In her career as a designer, Rūta Jumīte has ventured far beyond the boundaries of function and form. She aspires to create meaningful changes that encompass not only various societal groups but even entire ecosystems. Rūta’s work on the visual identity of the youth organisation Young Folks, which received the National Design Award of Latvia 2023, allows even the club’s youngest members to become designers themselves. We had a conversation with Rūta about the role of a designer in shaping a sustainable future and the methods that broaden the perspective of design.

We’ve known you mainly as a graphic designer, but now you’re also involved in fields like system and environmental design. What prompted you to expand your scope of work?

I’ve been working in graphic design for about eight years, but alongside this practice, I’ve always had an interest in environmental and social sustainability, as well as design activism. These areas have been my passion and driving force. I graduated from Aalto University in Helsinki this spring, where I went a few years ago to study in the Master’s programme in Creative Sustainability. It provided me with various thinking tools and methods related to strategic design and encouraged me to think critically, reconsider my design practice, and broaden it.

How have the new methods you’ve learned influenced your creative process?

Before my studies in Helsinki, my process was often defined by the medium I was using. For example, in graphic design, it was a specific communication tool or strategy. Now, before choosing a specific medium, critical thinking kicks in. At Aalto University, I learned a strategic approach to systematic change. We are currently unable to align with nature, sustainably use natural resources, or ensure social sustainability and inclusivity. Hence, systemic change is necessary. My approach is to understand how, as a designer, I can promote these changes using acupuncture-like methods. Donella Meadows’ leverage point theory describes actions that can introduce systemic change into society. The most influential leverage point is changing beliefs and values, which is why I’m currently most interested in creating various workshops and educational contexts that provoke changes in thinking — how we design, how we relate to nature and each other, how we use resources, and what resources mean. Of course, shifting paradigms is the most challenging but also the most crucial aspect. If we can change beliefs, we can create better systems that follow suit.

You initiated the Design Summer School of the Art Academy of Latvia. Can you tell us more about it?

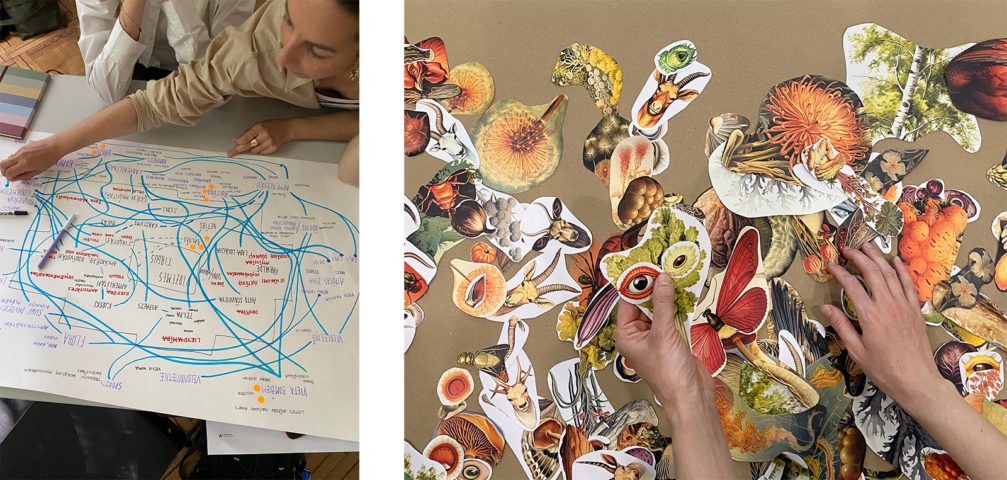

The school itself was an experiment, and we tried to combine various methods and involve guest lecturers who would help students create designs that include animals, plants, and environmental ecosystems. We dedicated the first week to research; designers often tend to rush to solutions very quickly, and this results in solutions that are often clichéd and don’t address problems at a deeper level. During the research phase, we aimed to introduce fresh perspectives and create new convictions, encouraging students to look at their values. Questions like who I’m designing for, who it’s important to, for humans, or maybe for some animals, should arise from the very beginning of the design process.

In service design, mapping methods are commonly used to understand stakeholders, their relationships, and the challenges to be addressed. We experimented by incorporating not only human stakeholder groups but also insects, birds, green areas, parks, wind, and rainwater into the process. In conventional human-centred practice, we might forget that humans are highly dependent on nature and other beings.

Through the Design School, you’ve taken the first steps to educate the next generation of designers. In your opinion, what could be the role of a designer in the future?

At Aalto University, we thought a lot about this, and we wrote countless essays on the topic. From this, I’ve concluded that the future role of a designer is to be a mediator, someone who connects various stakeholders and helps them communicate. In graphic design practice, I create communication design and act as a mediator between the one who wants to say something and the audience. But now I want to involve more parties in this communication process. I’m interested in how to connect designers and environmentalists, residents and other species, how to mediate such a process, and how to promote communication between all stakeholders. Scientists and designers often speak different languages and have different approaches. If a designer sees research as searching for a solution to a problem, scientists explore causality rather than finding solutions. I’m interested in creating a dialogue between parties with different perceptions. A designer as a mediator can also create unconventional contexts — they can involve someone whose opinion wouldn’t typically be heard in the process.

The involvement of various interested parties in the design process is increasingly discussed. How can this be done meaningfully?

Involvement comes at different levels, and it’s often added to the design process to merely check the box. Involvement and communication with the audience should happen at the very beginning of the project. An interesting example from our university was a project in which the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health asked us to create collaborative processes for people with disabilities. Our conclusion was that it would make the most sense to employ these people in as high a position as possible. The higher up the hierarchy the person who’s the subject of the design is, the more significant their influence is. It’s also crucial that there’s enough time to hear the opinions of the stakeholders and enough opportunities for meetings. To make people share their opinions, they need to feel safe. In a one-day workshop, people not accustomed to this type of work may not open up and feel creatively empowered. It’s essential to assess whether the involvement is fair to all stakeholders. If it’s cooperation with representatives of another species, it’s even more challenging.

Co-creation was a significant aspect in the creation of the visual identity of the youth organisation Young Folks. Can you tell us how this collaboration happened?

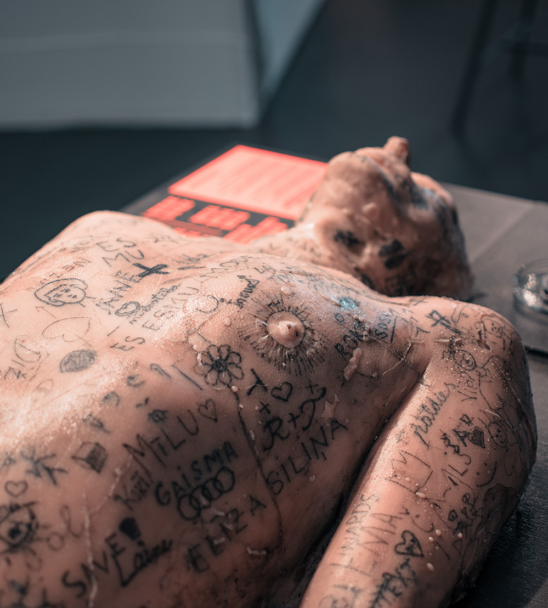

Young Folks creates the infrastructure for young people to establish their own clubs. Specific power positions, where one creates the environment and the other consumes it, are not established for them. Instead, young people are provided with tools and opportunities to implement what they consider important. I wanted to reflect this in the design as well. The process of creating the visual identity was very inspiring to me. I was surprised by how eager the young people were to get involved in this process, with some of them being particularly interested in graphic design.

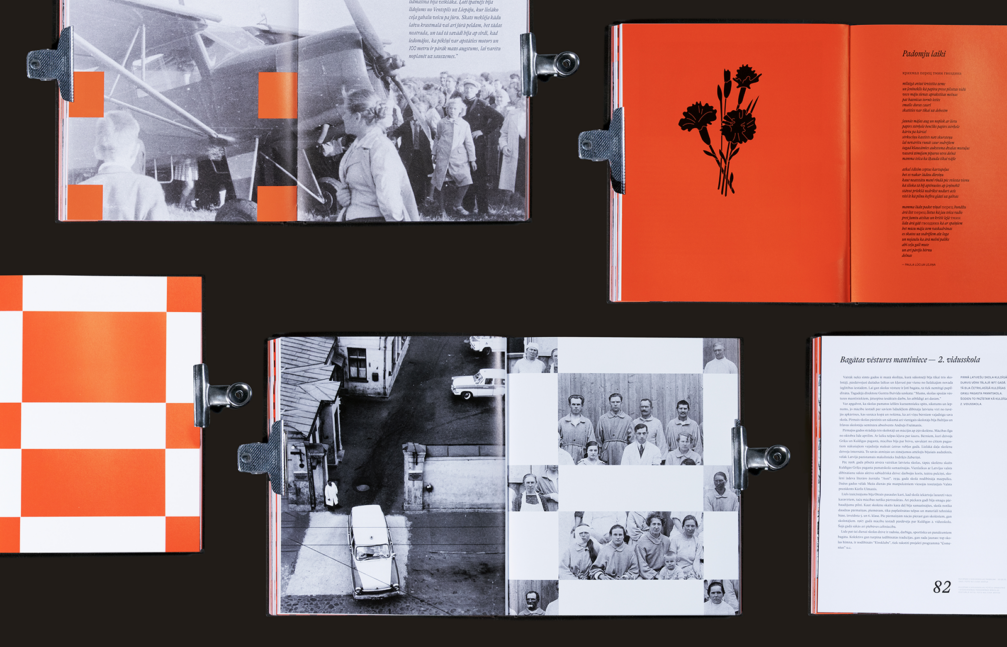

When creating a visual identity, a common problem often lies in not considering who will ultimately implement this identity. How did you manage to establish a system in which young people themselves become the designers?

In the classical approach, the designer hands over a brand book to the client, which contains all the rules. However, to work with such a book and create the necessary materials, a professional approach, hence a designer, is needed to continue the work. This can be a challenge for small organisations and companies. For instance, Young Folks has many needs — they have at least twenty subclubs, and each of them definitely won’t have its own designer. When I started working on the visual identity of Young Folks, I researched how they communicated on social media and identified graphic design tools such as text, illustrations, composition, and colour. If I created a visual material bank for them, the elements would quickly run out, so one of the key principles was that they could create the required illustrations themselves. Using the technique of collage, young people can cut something out of paper with scissors, which they then need to digitise, which is a more complex part. Cutting out an application can even be done by a small child, so this tool is available to everyone.

Next, I developed combinations of letters and colours that are simple but recognisable. All the elements are boldly placed together in large and small sizes. The overall style is unpredictable, there’s no specific grid or element placement. Such a free system suits their communication needs. Young people are also free, bold, and playful.

For this work, you received the National Design Award of Latvia 2023 in the Communication Design category, as well as the special award from FOLD. Why participate in design awards and competitions at all?

I think the value of such competitions lies within the designer community. They provide the opportunity to meet, discuss, and reflect on what you’ve accomplished. Awards show what we value and what is important to us. In the application form for the National Design Award of Latvia, I found very meaningful questions about sustainability and social impact. I liked that the competition had different categories, but I would like to expand this spectrum even further, including design for education and design for environmental and social sustainability.

You’ve worked as a researcher on food-related issues at Aalto University. Could you tell us more about that?

I’ve worked as a service designer for two years in a research group where we are jointly building an alternative economic system that promotes more sustainable food consumption. In collaboration with the largest student cafeteria chain in Helsinki, we created an experimental rewards system where students could earn tokens for sustainable choices. We’re researching if, by collecting points, it would be possible to create an alternative economic system. For example, in daily life, we encounter concepts like carbon footprint, which describes emissions, but there’s also a new concept: carbon handprint, which refers to emissions you’ve prevented through your actions. Rather than focusing on the negative, we can emphasise the positive. Through this experiment, we speculate that by recording points for sustainable choices, we could potentially provide tax deductions in the future.

Providing tangible benefits to people is definitely one way to change society’s mindset. How else can we foster a paradigm shift?

In my opinion, there’s great importance in the ability to cooperate by creating communities where resources can be shared. For example, maybe not everyone needs a personal car. Several families could use one. This might seem like a compromise in terms of convenience, but by sharing, we gain new friendships and relationships. You can also share your skills and knowledge. Perhaps someone in the community can repair one thing while another can fix something else.

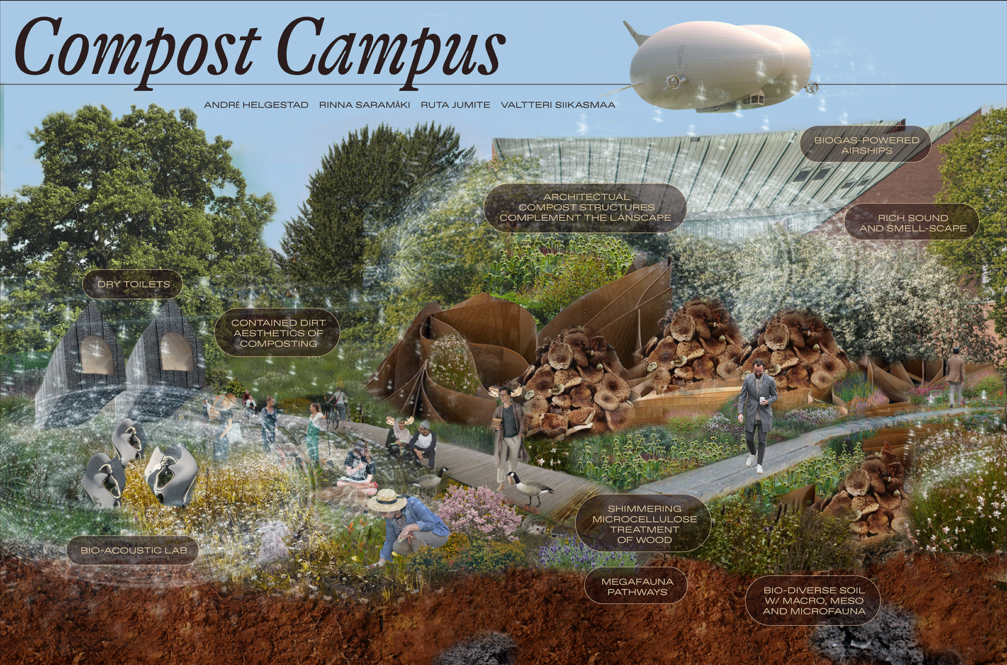

A significant factor in which a designer can get involved is changing society’s perception of aesthetics. What is a beautiful, organised city from a visual perspective? What is an attractive environment, interior, and clothing? How can we incorporate reused materials, solar panels, or composting into our designs? By changing aesthetics, we can help change habits.

You can follow Rūta’s creative work on her website and Instagram page.

Viedokļi