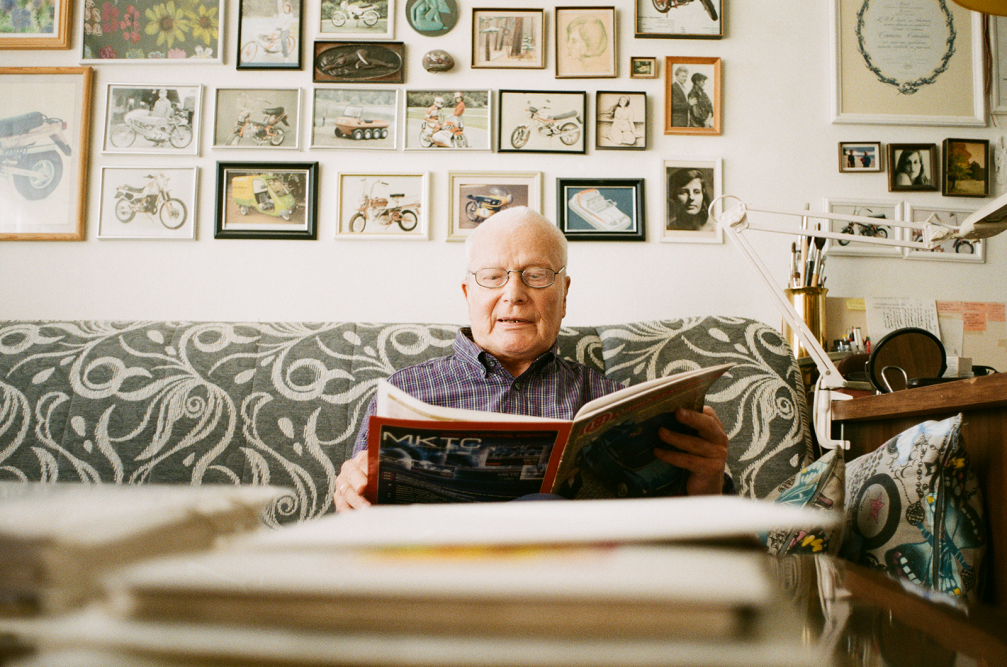

Everyone knows at least one model of the famous «Rīga» moped, while the «Spārīte» tricycle, undoubtedly, was the first vehicle for many generations. Not everyone, however, knows that the design author is Gunārs Glūdiņš who has dedicated all of his creative life to the development of industrial design, either working in the field or teaching at the Latvian Academy of Art, and putting the foundation to the Latvian Designers Union.

«It’s not for me that I collect all these materials and albums. Of course, it’s interesting to go down the memory lane reminiscing what has been accomplished and what it was like back then, but I fear this information could be lost, and there could come people who’d say there was nothing back then,» says the designer Gunārs Glūdiņš (1938) as he is showing the drawings, photos, magazine cut–outs, authorship certificates and diplomas he has been thoroughly compiling for decades. He has put similar care to arranging images of works, alongside his self–painted miniature landscapes and decorated stones that adorn the designer’s living room wall. Speaking of what has been accomplished, Glūdiņš is humble, and with almost every work he mentions his colleagues, especially the constructors. There is a lot to tell and show — for almost 30 years Glūdiņš was the chief designer at «Sarkanā Zvaigzne» engine plant, also doing commissioned work for the State Electrotechnical Factory VEF for as many years.

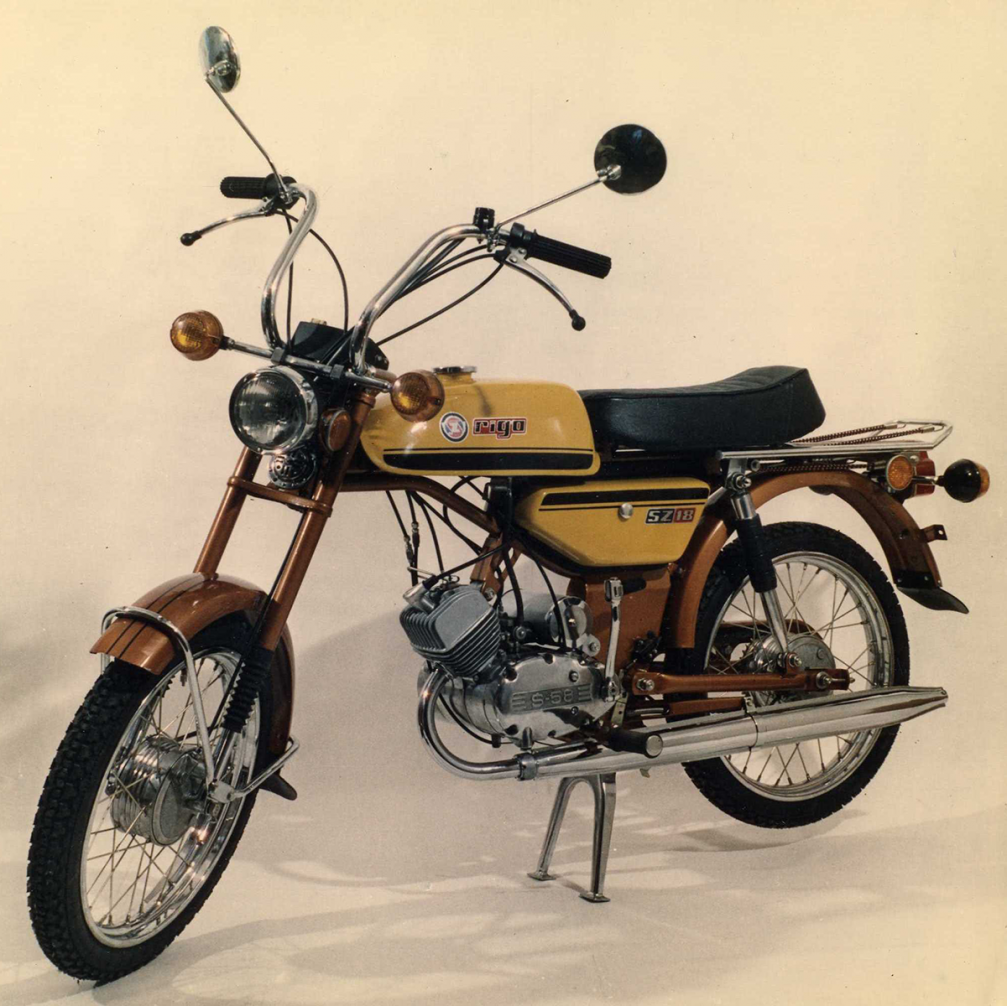

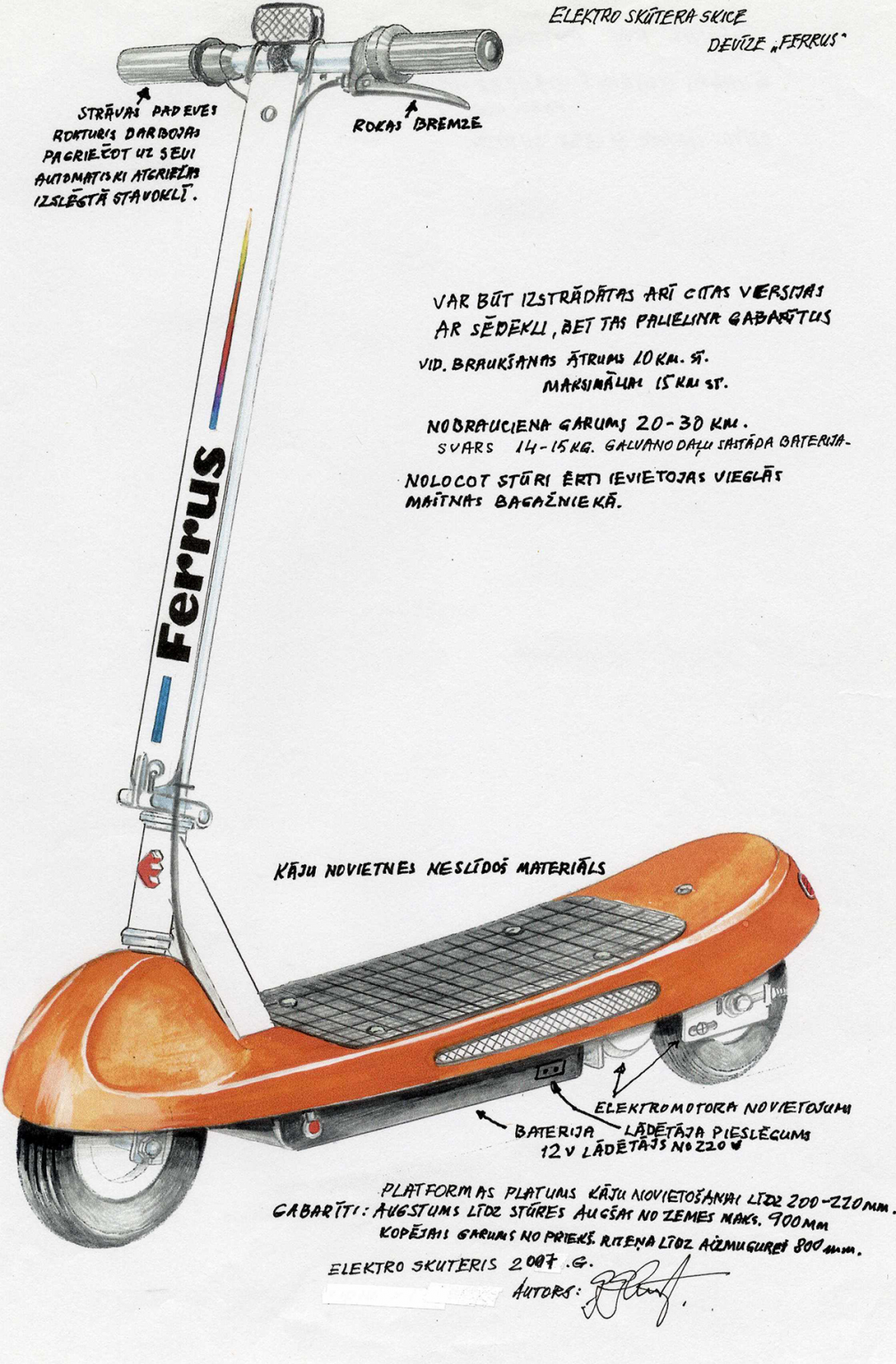

Mopeds «Rīga–14», «Rīga–18», and «Rīga–12», created at the turn of 70ties and 80ties, used to be popular means of transportation in all of the Soviet Union; meanwhile, the latter, as a symbol of the great success of the Latvian motorised vehicle design, has been included in the Latvian Cultural Canon. Despite the fact that in the Soviet times, as Glūdiņš puts it, «the idea was hindered by the reality», many powerful sports motorcycles were built. Marching in front of their own time, together with colleagues, they would dream up new ideas of scooters, mopeds and electric bicycles.

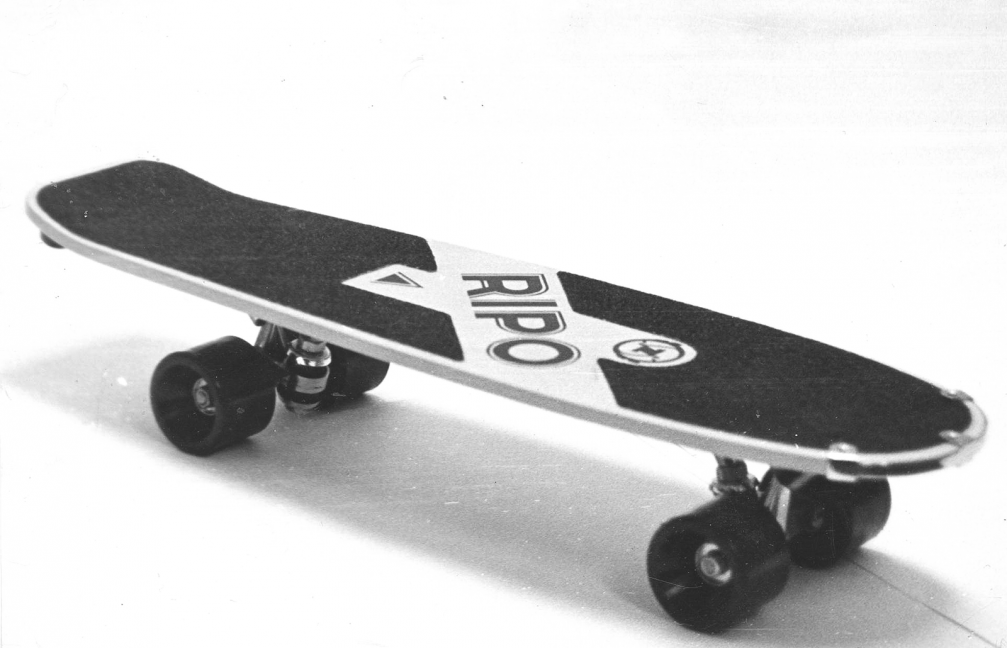

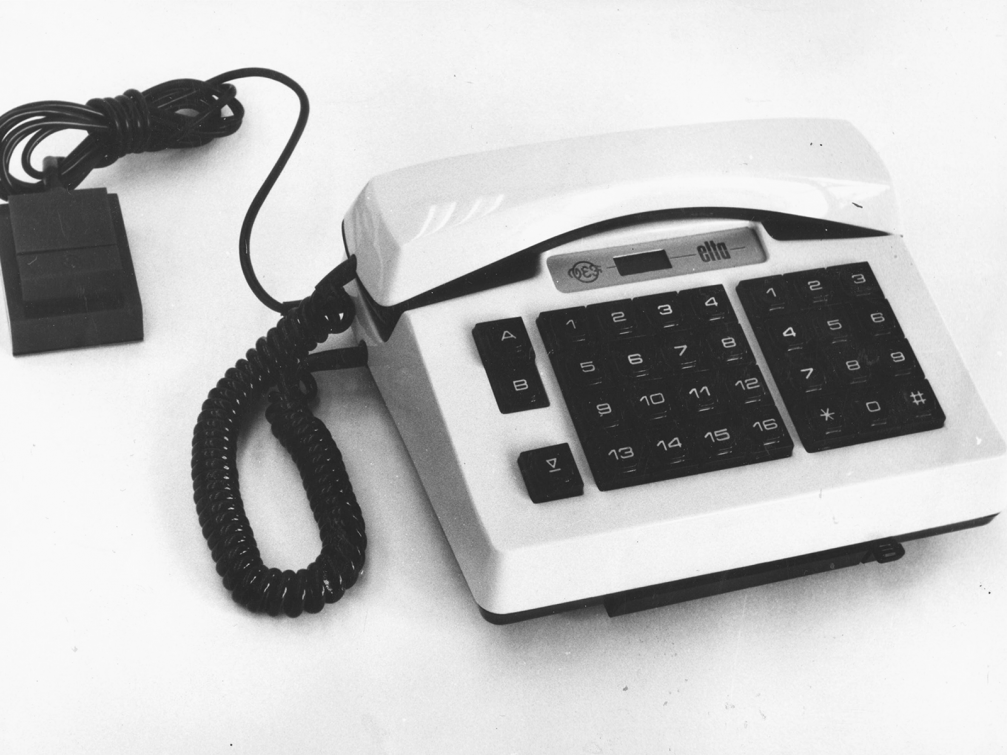

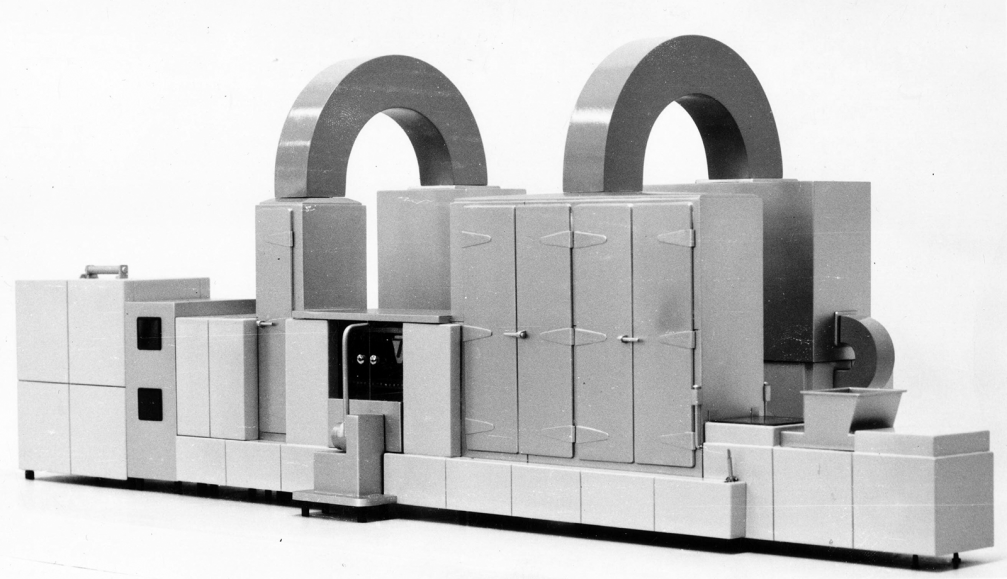

Motorcycles were the field Glūdiņš was best known for, but his portfolio also includes the mentioned «Spārīte» tricycle, skateboards, radio sets, a telephone, and even a production line of dairy products, and police vehicle design we can still see on our streets.

Your best known works are motorised vehicles that were built by «Sarkanā Zvaigzne». What was the designer’s daily routine like at the plant?

It was an enormous battle. «Sarkanā Zvaigzne» began producing mopeds in 1961. When I began working there in 1969, rationalisers had already been there. They wanted everything to be made simply, quickly; thus it would take a completely different look. Metal usage norms were limited, hours to be spent on one product were limited, the pay was limited. I had to constantly fight for these norms to be increased: I had to go to the manager, and not only to him, because the top managers were in Moscow. I had to travel there in order to prove the little moped we’d brought along was a little heavier, it used more metal, but consequently it would look incomparably better.

There were technical and human errors, but the main problem was in the electronics which used to fault more than often. Similar situation with the second–grade production was at the VEF plant. The only thing the Russians were good at was military machinery. What was used for consumer products came from discarded military equipment. We would sell «adjusted» models, because the engines themselves were built in Siauliai. Unfortunately I must admit Lithuanians weren’t technically excellent. I don’t want to put them down, I myself was born on Lithuania, in Mažeikai, but the Soviet system was such that nearly half of the moped engines were faulty.

There were problems with plating; products had a lot of chromed and nickeled parts, so there were problems with wastewaters. There was a pool on the territory that was said to be meant for workers bathing, but in the end all it was used for was that the water could be rid of plating. However, there would live some carps which, of course, no one ate. This one time we got to fish them, but they wouldn’t bite.

Where did orders come from, the ideas to introduce new products?

Valdis Kleinbergs, the constructor, and I had various ideas how to diversify the production; we would not leave the manager or the head engineer alone. There were times when we got support, but many more models would never see the daylight.

All Soviet engine plants were subordinated to the Institute in Serpukhov; we too had most of our commissions from them. Serpukhov would pay big money for developing new products — several hundreds of thousands of roubles. We, the creatives, were given some 5,000 roubles to be shared among the mechanics, constructors and others. In addition to the salary we would get 100–200 roubles per product, so we tried to work more to earn more.

I personally used to take mopeds and radios for commission approval — the car was full of rattling and clattering parts. When there, one day was spent repairing everything so that it could be presented. Evaluation would take place — what did do and what didn’t. I had to know which work to defend and what to say, but I never gave bribes — that disgusts me.

Despite problems, technical issues and the low quality of the materials you nevertheless got such a high result design–wise.

That’s what you have your head for. When you really need something, you can always think something up.

How did your passion for technology begin?

I must have had at least some talent. My mom was very good at drawing. Father was a dairy farmer, but he had carpentry skills — he would make furniture for our home, among other things. No one would buy me toys when I was a kid, so I had to make them myself. Father had a workshop and tools I could try using, which helped a lot. I had all the Russian airplane models, biplanes, cars where one could see through the window how the steering wheel turns. I built a ship, took it to the river, but it would capsize — I had to put some weight underneath, make a propeller, so that it would go. Work maketh master.

Later I finished the Economy department of Riga Industrial Polytechnic. I have worked as a labourer for «Sovetskaya Latviya» («Советская Латвия») printing press — I would push carts with books; later I went to be a planner, a rate setter.

Then you came to the Art Academy.

Before the academy, I went to the trade union crafts studio to study under Eduards Jurķelis, the water–colourist. He was the one to say I should apply to the Metal Art Department. He felt I had technical thinking.

One of the first tasks in the academy was given by the composition teacher Tālivaldis Gaumigs. We were given sawn pieces of steel, shown examples, and everyone had to make three tools for treating plaster. When I showed mine, everyone’s jaws dropped — they were polished shiny, with a six–sided handle, so fine. They could be used for plaster, or even in dentistry.

In the metal department there was this technician, Burka, and Gaumigs suggested I became his assistant. Before that, at «Sarkanā Zvaigzne», I had worked briefly as a shift technician, a technologist, a puncher adjuster, but now it was difficult to combine the studies with the work at the plant, so I began working for the academy. In the beginning, the pay was symbolic, but after graduating I went on to teach parallel to working at the plant.

Upon graduating the academy, in 1969, I designed a sports motorcycle that «Sarkanā Zvaigzne» would produce in quite large numbers. Consequently, we established the Construction Bureau, the Sports Bureau, the New Technology Bureau, which would service motorsports and where many people worked who had their heart and soul in this sport; also many race drivers were there.

Were you yourself a fan of motorsports?

It grew on me, with time. I would go to races in Estonia, the Pirita track. But I can’t say it was in my blood. My father used to own a motorcycle, though — I travelled Latvia on it; once, I flew into a ditch and was neck–deep in water.

When we built a new vehicle at the plant, it would be a celebration for the whole department and the construction office — everyone would try riding it in the yard to see how it actually went. Also, before starting the production, in order to get all paperwork done, we had to organise test drives on various road surfaces. There were field trips on mountain roads in Georgia, but I didn’t take part in those. My task was to make the vehicle look good, and I would gradually build a reputation for my work.

What is the key to making a vehicle visually attractive?

The vehicle’s parts must be proportionate. To avoid cases like «Rīga–4», where the frame was so big and heavy that the rest disappeared. You can add anything to it, but nothing looks good. You have to have good materials, a colour ensemble. Often these are intuitive decisions. Covering parts are all crucial — it is hard to tell the most important. The saddle was one of the difficult things. It consisted of three parts: a metal or plastic underplate, latex or artificial leather covering, under which there could be foam, to impress an ornament and which would make it look more interesting. The saddles were made by «Somdaris», but they looked like a loaf, or a bag. I know how to sew artificial leather, how to make patterns, so in order for the moped to go to the fair, I would take them apart and sew them back anew.

So this meant investing a lot of handcraft into the design development?

To draw a picture is only part of the job — all you need is a little imagination. However, for a model to be alive and working, you have to talk to constructors, so that they make a version of a frame you can begin putting things on. I used plaster for mock–ups, piecing it together, measuring, to get from one form to next. Back then we had to make all by hand and by sight. It’s no easy matter. It’s worth a million.

For instance, in the States in the sixties and seventies automobile designers were mostly sculptors who would shape cars by hand, using templates. Of course, now it can be done on a computer, with some imagination. This is why I think the world is not going to hell, but is going to progress. In old times, it was impossible to make a sphere; it was extremely difficult to fixate its direction. That was the case both in European and American industries. That is why there were these funny American cars with big long backs where horizontal lines would dominate, with little plasticity. Now it’s the other way round — everything has plasticity.

Did you have an opportunity back then to follow Western trends in motor design?

From time to time, with the help of some people, we could get magazines, catalogues. In the eighties, when Communism loosened its grip, I was allowed to travel abroad for the first time — I went to Czechoslovakia; I attended annual bicycle and moped fairs in Cologne, where I could get so much catalogues I could barely carry them, and I did so to take them back to the plant, show others. Because of the ICSID and the fact I was on the Board of the Latvian SSR Designers’ Union, in 1989 I went to the World Design Fair in Nagoya — the things I saw there!

You mentioned the Designers Union — you are one of its founding members and the first president. What were your goals back then?

It was a naive folly. It was 1988; I’d hoped that with Western possibilities and an honest, hardworking people the industry would become very important in Latvia. My intention was to gather not so much the designers from the Artists Union, but those who worked in factories: they weren’t highly educated artists, but they had production experience, which, in my view, would fit this organisation. It also included then well–known photographers, constructors. People from all over the place came who wanted to make something new. The design fair in 1987 was very uplifting, directing; it seemed very, very soon we’re going to get out of that stagnation that ruled the USSR. I don’t want to get into politics, but design is very closely connected to economy, national development. It seemed the Designers Union was going to be an advanced organisation. I don’t say nothing happens there anymore, but Latvia has no real space for industrial design; the furniture design is the only thing that goes forward.

I’ve heard you gave your students serious, technically sophisticated tasks, so that they would get to understand the designer’s role as a serious and responsible craft.

Yes, when I started at the Academy, there was big demand for such projects; many came to do their graduation works with me. I could share my experience on industrial work, the questions of the division of labour, etc. No designer builds a moped or any other product from start to finish like a craftsman. There are constructors, engineers — everyone does their part. Students weren’t taught that, but I managed to explain that to a few.

In 1990s, when the economy went down, many lost interest in doing things properly, but to exmatriculate someone from the Academy and say they have submitted an underqualified project — that seemed unacceptable. Together with young designers we used to go to Jaunkalsnava to visit Aleksandrs Dembo where we would fly kites we’d built during the semester. Later no one was interested in making as little as a simple kite that would actually fly, although all you had to know was a little aerodynamics and how it worked. I still have a kite at home which I used to fly in Jūrmala and take it from one place to another; all you have to know is how to control it, so that it doesn’t land on people or in the sand.

Several of your vehicles were still produced in Latvia and abroad even after «Sarkanā Zvaigzne» closed. Like «Spārīte» tricycle, which is still in production today. Do you get your share of royalties from it?

In essence, «Spārīte» was an English children’s bike that Russians bought. We did, however, change the wheel ornament, the frame, made elegant steering handles, a new saddle; now it has been changed even more. All those patents have already expired — all it is now is just information about what it was, how it was made and what it looked like. The Latvian patent was valid for 5–6 years, and one had to pay to renew it.

Often, especially at VEF, the author’s certificate had to contain a lot more names — the constructors, heads of each department, administration personnel. They did this because usually the products that were built as industrial prototypes went on to be serially produced, and those who were involved would receive a certain amount of money. I was less interested in that.

What was important for you then?

It was important to receive the author’s certificate. There were successes and failures; sometimes ideas were better than the results. At the same time, much has been done, and I am satisfied with that. My motto is to work according to my conscience, as well as I can, to make my people and those who use it happy and content. That the work is done with honour. An honour to God.

The author likes to thank Edīte Bērziņa, assistant professor at the Academy of Art, for her help in preparing this article.

Viedokļi