Having started out at OMA, architect Julien De Smedt later co–founded PLOT with Bjarke Ingels and opened his own studio JDS Architects that now has offices in Copenhagen, Brussels and Shanghai. He lives by the philosophy of «performative architecture».

Not long ago Julien joined forces with William Ravn in creating a design initiative Makers With Agendas that was «born out of love for design and their loathing of its abuses» to challenge society’s assumptions on design and speak out on social, ethical and ecological wrongdoings.

You practice «performative architecture», what does it entail?

We came up with the term because all the things we do aim at a form of a performance or an action. It came mostly out of the architecture side of what I do, and there is an intention in our projects to create urban activity and urban life. So «performative» is used in the sense of both the buildings performing in terms of what they provide, and also enabling people to have a personal interaction with them. Mostly in the public space we like to blur this boundary between the built form and the void. By blurring that and enhancing the ways public space can interact with the building and inject its own life into it, we create what we call «performative architecture».

What vision of architecture and design do you wish to facilitate through your work?

Something that enables people to live their lives the way they want. In a world that is extremely contrived into financial realities and regulations, we try to find an in–between spot where things that maybe weren’t necessarily planned or framed can happen. So to create opportunities for activities to occur, find potential and places for life to unfold.

You proposed a rather extreme project of perfomative architecture for a competition to transform the Palace of Justice in Brussels. Why did you enter it if you already felt it would be rejected?

Sometimes you have to make a statement so that people become aware of the need and the potential. The subject of doing justice to the earth hasn’t been really taken on, there are a lot of associations that are working on behalf of the planet but it hasn’t been institutionalized in a governmental way. We thought that this was an opportunity to state that the government should actually wake up and devote the entire Palace of Justice for creating a Palace of Global Justice that would handle cases for the sake of earth and environmental issues. So it was more of a political statement than an architectural one.

What are the main problems of contemporary architecture and design?

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao has introduced the world with iconographic architecture and its power has been very vivid in the past 15 to 20 years. It’s great that it has loosened people’s opinion towards different architecture, but what’s bad about it is that it has created a new standard, an idea that you can make crazy things for the sake of them being crazy or being different. We’re not interested in that at all, we actually despise that. We don’t believe it’s rational or interesting conceptually to approach architecture in that way. We all should be extremely conscious about what we are doing and why we are doing it.

With our work we’re trying to be more conscious about what is important today. The results are looking different but the process is very pragmatic and research–based. One of the problems today is that there is a discrepancy between the easygoingness of people towards design, as if they almost don’t care anymore why design is made, and the fact that the world is in a very urgent need of substance, content and solutions to real issues. As a matter of fact, the real crisis that we are facing right now is not the financial one but the ideology crisis.

What would be those forms of design that people need nowadays?

I think the form of design that would come out if they would listen to their needs instead of just being pleased by designs. This easygoingness towards design needs to be challenged again today. Of course you have to be conscious of consumption, but that shouldn’t mean that you can’t do anything. The typical attitude is «if we don’t have any more resources or means, then we should do the most basic and boring things». And I don’t agree with that.

If you are extremely rational and pragmatic in your approach you can actually end up with a result that is more exciting than the one if you would just use the standards of saving.

Tell us a bit more about the issues Makers With Agendas want to explore!

One of our projects is tackling the issue of natural catastrophes, wars and everything that has to do with the displacement of people. There are around 50 million people that are forced to leave their homes, so we are trying to address this problem by producing what we call the «lifehouse» — a miniature version of a house that can support people and can be just grabbed as you leave. We have also designed a very specific but a very down–to–earth way how to handle mobility in the city by providing the most basic mode of transportation that you can think of apart from walking — the MIKE bike, a gender–neutral bike specially for travels to the airport. We work hard on making all our designs as compact and usable as they can be.

We are interested in creating potential for having a healthier population through design, so we made a Pull Pong Table — three tables in one that can be folded into a dining and a work table and also turned into a ping pong table, so it allows people to exercise as they are at home or at work. It’s combining people’s desires and needs at the same time.

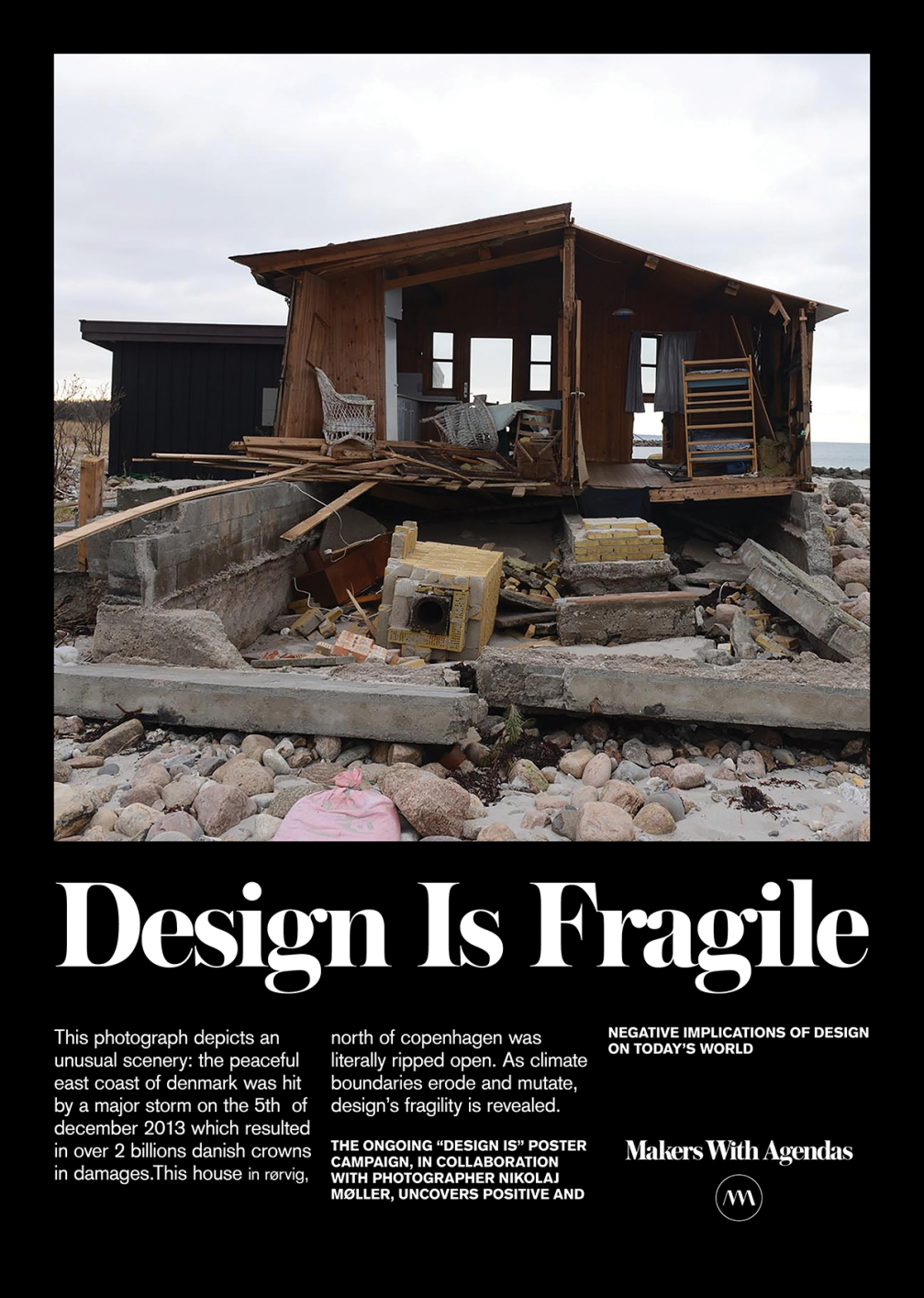

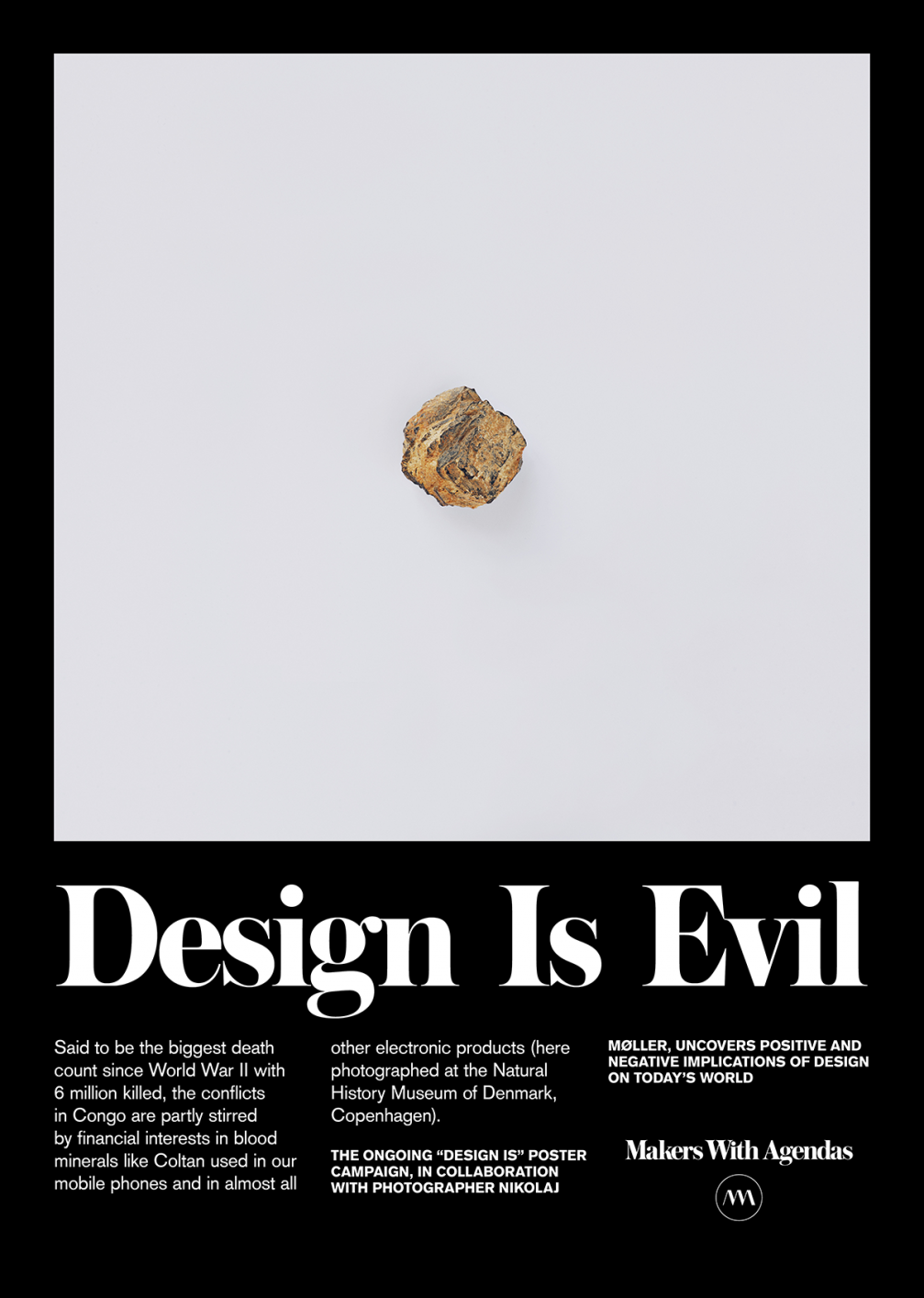

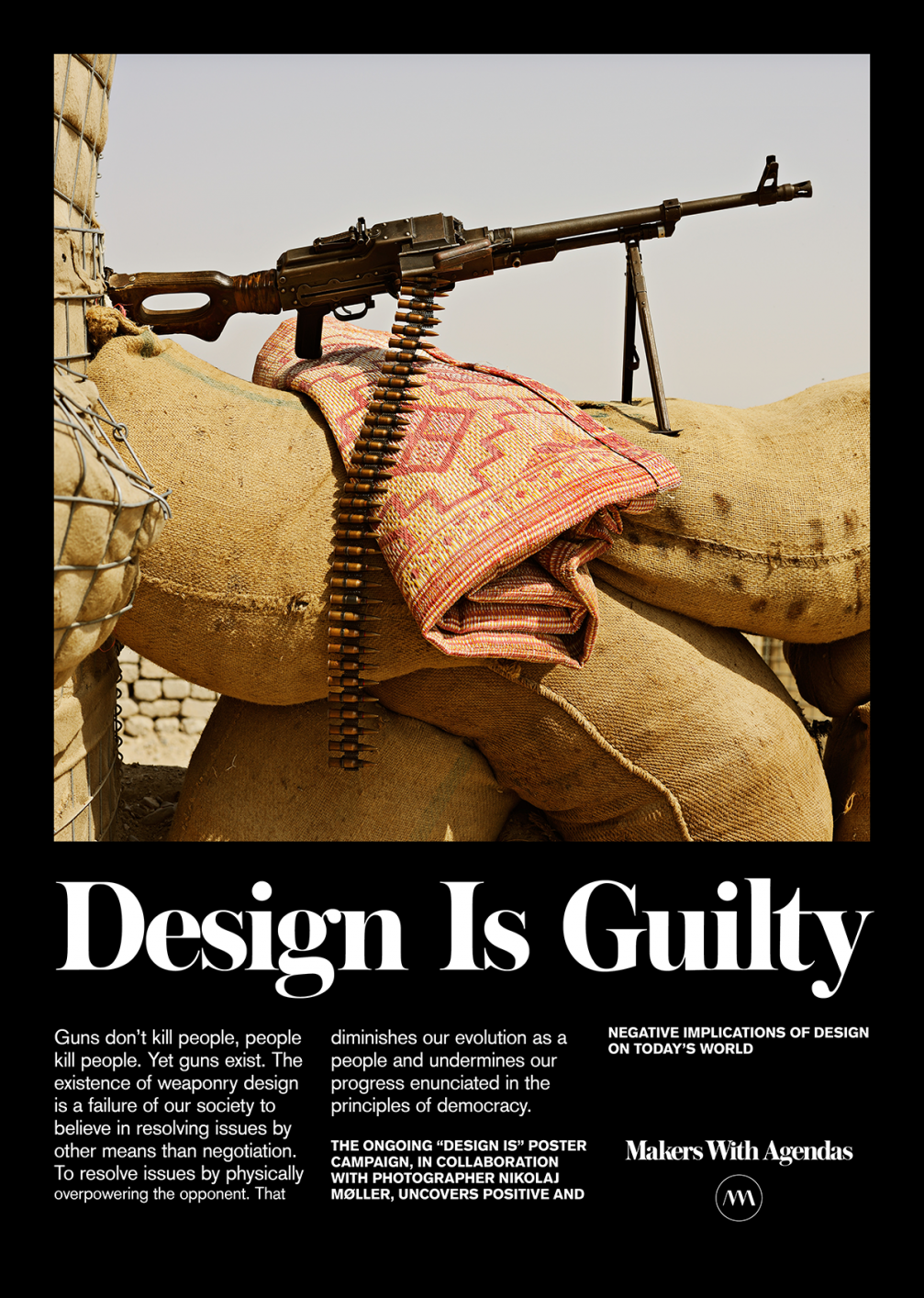

In your poster series «Design Is» you talk about the negative impact of design on our world, how can you as a designer contribute to solving these problems?

The Design Is Evil poster communicates the problematic of using the «blood mineral» coltan in electronics that has caused an enormous death count in Congo. We haven’t yet handled a project that has to do with electronics, but it’s something that we believe is important to address. The moment that we are going deal with electronics, we will have to integrate that also in our company, but we dare to put it on the table already now, even though we’re not there yet.

Commercialism and consumerism are serious problems of contemporary society, so designers have to be very conscious of what they create. How to design a solution and not yet another consumerism product?

We have observed that now more than ever people are victims of the market and they are on a constant move, so there is a lot of instability in people’s lives. We are trying to deal with that as one of the aspects of our approach. We don’t claim to redefine society, we react to society as it is, and I think that’s already quite a job, because very few people actually try to do that. There is a big difference between reacting to trends and reacting to actual facts, because trends are irrational and unreal, they are justified by numbers, not by causes and needs. We don’t care about trends.

For our new collection we did a chair called Pivot. We were very critical about the idea of doing another chair that would just be a part of a production that is actually already answered. But we managed to create an extremely compact collapsible chair that came from the need to have a common chair that would easily disappear until you need it again.

There is a big difference between reacting to trends and reacting to actual facts.

In this abundant environment of product and architectural design, what inspires you to create yet another building, yet another chair?

The needs and reality have changed and the more you are in tune with what’s happening and what’s becoming a necessity, the more you can react and be driven to action. In all aspects of society there’s always something frustrating and lacking that you can answer. Of course we are not claiming to answer everything, but in the world of product design labels we are probably the only ones that care about issues and not about design. We’re not interested in design at all. That allows us to guide our production and projects towards things that matter. Our expression is extremely minimal, we’re not interested in anything scrupulous, and we’re not producing anything that’s unnecessary. People like Jasper Morrison are a big influence to us because of his minimalistic designs, and we want to work in that direction with content and a reason, not just to answer a brief but to create a new brief, a new demand and a new answer to a need.

Is there still an actual chance of being original?

We are aiming at originality but not for the sake of wanting to be original, but out of the sake of dealing with issues that lead to originality.

Just don’t care about being original. If you start with substance and content — that’s what matters and makes you original. Be very understated in the expression of what you’re doing and just focus on what it is you’re doing.

The interview has been created during Iceland’s design festival DesignMarch with the support of The Nordic Culture Point Norden within the framework of Nordic–Baltic Mobility Programme for Culture.

Viedokļi