Spring is around the corner, and very soon an unprecedented urban initiative will open its doors to residents of Riga — the currently unused territory of the former Sporta Pils (Sports Palace) will turn into city gardens and meadows accessible to the public.

Activities of Riga neighbourhood associations, temporary experiments in the urban environment, and the recently elected City Council all point to the fact that Riga is changing. Not only is it becoming more citizen-friendly and accessible, it is also offering more and more ways to participate in shaping the urban environment. «Riga is ready for what many say it’s not ready yet. We need to look for tools to organise citizens’ engagement, facilitate this process, and support their experiments and projects,» says Renāte Prancāne, author of the idea of the Gardens of Sporta Pils. Besides being a positive messenger of change, the project also has a huge potential to become a model for citizens’ self-initiatives in the future.

Emptiness as an opportunity

Renāte came up with the idea of city gardens during self-isolation while watching the adjacent unused area through her window: «The pandemic highlighted the need for a spacious, publicly accessible urban area, as the outdoors refreshes and is a healthier alternative to public indoor spaces. By using strategic planning, it can also become a tool for changing citizens’ awareness and feelings about their own city.» Started as a response of a local resident to the immediate environment, the project continues to cultivate local engagement. The demand for plots in the Gardens of Sporta Pils exceeds the offer, and preference is given to residents of local neighbourhoods and those who volunteered to clean up the area last autumn, thereby strengthening the link between the gardeners and the urban environment they create.

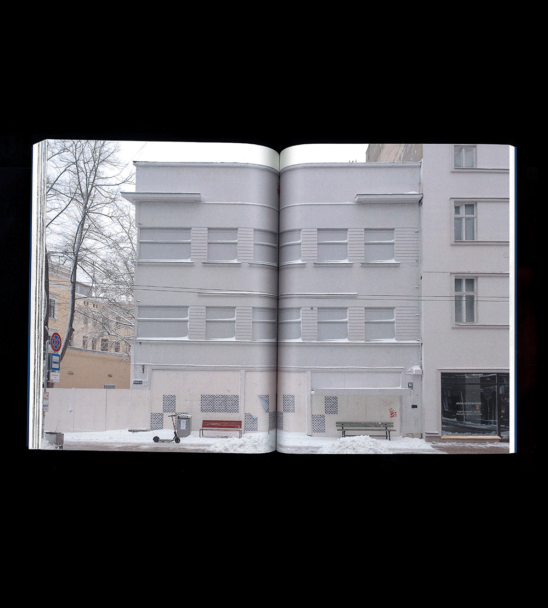

The area between Lielgabalu, Artilērijas, Barona and Tērbatas Street has been abandoned and closed off for over 13 years. The owner of the territory is the Estonian company Rotermann Square, whose plans to develop the area as a residential block were slowed down by the 2008 financial crisis. While the investor is preparing for construction works, they have agreed to permit temporary use of the site for a period of three years free of charge. The Gardens of Sporta Pils is one of the the first large-scale precedents in Riga when a private enterprise temporarily hands over its property to a public function. It also shows that the city lacks mechanisms to encourage the owners of abandoned, degraded areas to tidy them up and integrate them into a common urban fabric — albeit with temporary solutions. There are still many run-down and abandoned areas in Riga, and not only in Bolderāja and Andrejsala — such places can be found in the very centre of Riga.

Under the care of the Gardens of Sporta Pils team, the overgrown area of two hectares is transforming from nowhere into a place — publicly accessible meadows and gardens. Green recreation areas will be located in the hollow, where the Sporta Pils building once stood, while at the street level, which spans the perimeter of the block, 150 urban gardens will be available for community members. The area will also include public beds, cared for by the whole community, as well as compost sites, work zones and sharing points for gardening tools. A successful precedent for voluntary community engagement has been set by the community garden Audz in Sigulda launched by designer Nora Gavare two years ago.

Public space for everyone

The gardens can be rented for one season at democratic prices, making them available to a wide range of people. Accessibility permeates the entire project as a fundamental principle — ten of the gardens are available to people with special needs. One of the priority groups when looking for tenants for the gardens, is seniors. Too often, the older generation is left behind in contemporary urban design projects, but here the involvement of the elderly has already manifested in real life — quite a few seniors were seen in the volunteer groups that were cleaning up the territory last autumn. The visual identity and aesthetics of the gardens are also more accessible to a wider public than, say, Free Riga projects — by «accessible» meaning not dull or tasteless solutions, but the ability to visually address an audience outside of the hipster bubble. In addition to openness, timeliness, and sustainability, one of the fundamental values of the project is aesthetics — an environment that is beautiful, well-kept, and joyful.

The Gardens of Sporta Pils is a non-profit with a small budget — the project team works free of charge, and multiple sponsors are involved in the effort. The symbolic rent covers only a fraction of a season’s costs, but the community has been supporting the initiative through the crowd-funding platform Projektu Banka. The local government supports the project conceptually, however, not financially or in any other tangible form, mainly because there are currently no mechanisms to promote urban gardening. «There are cities with programs to help launch urban gardens, systems of support at a municipal level. I hope that we will be able to change policy-making in Riga too,» says Renāte.

Change of attitudes

Although the Gardens of Sporta Pils are in many ways a pioneer of community gardens in Riga, the tradition of small-scale gardening is old and widespread on the outskirts of the city. The allotment gardens of Lucavsala, Buļļu sala, Ziepniekkalns and other neighbourhoods are managed by a more marginal and less prosperous part of society that, fearing the future of their gardens, is in a state of slow, persistent conflict with the municipality. However, compared to the early 2000s, when the Riga City Council planned to eradicate all community gardens in the city, the government’s attitude towards the remaining gardens has improved significantly [1]. Of course, the cycle of cultivating and then pushing community gardens out of the city is closely linked to economic fluctuations and, perhaps, with the next real estate boom, the Council’s attitude will change again. But before it has happened here, perhaps we can hope that the Gardens of Sporta Pils will set a positive precedent and indirectly demonstrate that the small-scale gardens on the outskirts of Riga are not a burden, but rather places with a potential to become a meaningful, positive part of the city [2].

Unlike the traditional allotment gardens in Riga, the Gardens of Sporta Pils are more suitable for inexperienced, busy gardeners who may not have thought of having a garden before. Therefore, relatively small parcels are offered for rent — 12-square-metre lots where goods can be grown in raised beds. «We want to draw attention to urban gardening mostly as a tool for engaging the population — cutting down the road and showing that we can build a city on our own,» Renāte explains. Together with the creative team she has also worked on the Tērbatas Summer Street, which shares similar values. Renāte admits: «There’s hunger for more projects like this. And if you want to eat, you might as well make a sandwich not only for yourself, but for others, too.»

Vegetables, fruit, and democracy

One of Renāte’s sources of inspiration are the strong traditions of urban gardening in New York, where Renāte studied art history. The largest New York-based association of urban gardens currently runs more than 550 gardens across the city, handing over unused sites to groups of enthusiasts and local residents. This movement, which has now become a part of the city’s identity, also began with one small patch of land and one enthusiastic resident — at the zenith of the financial crisis of the 1970s, together with local volunteers Lisa Christy began to clean up and plant seeds in an abandoned site in Manhattan, until the municipality signed a contract with the community, starting a new urban gardening movement. The shift towards urban agriculture in other American and Western European cities is also closely linked to the economic crisis of the 1970s, but in Eastern Europe the main waves of urban garden developments took place in the interwar period and in the 1960s, which brought rapid industrialisation and migration from rural to urban areas. Both periods proved the need for alternative ways of providing urban dwellers with fresh produce. For example, the former allotment gardens of Skanste and Lucavsala flourished during the 1920–30s, providing more than 1600 families with fresh vegetables and fruit. Contrary to popular belief that urban gardens are inefficient, researchers of urban agriculture have estimated that even today 15 to 20% of all food is grown in urban allotment gardens [3].

Community gardens are a more recent phenomenon and, unlike allotment gardens, place more emphasis on social and cultural benefits rather than traditional garden goods. In addition to self-grown food, community gardens also provide recreational and educational opportunities. Given that gardening is a relatively accessible leisure activity with a potential for financial returns, community gardens contribute to uniting different groups of society. Self-determination, joint decision-making, direct engagement and co-operation in building a public environment cultivates a civic consciousness and faith in democratic processes. By reinforcing the principles of sustainability, green activism and degrowth, community gardens often highlight the shortcomings of neoliberal, profit-driven planning. Following the best examples of New York’s urban gardening projects, the Gardens of Sporta Pils also plans a cultural and arts programme, offers masterclasses, organises community activities, and cultivates community engagement and unity.

The team

The Gardens of Sporta Pils are created by a team of enthusiasts: director Renāte Prancāne, brand strategist Evija Krištopāne, landscape architect Ilze Rukšāne from the landscape design studio ALPS, architect Ansis Paeglītis from Teeja Arhitekti, landscape architect’s assistant Laima Daberte and community representatives Madara Rudzīte and Ieva Zandere. The project’s visual identity is created by Rūta Jumīte, illustrations are made by artist Estere Betija Grāvere.

Although it is no longer possible to rent a garden for this season, master classes are still open for everyone. Follow Sporta Pils Gardens on their Facebook page.

Footnotes

- The stark contrast between present and past attitudes towards allotment gardens is well illustrated by the director of the City Development Department of Riga City Council Vilnis Štrams, who gave an interview to Latvijas Vēstnesis in 2003, shortly before building the multifunctional hall Arēna Rīga. He urges Rigans to «become civilised» as in other «developed Western countries», asks for «anti-sanitary lairs» to be replaced by housing, financed by «cheap mortgages» and calls on the owners of allotment gardens to understand that cultural, recreational, entertainment or production facilities would be better placed in these areas. Now, when allotment gardens are included in the city’s Development Plan 2030, we start to realise that community gardens can become these aforementioned cultural, recreational, entertainment and even production sites, although they don’t bring direct profit.

- An insight into the parallel and not-so-gloomy life that takes place in the community gardens of Lucavsala is offered by the photo project Garden on the Island by Reinis Hofmanis.

- See, for instance, the book «Urban agriculture and food security, nutrition and health» by M. Armar-Klemesu.

Viedokļi