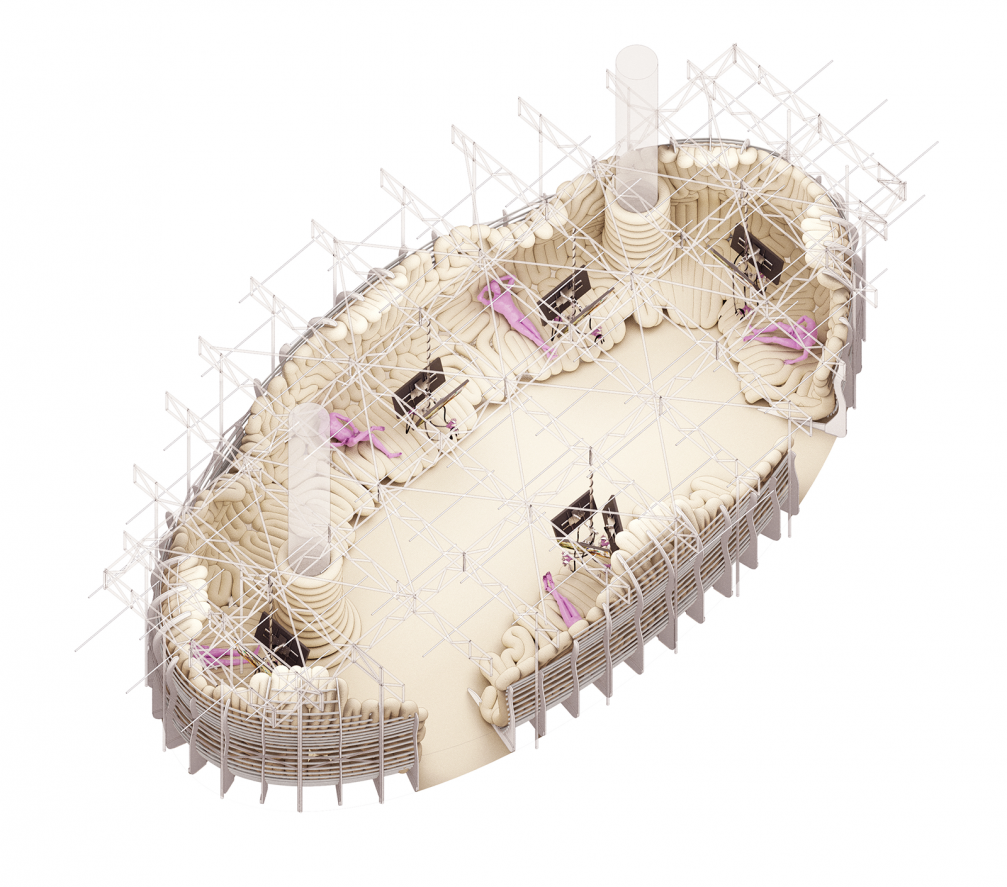

Working on the ASMR exhibition, for example, we realised that the organic shapes borrowed from the lichen world could not be made in a 3D model. Nothing is perfect or symmetrical in nature, and that’s where our interest lies — it was important to us that these sausage pillows had wrinkles and folds like body parts. It is only by experimenting with different materials — by sewing these elements up, or by making them out of clay and then scanning them, can you achieve this effect in the digital environment.

What is your relationship with the digital environment and its tools?

Niklāvs:

With digital tools in architecture, you have to be very careful not to start doing something just because you know how to do it. It’s healthier not knowing how to do it, but finding someone who does. We need the freedom that cannot be achieved by sticking to any particular tool.

Dagnija:

Sometimes I choose not to know how to do certain things because it gives me the freedom to think outside the box. If I’m not a specialist in 3D modelling, it gives me the opportunity to look at a model made by someone else with fresh eyes and see it from a different perspective.

The ASMR exhibition is dedicated to a specific Youtube phenomenon. Are you fascinated and inspired by contemporary internet culture?

Kārlis:

I spend most of my day in a digital environment. The ASMR project taught us that the internet is very diverse and it can also be very creative. It’s possible to play with new trends, bring in phenomena from the material world, forge connections among people. Empathy and feelings that aren’t just empty consumer trends live there, too. The Internet is like a parallel space to the material world.

Niklāvs:

The internet culture of ASMR is largely a generation Z phenomenon. It’s a generation that fascinates us and that we work together with a lot on a daily basis. For me, it was a big discovery that people are seeking this kind of comfort and stimulation on the internet. It was also the main challenge of the project — how do you make the museum meaningful for generations Z and alpha?

Kārlis:

I think the ASMR project is a success because we kept it open to different associations and interpretations. An associative space cannot exist without a user. That’s why we don’t create sculptures, but usable frameworks where we interpret some social phenomenon or group that starts using it, builds their own associations, and participates in the co-creation of space.

Interpretation as a method of your practice also means working on very different, interdisciplinary projects.

Dagnija:

We’re just interested in so many things that aren’t about architecture and we’re trying to bring them all into our profession. For example, I used to sew a lot, and that’s how work with textiles has come into our practice. Our friends and spouses also come from a variety of other professional fields, and we’re inspired by their artwork, photos or attempts to open a gallery. The issues they deal with on a daily basis add to our practice. We also collaborate a lot — around ninety people from different fields were involved in the creation of the Baltic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. It was the source of many important aspects of our work in architecture, including a sense of belonging to the Baltic region.

I have the impression that you are fans of the Baltics.

Dagnija:

We definitely are, because our friends live in Lithuania and Estonia, and we cheer each other on.

Niklāvs:

We actually met outside the Baltics — we had to go to Vienna and London to meet Estonians and Lithuanians. When we met there, we realised we had very similar processes, goals, and environmental problems to think about. The Baltic states are a strong and exotic region of Europe. Ever since the 2014 invasion of Crimea, we have a feeling that we are not alone, but part of something bigger, connected to the rest of the world. By thinking and working through the prism of the Baltic region and the Baltic Sea, we can offer our unique view on global challenges. Compared to Western Europe, we are still only in the early stages of development in many things, and we have the opportunity to learn and avoid the mistakes that have been made there.

Dagnija:

We shouldn’t blindly follow the West, but rather identify what we can do more sensibly than has been done there. We have been in Austria and Switzerland for a long time, where the slowness and heaviness of the system is very oppressive. Although it is a very democratic process, which is good, this bureaucratic weight doesn’t allow to respond in time to environmental and societal processes. Here, everything can be achieved through one person. That, in my opinion, is the greatest value of Latvia. You can build the whole brand of a country on this phenomenon — «Come to Latvia, things happen fast here!»

Now that you’ve returned to Latvia, you have to acclimatise again, get accustomed to the local context, society, builders. Do you ever feel like outsiders?

Dagnija:

At first we felt very much like outsiders, but I guess we want to remain that way, because through our contact with other cities and countries we retain a fresh perspective on local processes. Full acclimatisation is not a goal. At the same time, I would never want to get used to Switzerland. That would also be dangerous because it’s a kind of apathy, too much holding onto established patterns. It seems to me that acclimatisation in a local context is more a matter of being able to communicate clearly with the public and the readiness and openness of society to welcome and understand the new. Very often, the reason processes take place in one way or another here is because the public is not ready to talk about them. In the case of the Uzvaras Monument, for example, it is very regrettable that there was no public discussion between the professionals and the public.

Discussion about the environment is one of the principles for the new architecture school programme that you are creating at the Art Academy of Latvia.

Dagnija:

Yes, the programme has a module called Agency, which aims to be an interface between architects and the public, encouraging open discussion. We would like the public to have a way of thinking about their city, not just through activism and grassroots movements, but through thoughtful, organised conversations as well. There is still a big gap here between architects and the public, as well as a perception that architecture is something expensive and exclusive.

Kārlis:

It’s one thing to learn to draw a line, but quite another to be aware of your motivations and drives for doing so. It takes some time of independent thought and experimentation to become a critically engaged architect. The methods used in art universities can provide that.

Dagnija:

With Agency, we try to encourage architects not just to build homes, but to be thoughtful. To participate, support, and educate through publications, exhibitions, and policy-making.

Niklāvs:

The name Agency comes from the word «agent», referring to architecture as something capable of changing the environment and working within new contexts.

Kārlis:

Traditionally, an architect’s language is that of materiality, shape, structure. But we need to develop the ability of the new generation to engage with society, to be sensitive and mindful of its processes.

Viedokļi